A Basic Schematic Of Why The Korean Alphabet Is So Cool, From Wright House:

A basic schematic of why the Korean alphabet is so cool, from Wright House:

Unlike almost every other alphabet in the world, the Korean alphabet did not evolve. It was invented in 1443 (promulgated in 1446) by a team of linguists and intellectuals commissioned by King Sejong the Great.

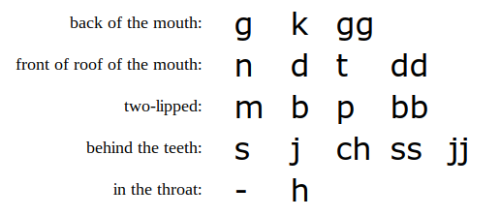

In the diagram [above], the Korean consonants are arranged into five main linguistic groups (one per row), depending on where in the mouth contact is made. Notice that there is a graphic element common to all the consonants in a particular row. The first consonant in each row is the most basic and is graphically the simplest; this representative consonant for each group is the building block for the other characters in that group. Certain of these modifications are systematic, and yield similarly modified characters in several groups, such as adding a horizontal line to a simple consonant (a “stop” consonant–such as t/d or p/b–rather than a nasal consonant) to form the aspirated consonants (those made with extra air) and doubling simple consonants to form “tense” consonants (no real equivalent in English).

Notice that the five representative consonants (the ones in the first column in the upper part of the diagram) are also depicted in the drawings that make up the lower part of the diagram showing the relevant part of the mouth involved. Ingeniously, each of these representative consonants is a kind of simplified schematic diagram showing the position of the mouth in forming those consonants.

More details, including subsequent historical changes to Hangul, in the Wikipedia article.

More Posts from Philosophical-amoeba and Others

On this day, 29th April 1770, Captain James Cook first landed at Botany Bay, (Sydney, Australia).

James Cook, with Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander landed at Kurnell in the afternoon of April 29th 1770, in search of fresh water. In the next few days, excursions around the bay were undertaken and samples of native flora collected, which proved so plentiful that Cook named the area Botany Bay.

The State Library of New South Wales holds many items relating to this voyage of the Endeavour, including Joseph Banks Journal and a copy of James Cook’s Endeavour log.

Portrait of Captain James Cook / painted by Sir Nathaniel Dance. Engraved by Cosmo Armstrong. State Library of New South Wales.

A Journal of the proceedings of His Majesty’s Bark Endeavour on a voyage round the world, by Lieutenant James Cook, Commander, commencing the 25th of May 1768 - 23 Oct. 1770 - Entrance of Endeavour River and Botany Bay Maps

Samurai armour.

A chart I made showing the names of the various main components of a suit of “modern samurai armour” or tosei gusoku. Tosei gusoku refers to armour worn by samurai that began to appear during the middle of the Muromachi Period (1337-1573) with the introduction of firearms.

A full suit of tosei gusoku as shown in my chart would have weighed in at around 30 kilograms or so including weapons - there is after all a considerable amount of iron plates and lacing!

Lower class samurai such as foot soldiers (ashigaru) would have carried their own rations, bedding, and other equipment, but their armour was somewhat lighter being generally less ornamented.

At this point in time, known in Japanese history as the Sengoku Period or the Warring States Period, the most common samurai weapon was the spear followed by the bow and arrow. The sword at this point in time was a secondary weapon relied upon during close combat.

The sword carried during this period was the longer, gracefully curved tachi and was worn edge down on the left side supported either by it’s own tachi mounting (tachi koshirae) or by using a special leather “sling” (koshiate) if it was mounted without hangers (ashi).

Another shorter sword called a chisagatana - literally “little sword” - was carried together with the tachi at the left hip up until the Momoyama period (1573-1603) when it was abandoned. The chisagatana was originally a throw away weapon reserved for use by conscript foot soldiers (ashigaru), but higher ranking samurai soon took up the carrying of one as a back up weapon.

Higher ranked samurai, those in charge of troops and generals in particular, also carried a short stout blade called a metezashi at the right hip, with the handle facing forwards. This weapon was designed for extreme close combat and used to penetrate the weak spots in an opponents armour. When swords were crossed, the metezashi could be drawn with the left hand and thrust into the opponent’s armpits. It could also be drawn with the right hand and thrown underarm in an instant to distract and stun an opponent before following up with the sword.

© James Kemlo

#Feathursday: Innate and Learned Behaviors

Once again we bring you a portion of the educational series Man: A Course of Study. This booklet uses the Herring Gull to teach innate and learned behaviors. We wish we knew who the illustrator of this booklet was because they’ve done a great job helping us understand how baby bird brains work.

Man: A Course of Study was developed by Jerome S. Bruner, an American psychologist who wanted to build a curriculum to teach fifth graders about what it is to be human. He often used animals as contrast to help explain the biological nature of humans.

From the teaching series, Man: A Course of Study published by Curriculum Development Associates. Our copy is the first commercial edition published in 1970.

More Feathursday posts

Some of our other posts from Man: A Course of Study

Julie D’Aubigny was a 17th-century bisexual French opera singer and fencing master who killed or wounded at least ten men in life-or-death duels, performed nightly shows on the biggest and most highly-respected opera stage in the world, and once took the Holy Orders just so that she could sneak into a convent and shag a nun.

(via Feminism)

These travel booklets from throughout the UK were collected by Barbara Denison over the course of three decades, part of a larger collection consisting of dozens of volumes. Text-dense and diagram-heavy guides like these were meant to both give guidance while visiting and act as inexpensive momentos afterwards. Most of the booklets in the collection concern cathedrals, abbeys, and ruined castles that Denison visited over the course of her travels.

