The Beauty Of Webb Telescope’s Mirrors

The Beauty of Webb Telescope’s Mirrors

The James Webb Space Telescope’s gold-plated, beryllium mirrors are beautiful feats of engineering. From the 18 hexagonal primary mirror segments, to the perfectly circular secondary mirror, and even the slightly trapezoidal tertiary mirror and the intricate fine-steering mirror, each reflector went through a rigorous refinement process before it was ready to mount on the telescope. This flawless formation process was critical for Webb, which will use the mirrors to peer far back in time to capture the light from the first stars and galaxies.

The James Webb Space Telescope, or Webb, is our upcoming infrared space observatory, which will launch in 2019. It will spy the first luminous objects that formed in the universe and shed light on how galaxies evolve, how stars and planetary systems are born, and how life could form on other planets.

A polish and shine that would make your car jealous

All of the Webb telescope’s mirrors were polished to accuracies of approximately one millionth of an inch. The beryllium mirrors were polished at room temperature with slight imperfections, so as they change shape ever so slightly while cooling to their operating temperatures in space, they achieve their perfect shape for operations.

The Midas touch

Engineers used a process called vacuum vapor deposition to coat Webb’s mirrors with an ultra-thin layer of gold. Each mirror only required about 3 grams (about 0.11 ounces) of gold. It only took about a golf ball-sized amount of gold to paint the entire main mirror!

Before the deposition process began, engineers had to be absolutely sure the mirror surfaces were free from contaminants.

The engineers thoroughly wiped down each mirror, then checked it in low light conditions to ensure there was no residue on the surface.

Inside the vacuum deposition chamber, the tiny amount of gold is turned into a vapor and deposited to cover the entire surface of each mirror.

Primary, secondary, and tertiary mirrors, oh my!

Each of Webb’s primary mirror segments is hexagonally shaped. The entire 6.5-meter (21.3-foot) primary mirror is slightly curved (concave), so each approximately 1.3-meter (4.3-foot) piece has a slight curve to it.

Those curves repeat themselves among the segments, so there are only three different shapes — 6 of each type. In the image below, those different shapes are labeled as A, B, and C.

Webb’s perfectly circular secondary mirror captures light from the 18 primary mirror segments and relays those images to the telescope’s tertiary mirror.

The secondary mirror is convex, so the reflective surface bulges toward a light source. It looks much like a curved mirror that you see on the wall near the exit of a parking garage that lets motorists see around a corner.

Webb’s trapezoidal tertiary mirror captures light from the secondary mirror and relays it to the fine-steering mirror and science instruments. The tertiary mirror sits at the center of the telescope’s primary mirror. The tertiary mirror is the only fixed mirror in the system — all of the other mirrors align to it.

All of the mirrors working together will provide Webb with the most advanced infrared vision of any space observatory we’ve ever launched!

Who is the fairest of them all?

The beauty of Webb’s primary mirror was apparent as it rotated past a cleanroom observation window at our Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. If you look closely in the reflection, you will see none other than James Webb Space Telescope senior project scientist and Nobel Laureate John Mather!

Learn more about the James Webb Space Telescope HERE, or follow the mission on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

More Posts from Smparticle2 and Others

5 Cookie Pro Tips from TED-Ed (and Science)

1. Cookies are for everyone. But everyone has cookie preferences. When you slide that cookie tray into the oven, you’re setting off a series of chemical reactions that transform one substance - dough - into another - cookies! The better you understand ‘Cookie Chemistry’, the better equipped you will be to create the cookies you crave.

2. Lots goes on in that oven, but one of science’s tastiest reactions occurs at 310º. Maillard reactions result when proteins and sugars breakdown and rearrange themselves into ring like structures which reflect light in a way that gives foods their distinctive, rich brown color. As this reaction occurs, it produces a range of flavor and aroma compounds, which also react with each other forming even more complex tastes and smells.

3. The final reaction to take place inside your cookie is caramelization and it occurs at 356º. Caramelization is what happens when sugar molecules breakdown under high heat, forming the sweet, nutty and slightly bitter flavor compounds that define…caramel! So if your recipe calls for a 350º oven - caramelization will never happen.

So, if your ideal cookie is barely browned - 310º will do. But if you want a tanned, caramelized cookie, crank up the heat! Caramelization continues up to 390º degrees.

4. No need to check that oven like a fiend. You don’t even really need a kitchen timer - when you smell the nutty, toasty aromas of the Maillard reaction and caramelization, your cookies are ready!

