Warrior Of The Grassland - Anup Deodhar - The Comedy Wildlife.

Warrior of the grassland - Anup Deodhar - The Comedy Wildlife.

More Posts from Smparticle2 and Others

Untitled // Jake Chamseddine

How to Build a More Resilient Brain

Your executive control center has helped your mental health survive the pandemic thus far. Here’s how to strengthen it for the future.

A Lot has been written (including by this reporter) about the mental health toll of the pandemic, and for good reason. The latest numbers from the National Pulse Survey, a weekly mental health screen conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics and the U.S. Census Bureau, estimate that nearly 40% of Americans are currently experiencing symptoms of either anxiety or depression, a 50% increase over pre-pandemic times.

In some ways, though, it’s surprising that this number isn’t even higher given the stress, trauma, loss, and loneliness of the past year. The vast majority of people have spent the last 12 months locked inside their homes, terrified of catching a deadly virus, and trying not to kill their spouse, children, or roommates — in more ways than one. People living alone have marked births, deaths, graduations, and layoffs with no one to hug but our pillows. And yet the majority of Americans seem to have made it through with their mental health still intact. How?

If the root of much of the mental illness that’s emerged during the pandemic is unrelenting chronic stress, the opposite is also true: Resilience to trauma lies in the ability to adapt positively to stress.

“Resilience is really this ability to bounce back in the face of adversity,” says Steven Southwick, MD, an emeritus professor of psychiatry at Yale University. “From a biological standpoint, it’s the ability to modulate and hopefully constructively harness the stress response.”

In the brain, resilience means protecting against many stress-induced changes, particularly in regard to the size, activity, and connectivity of the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex — the brain’s fear, memory and mood, and executive control centers, respectively.

How does one prevent these neural changes? Some of it is genetic — gene variants affect the levels and activity of circulating stress hormones, as well as the hormones that counteract them. But perhaps more importantly, behavioral interventions can also build resilience and serve as a buffer against stress for those important brain systems.

“Resilience is not an on-off switch,” says Deborah Marin, MD, a professor of psychiatry and director of the Mount Sinai Center for Stress, Resilience, and Personal Growth, which was launched in 2020 to help health care workers cope with pandemic stress. “Some people may be born with more resilience, there may be some genetic component there, but there’s a lot of environmental interaction at play — everything from poverty, access to health care, education, community support.”

Southwick has been studying resilience for decades, interviewing countless combat veterans and other trauma survivors with and without post-traumatic stress disorder. Based on these conversations, he, along with collaborator Dennis Charney, MD, dean of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, developed a rubric of 10 behaviors and traits that contribute to people’s resilience.

“We and many others believe that a big part of resilience is knowing how to regulate the stress response,” Southwick says. “Resilience, in many ways, is a set of skills that can be learned, and pretty much any of us can, to some significant degree, learn these skills.”

Several of these skills, along with a few other strategies, are outlined below, but the basic premise is to engage in activities that strengthen your brain’s executive control center (the prefrontal cortex) so that it doesn’t get overrun by the brain’s fear and arousal center (the amygdala) during times of stress.

Optimism and cognitive flexibility

Negative emotions — fear, anger, disgust — prepare the body to fight or to flee through activation of the sympathetic nervous system, which narrows people’s focus and restricts our behaviors to those actions. Positive emotions, on the other hand, lower arousal levels, broaden attention, and increase creativity, which helps people be more flexible in their thoughts and behaviors.

While some people are naturally more optimistic than others, you can train yourself to think more positively through the skill of cognitive reappraisal. During times of stress, this means seeing a threat not as an insurmountable problem but as a challenge to be solved. For example, many people have tried to see the bright side of the extra time spent at home during the pandemic, viewing it as an opportunity to learn a new skill or pick an old hobby back up. It doesn’t change the outcome of the pandemic, but it does make the best of a bad situation. Instead of being bored at home and lamenting the loss of your social life, you might have learned a new language or started playing the guitar again now that you have more free time.

