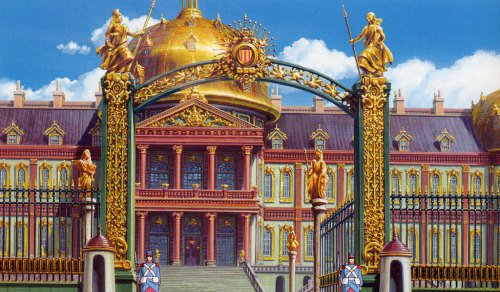

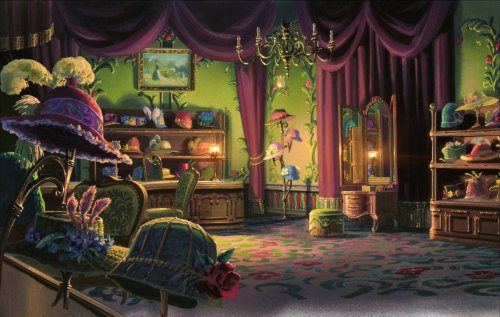

Howl’s Moving Castle, 2004

Howl’s Moving Castle, 2004

More Posts from Smparticle2 and Others

How we determine who’s to blame

How do people assign a cause to events they witness? Some philosophers have suggested that people determine responsibility for a particular outcome by imagining what would have happened if a suspected cause had not intervened.

This kind of reasoning, known as counterfactual simulation, is believed to occur in many situations. For example, soccer referees deciding whether a player should be credited with an “own goal” — a goal accidentally scored for the opposing team — must try to determine what would have happened had the player not touched the ball.

This process can be conscious, as in the soccer example, or unconscious, so that we are not even aware we are doing it. Using technology that tracks eye movements, cognitive scientists at MIT have now obtained the first direct evidence that people unconsciously use counterfactual simulation to imagine how a situation could have played out differently.

“This is the first time that we or anybody have been able to see those simulations happening online, to count how many a person is making, and show the correlation between those simulations and their judgments,” says Josh Tenenbaum, a professor in MIT’s Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, a member of MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, and the senior author of the new study.

Tobias Gerstenberg, a postdoc at MIT who will be joining Stanford’s Psychology Department as an assistant professor next year, is the lead author of the paper, which appears in the Oct. 17 issue of Psychological Science. Other authors of the paper are MIT postdoc Matthew Peterson, Stanford University Associate Professor Noah Goodman, and University College London Professor David Lagnado.

Follow the ball

Until now, studies of counterfactual simulation could only use reports from people describing how they made judgments about responsibility, which offered only indirect evidence of how their minds were working.

Gerstenberg, Tenenbaum, and their colleagues set out to find more direct evidence by tracking people’s eye movements as they watched two billiard balls collide. The researchers created 18 videos showing different possible outcomes of the collisions. In some cases, the collision knocked one of the balls through a gate; in others, it prevented the ball from doing so.

Before watching the videos, some participants were told that they would be asked to rate how strongly they agreed with statements related to ball A’s effect on ball B, such as, “Ball A caused ball B to go through the gate.” Other participants were asked simply what the outcome of the collision was.

As the subjects watched the videos, the researchers were able to track their eye movements using an infrared light that reflects off the pupil and reveals where the eye is looking. This allowed the researchers, for the first time, to gain a window into how the mind imagines possible outcomes that did not occur.

“What’s really cool about eye tracking is it lets you see things that you’re not consciously aware of,” Tenenbaum says. “When psychologists and philosophers have proposed the idea of counterfactual simulation, they haven’t necessarily meant that you do this consciously. It’s something going on behind the surface, and eye tracking is able to reveal that.”

The researchers found that when participants were asked questions about ball A’s effect on the path of ball B, their eyes followed the course that ball B would have taken had ball A not interfered. Furthermore, the more uncertainty there was as to whether ball A had an effect on the outcome, the more often participants looked toward ball B’s imaginary trajectory.

“It’s in the close cases where you see the most counterfactual looks. They’re using those looks to resolve the uncertainty,” Tenenbaum says.

Participants who were asked only what the actual outcome had been did not perform the same eye movements along ball B’s alternative pathway.

