Irving Langmuir, Who Won The 1932 Nobel Prize For ‘Surface Chemistry’, Demonstrates How Dipping An

Irving Langmuir, who won the 1932 Nobel Prize for ‘Surface Chemistry’, demonstrates how dipping an oil-covered finger into water creates a film of oil, pushing floating particles of powder to the edge.

The same phenomenon can be used to power a paper boat with a little ‘fuel’ applied to the back: as the film expands over the water, the boat is is propelled forward:

With experiments like this he revealed that these films are just one molecule thick - a remarkable finding in relation to the size of molecules.

In the full archive film, Langmiur goes on to demonstrate proteins spreading in the same way, revealing the importance of molecular layering for structure.

First, he drops protein solution onto the surface, and it spreads out in a clear circle, with a jagged edge:

Add a little more oil on top, and a star shape appears:

By breaking it up further, he makes chunks of the film which behave like icebergs on water:

You can watch the full demonstrations, along with hours more classic science footage, in our archive.

More Posts from Smparticle2 and Others

Black phosphorus holds promise for the future of electronics

Discovered more than 100 years ago, black phosphorus was soon forgotten when there was no apparent use for it. In what may prove to be one of the great comeback stories of electrical engineering, it now stands to play a crucial role in the future of electronic and optoelectronic devices.

With a research team’s recent discovery, the material could possibly replace silicon as the primary material for electronics. The team’s research, led by Fengnian Xia, Yale’s Barton L. Weller Associate Professor in Engineering and Science, is published in the journal Nature Communications April 19.

With silicon as a semiconductor, the quest for ever-smaller electronic devices could soon reach its limit. With a thickness of just a few atomic layers, however, black phosphorus could usher in a new generation of smaller devices, flexible electronics, and faster transistors, say the researchers.

That’s due to two key properties. One is that black phosphorus has a higher mobility than silicon—that is, the speed at which it can carry an electrical charge. The other is that it has a bandgap, which gives a material the ability to act as a switch; it can turn on and off in the presence of an electric field and act as a semiconductor. Graphene, another material that has generated great interest in recent years, has a very high mobility, but it has no bandgap.

Read more.

First and last appearances.

The Art of Lying

To keep pain in check, count down

Diverse cognitive strategies affect our perception of pain. Studies by LMU neuroscientist Enrico Schulz and colleagues have linked the phenomenon to the coordinated activity of neural circuits located in different brain areas.

Is the heat still bearable, or should I take my hand off the hotplate? Before the brain can react appropriately to pain, it must evaluate and integrate sensory, cognitive and emotional factors that modulate the perception and processing of the sensation itself. This task requires the exchange of information between different regions of the brain. New studies have confirmed that there is a link between the subjective experience of pain and the relative levels of neural activity in functional structures in various sectors of the brain. However, these investigations have been carried out primarily in contexts in which the perception of pain was intensified either by emotional factors or by consciously focusing attention on the painful stimulus. Now, LMU neuroscientist Enrico Schulz, in collaboration with colleagues at the University of Oxford, has asked how cognitive strategies that affect one’s subjective perception of pain influence the patterns of neural activity in the brain.

In the study, 20 experimental subjects were exposed to a painful cold stimulus. They were asked to adopt one of three approaches to attenuating the pain: (a) counting down from 1000 in steps of 7, (b) thinking of something pleasant or beautiful, and (c) persuading themselves – by means of autosuggestion – that the stimulus was not really that bad. During the experimental sessions, the subjects were hooked up to a 7T magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanner to visualise the patterns of neural activity in the brain, which were later analysed in detail.

In order to assess the efficacy of the different coping strategies, participants were also asked to evaluate the subjective intensity of the pain on a scale of 0 to 100. The results revealed that the countdown strategy was the most effective of the three methods. “This task obviously requires such a high level of concentration that it distracts the subject’s attention significantly from the sensation of pain. In fact some of our subjects managed to reduce the perceived intensity of pain by 50%,” says Schulz. “One participant later reported that she had successfully adopted the strategy during the most painful phase of childbirth.”

In a previous paper published in the journal Cortex in 2019, the same team had already shown that all three strategies help to attenuate the perception of pain, and that each strategy evoked a different pattern of neural activity. In the new study, Schulz and his collaborators carried out a more detailed analysis of the MRI scans, for which they divided the brain into 360 regions. “Our aim was to determine which areas in the brain must work together in order to successfully reduce the perceived intensity of the pain,” Schulz explains. “Interestingly, no single region or network that is activated by all three strategies could be identified. Instead, under each experimental condition, neural circuits in different brain regions act in concert to varying extents.”

The attenuation of pain is clearly a highly complex process, which requires a cooperative response that involves many regions distributed throughout the brain. Analysis of the response to the countdown technique revealed close coordination between different parts of the insular cortex, among other patterns. The imaginal distraction method, i.e. calling something picturesque or otherwise pleasing to mind, works only when it evokes intensive flows of information between the frontal lobes. Since these structures are known to be important control centres in the brain, the authors believe that engagement of the imaginative faculty may require a greater degree of control, because the brain needs to search through more ‘compartments’ – to find the right memory traces, for instance. Comparatively speaking, counting backwards stepwise – even in such awkward steps – is likely to be a more highly constrained task. “To cope with pain, the brain makes use of a recipe that also works well in other contexts,” says Anne Stankewitz, a co-author of the new paper: “success depends on effective teamwork.” Her team now plans to test whether their latest results can be usefully applied to patients with chronic pain.