Southwick calls this type of reframing “realistic optimism.” “The realistic optimist basically has a future-oriented attitude and the belief that things will turn out okay,” he says. “The realistic optimist actually tends to see as much of the negative information that a more pessimistic person might, but they don’t remain focused or glued to this negative perception, and they have the ability to rapidly disengage, particularly from those negative perceptions that are not solvable. And they tend to be pretty darn good at turning their attention to solvable problems.”

This type of cognitive flexibility is associated with activity in the prefrontal cortex, and stronger executive control from the region, particularly over the threat response triggered by the amygdala, is important for not letting stress and anxiety run wild. Chronic stress can damage the connection between the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala, taking the brakes off of the brain’s alarm system and potentially leading to anxiety and PTSD. Having a stronger prefrontal network that can protect against this negative effect of chronic stress may help support resilience.

Meditation

Another resilience strategy that exercises the prefrontal cortex is meditation, which can largely be thought of as a practice of attention. Every time your mind wanders while you meditate, it requires cognitive control exerted by your prefrontal cortex to bring it back to focusing on your breath. And just like working out your biceps will make them stronger, so will working out a brain region in this way. Activate an area enough times, and your neurons start to wire new connections there, making the thought process more automatic.

“Our brain structure is changing from moment to moment. It’s much more plastic than we ever thought; it’s like a muscle, you can strengthen it or weaken it,” Southwick says. “It’s called ‘use-dependent neuroplasticity’ — the more I practice accurately, the more my brain will respond, and it will be less effortful in the future.”

On a more immediate time scale, taking a few deep breaths in a moment of stress can turn on the parasympathetic nervous system — the counterpart to the fight-or-flight response — and start to undo some of the body’s stress response. Deep breathing also lowers levels of noradrenaline, a brain chemical that increases arousal, which is also released in response to stress.

Stress inoculation and facing your fears

You can also train your brain to handle stress better through exposure to smaller stressors, particularly early in life. Scientists call this stress inoculation: Just like exposure to a tiny amount of a virus will educate your immune system on how to respond to it better next time, learning how to deal with mild stressors teaches your brain how to handle bigger stressors later.

“There’s some evidence that exposure to chronic stress early in life can actually make you resilient to stress later in life. Like that initial experience changes your resilience capacity,” says James Herman, PhD, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience at the University of Cincinnati and director of the Laboratory of Stress Neurobiology. “You have all of these stressors that are present all the time, but if you’re used to them, you become resilient to them. They can help you later on in life, and they might even be beneficial.”

Part of this process is facing your fears, which, again, involves the prefrontal cortex overcoming the alarm bells ringing from the amygdala.

“Fear is completely natural. It’s, in many ways, a signal or something that is warning us, it’s a guide,” Southwick says. “But if you allow fear to hang around too long, it might evolve into panic. And when someone’s panicked, there tends to be a flooding of noradrenaline to the prefrontal cortex, which has a tendency to take the prefrontal cortex offline, which means that I’m now operating much more via my amygdala because my prefrontal cortex is no longer inhibiting the amygdala to the same degree that it normally does.”

Practicing facing your fears in lower stakes situations teaches your brain how to maintain control during stressful scenarios so that fear doesn’t turn into panic and spiral out of control. This isn’t something you can magically do right now to help you deal with the rest of the pandemic, but as things quiet down, consider it to help build your resilience for the future. Maybe challenge yourself to sign up for a class you’ve been intimidated to take or speak up in a meeting if normally you stay silent. In clinical settings, facing your fears is called exposure therapy and is used to treat anxiety disorders, particularly phobias and PTSD. With it, you gradually build up your exposure to the thing you’re afraid of while practicing relaxation techniques to prevent your amygdala and sympathetic nervous system from running out of control. The goal is ultimately to desensitize yourself to your fear, but the therapy can help you learn how to remain calm in any stressful situation.

Exercise and sleep

Maintaining good physical health is also critical for your mental capabilities. If you’ve heard it once, you’ve heard it a million times: Exercise is one of the best things you can do for your brain. Physical activity helps the brain grow new connections between brain cells and maybe even new neurons themselves. Much of this growth takes place in, you guessed it, the prefrontal cortex, as well as in the hippocampus, an area involved in regulating mood and memory. The new growth can help offset the loss of connections that occurs in those regions with chronic stress. Exercise also boosts levels of the feel-good neurochemicals dopamine and serotonin, both of which are depleted in people with depression.