“The idea that causality is based on counterfactual thinking is an idea that has been around for a long time, but direct evidence is largely lacking,” says Phillip Wolff, an associate professor of psychology at Emory University, who was not involved in the research. “This study offers more direct evidence for that view.”

(Image caption: In this video, two participants’ eye-movements are tracked while they watch a video clip. The blue dot indicates where each participant is looking on the screen. The participant on the left was asked to judge whether they thought that ball B went through the middle of the gate. Participants asked this question mostly looked at the balls and tried to predict where ball B would go. The participant on the right was asked to judge whether ball A caused ball B to go through the gate. Participants asked this question tried to simulate where ball B would have gone if ball A hadn’t been present in the scene. Credit: Tobias Gerstenberg)

How people think

The researchers are now using this approach to study more complex situations in which people use counterfactual simulation to make judgments of causality.

“We think this process of counterfactual simulation is really pervasive,” Gerstenberg says. “In many cases it may not be supported by eye movements, because there are many kinds of abstract counterfactual thinking that we just do in our mind. But the billiard-ball collisions lead to a particular kind of counterfactual simulation where we can see it.”

One example the researchers are studying is the following: Imagine ball C is headed for the gate, while balls A and B each head toward C. Either one could knock C off course, but A gets there first. Is B off the hook, or should it still bear some responsibility for the outcome?

“Part of what we are trying to do with this work is get a little bit more clarity on how people deal with these complex cases. In an ideal world, the work we’re doing can inform the notions of causality that are used in the law,” Gerstenberg says. “There is quite a bit of interaction between computer science, psychology, and legal science. We’re all in the same game of trying to understand how people think about causation.”

Katie - Champ de Mars, Paris

Follow the Ballerina Project on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, Twitter & Pinterest

For information on purchasing Ballerina Project limited edition prints.

Finding Your Way Around in an Uncertain World

Suppose you woke up in your bedroom with the lights off and wanted to get out. While heading toward the door with your arms out, you would predict the distance to the door based on your memory of your bedroom and the steps you have already made. If you touch a wall or furniture, you would refine the prediction. This is an example of how important it is to supplement limited sensory input with your own actions to grasp the situation. How the brain comprehends such a complex cognitive function is an important topic of neuroscience.

Dealing with limited sensory input is also a ubiquitous issue in engineering. A car navigation system, for example, can predict the current position of the car based on the rotation of the wheels even when a GPS signal is missing or distorted in a tunnel or under skyscrapers. As soon as the clean GPS signal becomes available, the navigation system refines and updates its position estimate. Such iteration of prediction and update is described by a theory called “dynamic Bayesian inference.”

In a collaboration of the Neural Computation Unit and the Optical Neuroimaging Unit at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST), Dr. Akihiro Funamizu, Prof. Bernd Kuhn, and Prof. Kenji Doya analyzed the brain activity of mice approaching a target under interrupted sensory inputs. This research is supported by the MEXT Kakenhi Project on “Prediction and Decision Making” and the results were published online in Nature Neuroscience on September 19th, 2016.

The team performed surgeries in which a small hole was made in the skulls of mice and a glass cover slip was implanted onto each of their brains over the parietal cortex. Additionally, a small metal headplate was attached in order to keep the head still under a microscope. The cover slip acted as a window through which researchers could record the activities of hundreds of neurons using a calcium-sensitive fluorescent protein that was specifically expressed in neurons in the cerebral cortex. Upon excitation of a neuron, calcium flows into the cell, which causes a change in fluorescence of the protein. The team used a method called two-photon microscopy to monitor the change in fluorescence from the neurons at different depths of the cortical circuit (Figure 1).

(Figure 1: Parietal Cortex. A depiction of the location of the parietal cortex in a mouse brain can be seen on the left. On the right, neurons in the parietal cortex are imaged using two-photon microscopy)

The research team built a virtual reality system in which a mouse can be made to believe it was walking around freely, but in reality, it was fixed under a microscope. This system included an air-floated Styrofoam ball on which the mouse can walk and a sound system that can emit sounds to simulate movement towards or past a sound source (Figure 2).