Mulan (1998)

For her performance in Gone with the Wind (1939), Hattie McDaniel won a Best Supporting Actress Oscar on February 29, 1940. She was the first African American to win an Academy Award.

Rabies Viruses Reveal Wiring in Transparent Brains

Scientists under the leadership of the University of Bonn have harnessed rabies viruses for assessing the connectivity of nerve cell transplants. Coupled with a green fluorescent protein, the viruses show where replacement cells engrafted into mouse brains have connected to the host neural network.

The research is in Nature Communications. (full open access)

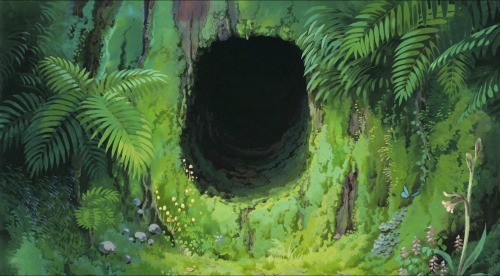

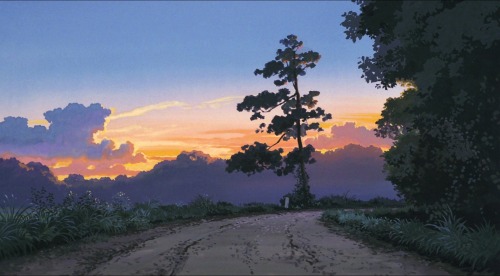

All these beautiful scenes and all I could think was "LOOK AT ALL THE SCATTERING" :')

More Art of My Neighbor Totoro - Art Direction by Kazuo Oga (1988)

Wanting to feel productive, the grad student prints multiple articles with reckless abandon.

-

super-lovely-collection liked this · 3 years ago

super-lovely-collection liked this · 3 years ago -

delightsofademigodess reblogged this · 3 years ago

delightsofademigodess reblogged this · 3 years ago -

invecepensi liked this · 4 years ago

invecepensi liked this · 4 years ago -

hvit-fjaer reblogged this · 6 years ago

hvit-fjaer reblogged this · 6 years ago -

livinginthe20s-blog1 reblogged this · 6 years ago

livinginthe20s-blog1 reblogged this · 6 years ago -

abhor1244 liked this · 6 years ago

abhor1244 liked this · 6 years ago -

woos-sweaterpaws liked this · 6 years ago

woos-sweaterpaws liked this · 6 years ago -

maiden-of-wolves reblogged this · 6 years ago

maiden-of-wolves reblogged this · 6 years ago -

jairos liked this · 7 years ago

jairos liked this · 7 years ago -

dkwpaint reblogged this · 7 years ago

dkwpaint reblogged this · 7 years ago -

coupatroupa reblogged this · 7 years ago

coupatroupa reblogged this · 7 years ago -

mariatarp reblogged this · 7 years ago

mariatarp reblogged this · 7 years ago -

rastagotsoul reblogged this · 7 years ago

rastagotsoul reblogged this · 7 years ago -

rastagotsoul liked this · 7 years ago

rastagotsoul liked this · 7 years ago -

void-latte liked this · 7 years ago

void-latte liked this · 7 years ago -

enniu reblogged this · 7 years ago

enniu reblogged this · 7 years ago -

peaceblank liked this · 7 years ago

peaceblank liked this · 7 years ago -

fluxsci reblogged this · 7 years ago

fluxsci reblogged this · 7 years ago -

suspicious-mustache liked this · 7 years ago

suspicious-mustache liked this · 7 years ago -

ms-corcoran-blog reblogged this · 7 years ago

ms-corcoran-blog reblogged this · 7 years ago -

taymakesmecrazy reblogged this · 7 years ago

taymakesmecrazy reblogged this · 7 years ago -

shade-the-changinggirl reblogged this · 7 years ago

shade-the-changinggirl reblogged this · 7 years ago -

the-cloud-road liked this · 7 years ago

the-cloud-road liked this · 7 years ago -

underbluegaze reblogged this · 7 years ago

underbluegaze reblogged this · 7 years ago -

classica-1750 reblogged this · 7 years ago

classica-1750 reblogged this · 7 years ago -

classica-1750 liked this · 7 years ago

classica-1750 liked this · 7 years ago -

underbluegaze liked this · 7 years ago

underbluegaze liked this · 7 years ago -

ny6ng4r reblogged this · 7 years ago

ny6ng4r reblogged this · 7 years ago -

citrusandsalt reblogged this · 7 years ago

citrusandsalt reblogged this · 7 years ago -

astermacguffin liked this · 7 years ago

astermacguffin liked this · 7 years ago -

goask-alice-in-wanderlust reblogged this · 8 years ago

goask-alice-in-wanderlust reblogged this · 8 years ago -

zolpidemon reblogged this · 8 years ago

zolpidemon reblogged this · 8 years ago -

alfc77-blog liked this · 8 years ago

alfc77-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

samelnicomposer liked this · 8 years ago

samelnicomposer liked this · 8 years ago -

investyourlove1019 reblogged this · 8 years ago

investyourlove1019 reblogged this · 8 years ago