On the flip side, lack of sleep can exacerbate many of the problems seen in the brain with chronic stress. One study from 2019 showed that sleep deprivation can cause a decrease in activity in the prefrontal cortex, while the amygdala becomes more reactive after a poor night’s sleep. This shift in activity correlated with people’s feelings of anxiety.

Social support

A crucial resilience strengthener experts bring up again and again is social support. In many ways, social connection counters the stress response from the sympathetic nervous system. Being with a friend or family member, especially during a stressful situation, dampens the activity of noradrenaline and cortisol. It also activates the reward center of the brain, providing a boost in dopamine.

“Human beings have many, many sources of resilience, but I think the most important is our relationships and social support and the way that we can help each other,” says Ann Masten, PhD, a psychologist and professor of child development at the University of Minnesota. “Feelings of belonging and support are powerful protective factors for many different kinds of situations.”

This aspect of resilience can be tricky during a pandemic when physical distancing from people outside of your household is necessary for safety. However, just knowing you have people in your corner who love and support you‚ even if you can’t currently be with them, still has a protective effect.

“The perception that you have others you can count on, even if they’re not presently there, has been shown to buffer some of the physiological effects [of stress],” says Julianne Holt-Lunstad, PhD, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Brigham Young University. “[We’ve shown that] people who simply have more supportive people in their social network are less cardiovascularly reactive to a stressor task. Other studies have shown that even just thinking about someone who is very supportive is enough to buffer some of those physiological responses.”

Purpose and self-efficacy

Another key protective factor is having a sense of purpose and not feeling like you’re helpless in the stressful situation you’re facing. Similar to cognitive reappraisal, viewing the stressful scenario as an opportunity and that you have something to contribute provides a powerful sense of self-efficacy, which can prevent people from despairing. Scientists have known for decades that a feeling of helplessness is strongly tied to the development of depression, while having a sense of control is linked to resilience.

This factor is particularly relevant for frontline health care workers who have seen some of the greatest trauma during the pandemic. While roughly half of doctors, nurses, and other hospital staff are understandably experiencing depression, PTSD, and anxiety as a consequence, the other half have remained resilient. One reason may be because they can directly impact the course of the pandemic and have the ability to save people’s lives.

“Even if you’re working really hard, [if you’re] able to feel that your work has a sense of meaning and purpose, and that sense of meaning and purpose is aligned and shared by your colleagues and your institution, then you can tolerate an incredible amount of stress,” says Ronald Epstein, MD, a professor of family medicine at the University of Rochester Medical Center who has studied physician burnout.

If you’re not a frontline worker, it may be a little harder to feel like you have a role to play or any control over the situation. However, just because you can’t change the larger course of the pandemic doesn’t mean that you can’t take steps to control your own risk and the day-to-day unfolding of your life within it. Staying home for a year and forgoing social interactions and a normal life has been hard on everyone, but keep in mind that you’re doing it for a really important purpose — you’re potentially saving a life, maybe even your own. Every time you wear a mask, you’re taking your health into your own hands. Even just making and sticking to a daily schedule that slots in exercise or meditation can give you back some semblance of control.

“The pandemic and catastrophes like this can give you a sense that everything is out of control,” Masten says. “We don’t have a lot of control over what’s happening at a global level, but in our own lives, day by day, we can plan, take things one step at a time, and we can give ourselves a sense of accomplishment just in daily planning and setting manageable goals that provide us with a sense of self-efficacy.”

Preparation

Another reason that there isn’t more mental illness among health care workers is that they’ve trained for these types of situations. If someone was pulled off the street to work a day in the intensive care unit, their stress levels would go through the roof and they could very quickly become overwhelmed by the pressure and high stakes of the work, not to mention being exposed to so much suffering and death. But health care workers deal with this every day as part of their jobs.

Notably, many of the health care workers who did develop symptoms of depression or anxiety said that they had been transferred to a different department during the pandemic. In other words, they wound up doing a job that they had not been trained for. For example, nurses and doctors who normally work in rehabilitation were redeployed to the intensive care unit, where they saw much more death than they were used to. Some health care workers had to use ventilators for the first time since graduating from medical school, a skill they may not have felt as competent at.