(Figure 2: Acoustic Virtual Reality System. Twelve speakers are placed around the mouse. The speakers generate sound based on the movement of the mouse running on the spherical treadmill (left). When the mouse reaches the virtual sound source it will get a droplet of sugar water as a reward)

An experimental trial starts with a sound source simulating a distance from 67 to 134 cm in front of and 25 cm to the left of the mouse. As the mouse steps forward and rotates the ball, the sound is adjusted to mimic the mouse approaching the source by increasing the volume and shifting in direction. When the mouse reaches just by the side of the sound source, drops of sugar water come out from a tube in front of the mouse as a reward for reaching the goal. After the mice learn that they will be rewarded at the goal position, they increase licking the tube as they come closer to the goal position, in expectation of the sugar water.

The team then tested what happens if the sound is removed for certain simulated distances in segments of about 20 cm. Even when the sound is not given, the mice increase licking as they came closer to the goal position in anticipation of the reward (Figure 3). This means that the mice predicted the goal distance based on their own movement, just like the dynamic Bayesian filter of a car navigation system predicts a car’s location by rotation of tires in a tunnel. Many neurons changed their activities depending on the distance to the target, and interestingly, many of them maintained their activities even when the sound was turned off. Additionally, when the team injects a drug that suppresses neural activities in a region of the mice’s brains, called the parietal cortex they find that the mice did not increase licking when the sound is omitted. This suggests that the parietal cortex plays a role in predicting the goal position.

(Figure 3: Estimation of the goal distance without sound. Mice are eager to find the virtual sound source to get the sugar water reward. When the mice get closer to the goal, they increase licking in expectation of the sugar water reward. They increased licking when the sound is on but also when the sound is omitted. This result suggests that mice estimate the goal distance by taking their own movement into account)

In order to further explore what the activity of these neurons represents, the team applied a probabilistic neural decoding method. Each neuron is observed for over 150 trials of the experiment and its probability of becoming active at different distances to the goal could be identified. This method allowed the team to estimate each mouse’s distance to the goal from the recorded activities of about 50 neurons at each moment. Remarkably, the neurons in the parietal cortex predict the change in the goal distance due to the mouse’s movement even in the segments where sound feedback was omitted (Figure 4). When the sound was given, the predicted distance from the sound became more accurate. These results show that the parietal cortex predicts the distance to the goal due to the mouse’s own movements even when sensory inputs are missing and updates the prediction when sensory inputs are available, in the same form as dynamic Bayesian inference.

(Figure 4: Distance estimation in the parietal cortex utilizes dynamic Bayesian inference. Probabilistic neural decoding allows for the estimation of the goal distance from neuronal activity imaged from the parietal cortex. Neurons could predict the goal distance even during sound omissions. The prediction became more accurate when sound was given. These results suggest that the parietal cortex predicts the goal distance from movement and updates the prediction with sensory inputs, in the same way as dynamic Bayesian inference)

The hypothesis that the neural circuit of the cerebral cortex realizes dynamic Bayesian inference has been proposed before, but this is the first experimental evidence showing that a region of the cerebral cortex realizes dynamic Bayesian inference using action information. In dynamic Bayesian inference, the brain predicts the present state of the world based on past sensory inputs and motor actions. “This may be the basic form of mental simulation,” Prof. Doya says. Mental simulation is the fundamental process for action planning, decision making, thought and language. Prof. Doya’s team has also shown that a neural circuit including the parietal cortex was activated when human subjects performed mental simulation in a functional MRI scanner. The research team aims to further analyze those data to obtain the whole picture of the mechanism of mental simulation.

Understanding the neural mechanism of mental simulation gives an answer to the fundamental question of “How are thoughts formed?” It should also contribute to our understanding of the causes of psychiatric disorders caused by flawed mental simulation, such as schizophrenia, depression, and autism. Moreover, by understanding the computational mechanisms of the brain, it may become possible to design robots and programs that think like the brain does. This research contributes to the overall understanding of how the brain allows us to function.

Fluid systems can sometimes serve as analogs for other physical phenomena. For example, bouncing droplets can recreate quantum effects and a hydraulic jump can act like a white hole. In this work, a bathtub vortex serves as an analog for a rotating black hole, a system that’s extremely difficult to study under normal circumstances. In theory, the property of superradiance makes it possible for gravitational waves to extract energy from a rotating black hole, but this has not yet been observed. A recent study has, however, observed superradiance for the first time in this fluid analog.