5. Baking is chemistry, friends! That’s right - PURE. SCIENCE. Check carefully before altering those recipes - chances are some of those ingredients and quantities are there for a reason.

Curious what else happens in that oven? Check out the TED-Ed Lesson The chemistry of cookies - Stephanie Warren

Animation by Augenblick Studios

“Before a scene, she would be muttering deprecations under her breath and making small moans. According to Vivien, the situation was stupid, the dialogue was silly, nobody could possibly believe the whole scene. And then…she would walk into the scene and do such a magnificent job that everybody on the set would be cheering.” -David O. Selznick

Rabies Viruses Reveal Wiring in Transparent Brains

Scientists under the leadership of the University of Bonn have harnessed rabies viruses for assessing the connectivity of nerve cell transplants. Coupled with a green fluorescent protein, the viruses show where replacement cells engrafted into mouse brains have connected to the host neural network.

The research is in Nature Communications. (full open access)

The Landscapes and Skylines of Howl’s Moving Castle ハウルの動く城

Failing to find a single functioning stapler, the grad student struggles to keep things together.

A research group at MIT has created a new class of fast-acting, soft robots from hydrogels. The robots are activated by pumping water in or out of hollow, interlocking chambers; depending on the configuration, this can curl or stretch parts of the robot. The hydrogel bots can move quickly enough to catch and release a live fish without harming it. (Which is a feat of speed I can’t even manage.) Because hydrogels are polymer gels consisting primarily of water, the robots could be especially helpful in biomedical applications, where their components may be less likely to be rejected by the body. For more, see MIT News or the original paper. (Image credit: H. Yuk/MIT News, source; research credit: H. Yuk et al.)

Dead Poets Society (1989)

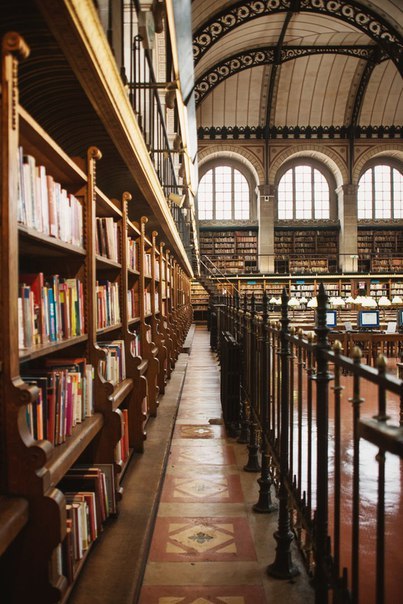

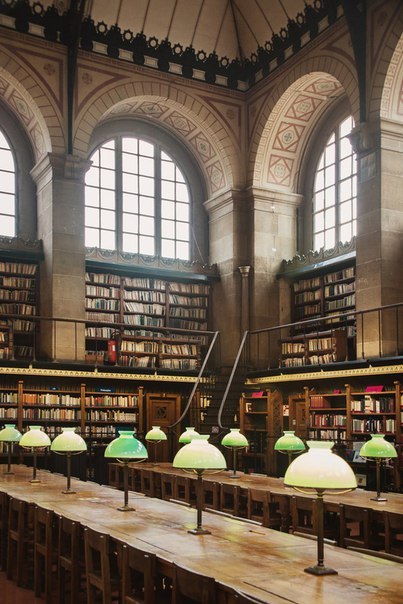

Sainte-Geneviève Library. Paris, France.

David Silverman @tubatron

1st appearance of Milhouse in 1st Butterfinger storyboard 11/18/1988 (missed the anni thing by a few weeks – )

Hold a buoyant sphere like a ping pong ball underwater and let it go, and you’ll find that the ball pops up out of the water. Intuitively, you would think that letting the ball go from a lower depth would make it pop up higher – after all, it has a greater distance to accelerate over, right? But it turns out that the highest jumps comes from balls that rise the shortest distance. When released at greater depths, the buoyant sphere follows a path that swerves from side to side. This oscillating path is the result of vortices being shed off the ball, first on one side and then the other. (Image and research credit: T. Truscott et al.)

-

redskytag liked this · 4 years ago

redskytag liked this · 4 years ago -

titaniumworld liked this · 4 years ago

titaniumworld liked this · 4 years ago -

maisdahilcorny reblogged this · 5 years ago

maisdahilcorny reblogged this · 5 years ago -

maisdahilcorny liked this · 5 years ago

maisdahilcorny liked this · 5 years ago -

marvelblog123 liked this · 5 years ago

marvelblog123 liked this · 5 years ago -

louiveee liked this · 5 years ago

louiveee liked this · 5 years ago