“Redeployment was definitely a factor that contributed to having more symptomatology, either depression or anxiety or PTSD,” says Marin, the Mount Sinai psychiatrist who directs the Center for Stress, Resilience, and Personal Growth. “That probably is because when you’re redeployed, you’re doing a new skill set that you haven’t been doing or you’re used to, and you’re removed from an environment that may have your own community resilience.”

Virtually no one was prepared for the pandemic and all that it threw at us (how could you be?), and many people — and systems — broke down as a result. But there are at least lessons to be learned should disaster strike again in the future. Perhaps you still have a cache of beans and toilet paper stocked away that can give you a little peace of mind if there’s another stress on grocery store chains. Maybe you finally got to know your neighbors, and now you know who on your street might need a little more help getting groceries, or who has kids around the same age as yours. Or if your pandemic hobby was gardening or hiking or spending more time outdoors, maybe you developed some new survival or self-sufficiency skills you can keep in your back pocket to feel a little more competent and confident going forward.

Hopefully, government and institutions have also learned how to better support under-resourced groups, including parents, the elderly, and the unemployed. “I think this pandemic is a wake-up call for a lot of disasters that probably are going to come in the future, either other pandemics or climate disasters related to weather,” says Masten. “I think we need to think about how do we organize work and cities, and how do we support families with enough child care and financial support to give us flexibility?” These are big complicated questions, but many organizations, particularly those focused on public health, are starting to ask them, which is an important first step.

The past year has turned our lives upside down. People have lost loved ones, jobs, social lives, and any sense of normalcy. It’s entirely understandable, and even expected, that living through a year of a deadly pandemic would take a toll on mental health. But it’s also important to remember that depression, anxiety, and PTSD aren’t an inevitable result, although it does take some work to protect against them.

“As humans, we have this immense capacity to get through transient stresses,” Epstein says. “That’s why humans have survived — we’re not physically strong creatures, and we don’t have a lot of natural protection, so we rely on our ability to adapt to different circumstances.”

Epstein, who leads resilience workshops for health care workers, advises people to embed small habits into their day that can help relieve their stress, at least temporarily. This could be a five-minute meditation or breathing exercise when you feel yourself getting worked up; a quick walk around the block every day at lunch; a standing text or phone check-in with a friend; or a daily gratitude list you make at bedtime.

“Try to find something really, really small that you can do every day that will improve your own sense of positive potential, gratitude, community presence, your ability to be attentive — something that will actually make you feel a bit more aware and in control of your own inner life,” he says. “There’s a whole catalog of things that people can do that are awfully simple, easily accomplished, and doable, it’s just a question of reminding yourself and making that commitment.”

It’s also important to keep in mind that you don’t have to go through this alone. Again, social support is one of the most beneficial factors when it comes to resilience, so reach out to a friend or colleague if you’re struggling — they probably need to talk just as much as you do.

“Yes, we each can take actions, we each can be optimistic or practice meditation by ourselves to help deal with trauma. But a lot of the capacity for human resilience comes from the ways we interact with each other in relationships, in our friendships, in our congregating in cultural practices,” says Masten. “Human beings have a lot of capabilities to come up with ideas and share them of how to deal with whatever current issues are coming up with the pandemic or other kinds of struggles.”

She continues, “We’re great at ingenuity, and you can see […] as the challenges unfold, the mobilization unfolding at the same time. We respond when we’re challenged.”

By Dana G Smith Ph.D., (Medium). Illustration: Carolyn Figel

Spacewalk Recap Told in GIFs

Friday, Oct. 20, NASA astronauts Randy Bresnik and Joe Acaba ventured outside the International Space Station for a 6 hour and 49 minute spacewalk. Just like you make improvements to your home on Earth, astronauts living in space periodically go outside the space station to make updates on their orbiting home.

During this spacewalk, they did a lot! Here’s a recap of their day told in GIFs…

All spacewalks begin inside the space station. Astronauts Paolo Nespoli and Mark Vande Hei helped each spacewalker put on their suit, known as an Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU).