To do this, the researchers set up a vortex draining in the center of a tank. (Water was added back at the edges to keep the depth constant.) This served as their rotating black hole. Then they generated waves from one side of the tank and observed how those waves scattered off the vortex. The pattern you see on the water surface in the top image is part of a technique used to measure the 3D surface of the water in detail, which allowed the researchers to measure incoming and scattered waves around the vortex. For superradiance to occur, scattered waves had to be more energetic after interacting with the vortex than they were before, which is exactly what the researchers found. Now that they’ve observed superradiance in the laboratory, scientists hope to probe the process in greater detail, which will hopefully help them observe it in nature as well. For more on the experimental set-up, see Sixty Symbols, Tech Insider UK, and the original paper. (Image credit: Sixty Symbols, source; research credit: T. Torres et al., pdf; via Tech Insider UK)

Yerres, Path Through the Old Growth Woods in the Park via Gustave Caillebotte

Size: 43x31 cm Medium: oil on canvas

From the TV series “The life of Mammals”.

(The Telegraph)

-

chocolunee liked this · 1 month ago

chocolunee liked this · 1 month ago -

flowerandi liked this · 5 months ago

flowerandi liked this · 5 months ago -

paopuofhearts liked this · 7 months ago

paopuofhearts liked this · 7 months ago -

felis-aquis reblogged this · 7 months ago

felis-aquis reblogged this · 7 months ago -

felis-aquis liked this · 7 months ago

felis-aquis liked this · 7 months ago -

library--fairy reblogged this · 7 months ago

library--fairy reblogged this · 7 months ago -

library--fairy liked this · 7 months ago

library--fairy liked this · 7 months ago -

sladez reblogged this · 7 months ago

sladez reblogged this · 7 months ago -

clickwitch reblogged this · 7 months ago

clickwitch reblogged this · 7 months ago -

rawrmemoirs reblogged this · 7 months ago

rawrmemoirs reblogged this · 7 months ago -

smithytw4666 liked this · 7 months ago

smithytw4666 liked this · 7 months ago -

everyfandom-girl reblogged this · 7 months ago

everyfandom-girl reblogged this · 7 months ago -

rawrbox liked this · 7 months ago

rawrbox liked this · 7 months ago -

oleksa24 liked this · 8 months ago

oleksa24 liked this · 8 months ago -

lightningcritter liked this · 8 months ago

lightningcritter liked this · 8 months ago -

lraptor liked this · 8 months ago

lraptor liked this · 8 months ago -

byuluno reblogged this · 8 months ago

byuluno reblogged this · 8 months ago -

smittenseraphim reblogged this · 8 months ago

smittenseraphim reblogged this · 8 months ago -

cleardreamersuitcaseknight liked this · 9 months ago

cleardreamersuitcaseknight liked this · 9 months ago -

chryso-poeia reblogged this · 9 months ago

chryso-poeia reblogged this · 9 months ago -

chryso-poeia liked this · 9 months ago

chryso-poeia liked this · 9 months ago -

hanbinbf liked this · 1 year ago

hanbinbf liked this · 1 year ago -

astro-moved reblogged this · 1 year ago

astro-moved reblogged this · 1 year ago -

chaboneobaiarroyoallende liked this · 1 year ago

chaboneobaiarroyoallende liked this · 1 year ago -

christiancomputerstudent liked this · 1 year ago

christiancomputerstudent liked this · 1 year ago -

sircrowley liked this · 1 year ago

sircrowley liked this · 1 year ago -

emy-can-craft liked this · 1 year ago

emy-can-craft liked this · 1 year ago -

prettygordito reblogged this · 1 year ago

prettygordito reblogged this · 1 year ago -

mumunga liked this · 1 year ago

mumunga liked this · 1 year ago -

bigolbee reblogged this · 1 year ago

bigolbee reblogged this · 1 year ago -

cryptidcain reblogged this · 1 year ago

cryptidcain reblogged this · 1 year ago -

the-not-witch-time-forgot reblogged this · 1 year ago

the-not-witch-time-forgot reblogged this · 1 year ago