They then enter an airlock and regulate the pressure so that they can enter the vacuum of space safely. If they did not regulate the pressure safely, the astronauts could experience something referred to as “the bends” – similar to scuba divers.

Once the two astronauts exited the airlock and were outside the space station, they went to their respective work stations.

Bresnik replaced a failed fuse on the end of the Dextre robotic arm extension, which helps capture visiting vehicles.

During that time, Acaba set up a portable foot restraint to help him get in the right position to install a new camera.

While he was getting set up, he realized that there was unexpected wearing on one of his safety tethers. Astronauts have multiple safety mechanisms for spacewalking, including a “jet pack” on their spacesuit. That way, in the unlikely instance they become untethered from the station, the are able to propel back to safety.

Bresnik was a great teammate and brought Acaba a spare safety tether to use.

Once Acaba secured himself in the foot restraint that was attached to the end of the station’s robotic arm, he was maneuvered into place to install a new HD camera. Who was moving the arm? Astronauts inside the station were carefully moving it into place!

And, ta da! Below you can see one of the first views from the new enhanced HD camera…(sorry, not a GIF).

After Acaba installed the new HD camera, he repaired the camera system on the end of the robotic arm’s hand. This ensures that the hand can see the vehicles that it’s capturing.

Bresnik, completed all of his planned tasks and moved on to a few “get ahead” tasks. He first started removing extra thermal insulation straps around some spare pumps. This will allow easier access to these spare parts if and when they’re needed in the future.

He then worked to install a new handle on the outside of space station. That’s a space drill in the above GIF.

After Acaba finished working on the robotic arm’s camera, he began greasing bearings on the new latching end effector (the arm’s “hand”), which was just installed on Oct. 5.

The duo completed all planned spacewalk tasks, cleaned up their work stations and headed back to the station’s airlock.

Once safely inside the airlock and pressure was restored to the proper levels, the duo was greeted by the crew onboard.

They took images of their spacesuits to document any possible tears, rips or stains, and took them off.

Coverage ended at 2:36 p.m. EDT after 6 hours and 49 minutes. We hope the pair was able to grab some dinner and take a break!

You can watch the entire spacewalk HERE, or follow @Space_Station on Twitter and Instagram for regular updates on the orbiting laboratory.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

Making glass invisible: A nanoscience-based disappearing act

If you have ever watched television in anything but total darkness, used a computer while sitting underneath overhead lighting or near a window, or taken a photo outside on a sunny day with your smartphone, you have experienced a major nuisance of modern display screens: glare. Most of today’s electronics devices are equipped with glass or plastic covers for protection against dust, moisture, and other environmental contaminants, but light reflection from these surfaces can make information displayed on the screens difficult to see.

Now, scientists at the Center for Functional Nanomaterials (CFN) – a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility at Brookhaven National Laboratory – have demonstrated a method for reducing the surface reflections from glass surfaces to nearly zero by etching tiny nanoscale features into them.

Whenever light encounters an abrupt change in refractive index (how much a ray of light bends as it crosses from one material to another, such as between air and glass), a portion of the light is reflected. The nanoscale features have the effect of making the refractive index change gradually from that of air to that of glass, thereby avoiding reflections. The ultra-transparent nanotextured glass is antireflective over a broad wavelength range (the entire visible and near-infrared spectrum) and across a wide range of viewing angles. Reflections are reduced so much that the glass essentially becomes invisible.

Read more.

Directly Reprogramming a Cell's Identity with Gene Editing

Researchers have used CRISPR—a revolutionary new genetic engineering technique—to convert cells isolated from mouse connective tissue directly into neuronal cells.

In 2006, Shinya Yamanaka, a professor at the Institute for Frontier Medical Sciences at Kyoto University at the time, discovered how to revert adult connective tissue cells, called fibroblasts, back into immature stem cells that could differentiate into any cell type. These so-called induced pluripotent stem cells won Yamanaka the Nobel Prize in medicine just six years later for their promise in research and medicine.

Since then, researchers have discovered other ways to convert cells between different types. This is mostly done by introducing many extra copies of “master switch” genes that produce proteins that turn on entire genetic networks responsible for producing a particular cell type.

Now, researchers at Duke University have developed a strategy that avoids the need for the extra gene copies. Instead, a modification of the CRISPR genetic engineering technique is used to directly turn on the natural copies already present in the genome.

These early results indicate that the newly converted neuronal cells show a more complete and persistent conversion than the method where new genes are permanently added to the genome. These cells could be used for modeling neurological disorders, discovering new therapeutics, developing personalized medicines and, perhaps in the future, implementing cell therapy.

The study was published on August 11, 2016, in the journal Cell Stem Cell.

“This technique has many applications for science and medicine. For example, we might have a general idea of how most people’s neurons will respond to a drug, but we don’t know how your particular neurons with your particular genetics will respond,” said Charles Gersbach, the Rooney Family Associate Professor of Biomedical Engineering and director for the Center for Biomolecular and Tissue Engineering at Duke. “Taking biopsies of your brain to test your neurons is not an option. But if we could take a skin cell from your arm, turn it into a neuron, and then treat it with various drug combinations, we could determine an optimal personalized therapy.”

“The challenge is efficiently generating neurons that are stable and have a genetic programming that looks like your real neurons,” says Joshua Black, the graduate student in Gersbach’s lab who led the work. “That has been a major obstacle in this area.”

In the 1950s, Professor Conrad Waddington, a British developmental biologist who laid the foundations for developmental biology, suggested that immature stem cells differentiating into specific types of adult cells can be thought of as rolling down the side of a ridged mountain into one of many valleys. With each path a cell takes down a particular slope, its options for its final destination become more limited.

If you want to change that destination, one option is to push the cell vertically back up the mountain—that’s the idea behind reprogramming cells to be induced pluripotent stem cells. Another option is to push it horizontally up and over a hill and directly into another valley.

“If you have the ability to specifically turn on all the neuron genes, maybe you don’t have to go back up the hill,” said Gersbach.

Previous methods have accomplished this by introducing viruses that inject extra copies of genes to produce a large number of proteins called master transcription factors. Unique to each cell type, these proteins bind to thousands of places in the genome, turning on that cell type’s particular gene network. This method, however, has some drawbacks.

“Rather than using a virus to permanently introduce new copies of existing genes, it would be desirable to provide a temporary signal that changes the cell type in a stable way,” said Black. “However, doing so in an efficient manner might require making very specific changes to the genetic program of the cell.”

In the new study, Black, Gersbach, and colleagues used CRISPR to precisely activate the three genes that naturally produce the master transcription factors that control the neuronal gene network, rather than having a virus introduce extra copies of those genes.

CRISPR is a modified version of a bacterial defense system that targets and slices apart the DNA of familiar invading viruses. In this case, however, the system has been tweaked so that no slicing is involved. Instead, the machinery that identifies specific stretches of DNA has been left intact, and it has been hitched to a gene activator.

The CRISPR system was administered to mouse fibroblasts in the laboratory. The tests showed that, once activated by CRISPR, the three neuronal master transcription factor genes robustly activated neuronal genes. This caused the fibroblasts to conduct electrical signals—a hallmark of neuronal cells. And even after the CRISPR activators went away, the cells retained their neuronal properties.

“When blasting cells with master transcription factors made by viruses, it’s possible to make cells that behave like neurons,” said Gersbach. “But if they truly have become autonomously functioning neurons, then they shouldn’t require the continuous presence of that external stimulus.”

The experiments showed that the new CRISPR technique produced neuronal cells with an epigenetic program at the target genes matching the neuronal markings naturally found in mouse brain tissue.

“The method that introduces extra genetic copies with the virus produces a lot of the transcription factors, but very little is being made from the native copies of these genes,” explained Black. “In contrast, the CRISPR approach isn’t making as many transcription factors overall, but they’re all being produced from the normal chromosomal position, which is a powerful difference since they are stably activated. We’re flipping the epigenetic switch to convert cell types rather than driving them to do so synthetically.”

The next steps, according to Black, are to extend the method to human cells, raise the efficiency of the technique and try to clear other epigenetic hurdles so that it could be applied to model particular diseases.

“In the future, you can imagine making neurons and implanting them in the brain to treat Parkinson’s disease or other neurodegenerative conditions,” said Gersbach. “But even if we don’t get that far, you can do a lot with these in the lab to help develop better therapies.”

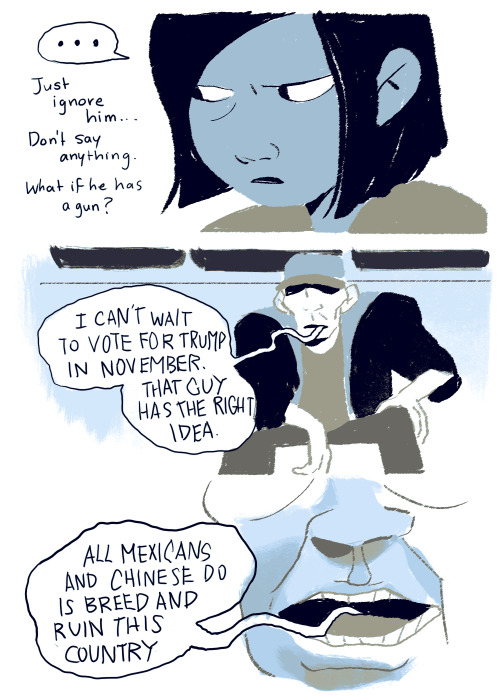

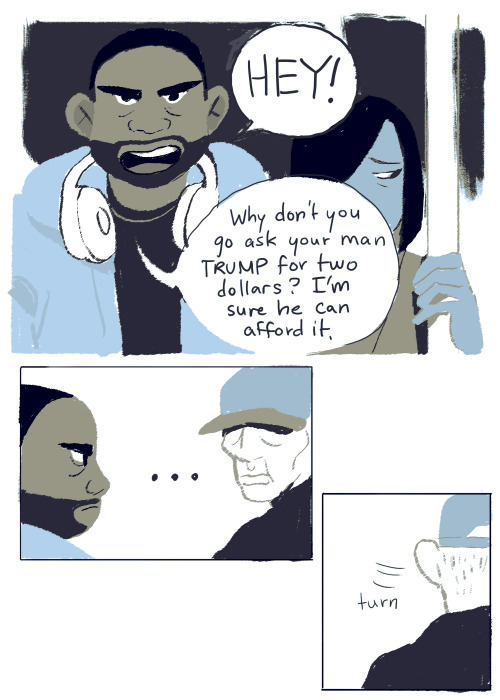

It’s been an emotional week. I wanted to share this encounter I had with a very hateful man on the Pittsburgh bus because it reminds me that there are brave people in this world. Let’s all do everything we can to stand up for each other.

The winners of the Miss Perfect Posture contest at a chiropractors convention, USA, 1956

via reddit

» Medical Specialties «

On this day in 1996, then-World Chess Champion Garry Kasparov makes his first move in the sixth game against Deep Blue, IBM’s supercomputer. Kasparov emerged the victor, winning three games, drawing in two, and losing one.

via reddit

“I came to America when I was six years old. Mom said she brought us here so that we’d have opportunities in life. She said that back in the Bahamas, it’s only the ‘haves’ and the ‘have nots.’ She wanted us to have more choices. But I don’t think she fully understood how things work here. She was a news reporter back in the Bahamas. But the only job she could get here was taking care of oldpeople. My dad could only work construction. We moved to four different states just so they could find work. They always told me, ‘Just study hard in school and everything will work out fine.’ So that was my plan. I got all A’s up until the 11th grade– except for one B in math. My goal was to get top twenty in my class, then go to college, then get a degree, and then get a job. I realized the truth my senior year. My guidance counselor told me I couldn’t get a loan. I couldn’t get financial aid. Even if I could find a way to pay for school, I probably couldn’t get a job. I felt so mad at everyone. There were some kids who completely slacked off in school, but even they were going to college. I started having panic attacks. My dad told me not to worry. He called me a ‘doubting Peter.’ He invited all his friends over to a fish fry to help raise money. And he did get $3,000. But that wasn’t enough. So I searched really hard on the Internet and found the Dream.us scholarship. My mom was so excited when I got it. They’re paying for me to go to Queens College. Now my mom’s really scared again because DACA got revoked. She’s crying all the time at work. I try to tell her that no matter what happens, we’re not going to die. We just might have to start over.”

-

greensuncolor reblogged this · 5 years ago

greensuncolor reblogged this · 5 years ago -

katyastrophe reblogged this · 7 years ago

katyastrophe reblogged this · 7 years ago -

katyastrophe liked this · 7 years ago

katyastrophe liked this · 7 years ago -

forthefuture-fish-blog reblogged this · 7 years ago

forthefuture-fish-blog reblogged this · 7 years ago -

crazychild2 liked this · 8 years ago

crazychild2 liked this · 8 years ago -

yagodichjagodic reblogged this · 8 years ago

yagodichjagodic reblogged this · 8 years ago -

rabaukentochter reblogged this · 8 years ago

rabaukentochter reblogged this · 8 years ago -

colordrifter reblogged this · 8 years ago

colordrifter reblogged this · 8 years ago -

mordinette liked this · 8 years ago

mordinette liked this · 8 years ago -

biggestdisappointmentinwarfare reblogged this · 8 years ago

biggestdisappointmentinwarfare reblogged this · 8 years ago -

dykehat liked this · 8 years ago

dykehat liked this · 8 years ago -

bewarewoof reblogged this · 8 years ago

bewarewoof reblogged this · 8 years ago -

cactuarkitty liked this · 8 years ago

cactuarkitty liked this · 8 years ago -

anotherfacelesswoman liked this · 8 years ago

anotherfacelesswoman liked this · 8 years ago -

mobulidae reblogged this · 8 years ago

mobulidae reblogged this · 8 years ago -

mistsonfire reblogged this · 8 years ago

mistsonfire reblogged this · 8 years ago -

ratchsellsfornax liked this · 8 years ago

ratchsellsfornax liked this · 8 years ago -

beqm liked this · 8 years ago

beqm liked this · 8 years ago -

barrysmullet reblogged this · 8 years ago

barrysmullet reblogged this · 8 years ago -

barrysmullet liked this · 8 years ago

barrysmullet liked this · 8 years ago -

biggestdisappointmentinwarfare liked this · 8 years ago

biggestdisappointmentinwarfare liked this · 8 years ago -

rock-paperback-scissors reblogged this · 8 years ago

rock-paperback-scissors reblogged this · 8 years ago -

originofcheese reblogged this · 8 years ago

originofcheese reblogged this · 8 years ago -

proudfanboy liked this · 8 years ago

proudfanboy liked this · 8 years ago -

rock-paperback-scissors liked this · 8 years ago

rock-paperback-scissors liked this · 8 years ago -

sarahmeeps reblogged this · 8 years ago

sarahmeeps reblogged this · 8 years ago -

silviaelric liked this · 8 years ago

silviaelric liked this · 8 years ago -

happyerathome liked this · 8 years ago

happyerathome liked this · 8 years ago -

waywardgypsea reblogged this · 8 years ago

waywardgypsea reblogged this · 8 years ago -

waywardgypsea liked this · 8 years ago

waywardgypsea liked this · 8 years ago -

thayerkerbasy liked this · 8 years ago

thayerkerbasy liked this · 8 years ago -

awed-frog reblogged this · 8 years ago

awed-frog reblogged this · 8 years ago -

acurseddragon reblogged this · 8 years ago

acurseddragon reblogged this · 8 years ago -

ashvanora liked this · 8 years ago

ashvanora liked this · 8 years ago -

the-sixth-dimension reblogged this · 8 years ago

the-sixth-dimension reblogged this · 8 years ago -

frostytherobot liked this · 8 years ago

frostytherobot liked this · 8 years ago -

citrusapples reblogged this · 8 years ago

citrusapples reblogged this · 8 years ago -

odderfodder liked this · 8 years ago

odderfodder liked this · 8 years ago -

suncolt liked this · 8 years ago

suncolt liked this · 8 years ago -

unikirin reblogged this · 8 years ago

unikirin reblogged this · 8 years ago