Marine biology basics: a reading list

Someone recently asked me to “explain to me the basics of marine biology“ and I didn’t even know where to begin because that’s a HUGE topic with so much interesting stuff to think about. I asked some of my fellow scientists on twitter and we put together a list of good reading and watching to get an overview of what marine biology is all about. This list is broken down by ages. Comment with any more suggestions and I’ll add them!

Kids:

1)National Geographic Kids, Really Wild Animals, Deep Sea Dive (recommended by @DrKatfish on twitter) I watched this video when I was a kid and have been hooked on cephalopods ever since. If you listened to me on NPR’s Science Friday, this was the video I was talking about!

2) The Magic Schoolbus- on the ocean floor (recommended by @easargent184 and @mirandaRHK on twitter)

Amazon link: https://www.amazon.com/Magic-School-Bus-Ocean-Floor/dp/0590414313#reader_0590414313

3) Ocean Sunlight- How tiny plants feed the seas (recommended by @ColemanLab on twitter)

Amazon link:https://www.amazon.com/Ocean-Sunlight-Tiny-Plants-Feed/dp/0545273226

All ages

There are a TON of resources on The Bridge, so that’s a good place to start.

1) Blue Planet Series (recommended by @PaulSFenton on twitter) Great series, it’s on netflix and amazon

2) A Day in the life of a marine biologist (recommended by @Napaaqtuk on twitter)

3) Diving Deep with Sylvia Earle (recommended by @Napaaqtuk on twitter)

4) My wish: Protext our Oceans (Sylvia Earle) (also recommended by @Napaaqtuk on twitter)

Adults

1) At the Water’s Edge (Recommended by @PaulSFenton on twitter) “More a book about evolution featuring marine animals but still a v. good read.“

2) Four Fish: The future of the last wild Food (Recommended by me!) A great book about fisheries

3) Kraken : The Curious, Exciting, and Slightly Disturbing Science of Squid (Recommended by me)

4) The Edge of the Sea by Rachel Carson (recommended by @MirandaRHK on twitter)

5) The Sea Around Us- Rachel Carson (Recommended by @aecahill on twitter)

6) An Unnatural History of the Sea- Callum Roberts

How Tattooing Really Works

1. Tattooing causes a wound that alerts the body to begin the inflammatory process, calling immune system cells to the wound site to begin repairing the skin. Specialized cells called macrophages eat the invading material (ink) in an attempt to clean up the inflammatory mess.

2. As these cells travel through the lymphatic system, some of them are carried back with a belly full of dye into the lymph nodes while others remain in the dermis. With no way to dispose of the pigment, the dyes inside them remain visible through the skin.

3. Some of the ink particles are also suspended in the gel-like matrix of the dermis, while others are engulfed by dermal cells called fibroblasts. Initially, ink is deposited into the epidermis as well, but as the skin heals, the damaged epidermal cells are shed and replaced by new, dye-free cells with the topmost layer peeling off like a healing sunburn.

4. Dermal cells, however, remain in place until they die. When they do, they are taken up, ink and all, by younger cells nearby so the ink stays where it is.

5. So a single tattoo may not truly last forever, but tattoos have been around longer than any existing culture. And their continuing popularity means that the art of tattooing is here to stay.

From the TED-Ed Lesson What makes tattoos permanent? - Claudia Aguirre

Animation by TOGETHER

New CDC Research Debunks Agency’s Assertion That Mercury in Vaccines Is Safe

The CDC study, Alkyl Mercury-Induced Toxicity: Multiple Mechanisms of Action, appeared last month in the journal, Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. The 45-page meta-review of relevant science examines the various ways that mercury harms the human body. Its authors, John F. Risher, PhD, and Pamela Tucker, MD, are researchers in the CDC’s Division of Toxicology and Human Health Sciences, Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.

“This scientific paper is the one of most important pieces of research to come out of the CDC in a decade,” Paul Thomas, M.D., a Dartmouth-trained pediatrician who has been practicing medicine for 30 years, said. “It confirms what so many already suspected: that public health officials have been making a terrible mistake in recommending that we expose babies and pregnant women to this neurotoxin. I regret to say that I gave these shots to children. The CDC led us all to believe that it was perfectly safe.”

Among the findings of the CDC’s new study:

Methylmercury, the highly-regulated neurotoxin found in fish, and ethylmercury (found in medical products, including influenza and tetanus vaccines, ear drops and nasal sprays) are similarly toxic to humans. Methylmercury and ethylmercury share common chemical properties, and both significantly disrupt central nervous system development and function.

Thimerosal is extremely toxic at very low exposures and is more damaging than methylmercury in some studies. For example, ethylmercury is even more destructive to the mitochondria in cells than methylmercury.

The ethylmercury in thimerosal does not leave the body quickly as the CDC once claimed, but is metabolized into highly neurotoxic forms.

-

jayjayzzzzzz liked this · 6 months ago

jayjayzzzzzz liked this · 6 months ago -

harvnote liked this · 1 year ago

harvnote liked this · 1 year ago -

seraphaltima liked this · 1 year ago

seraphaltima liked this · 1 year ago -

elisetheasshole reblogged this · 1 year ago

elisetheasshole reblogged this · 1 year ago -

elisetheasshole liked this · 1 year ago

elisetheasshole liked this · 1 year ago -

happilykrispygalaxypensieri liked this · 2 years ago

happilykrispygalaxypensieri liked this · 2 years ago -

keendaanmaa liked this · 4 years ago

keendaanmaa liked this · 4 years ago -

keendaanmaa reblogged this · 4 years ago

keendaanmaa reblogged this · 4 years ago -

weissguertena liked this · 4 years ago

weissguertena liked this · 4 years ago -

ninomeira liked this · 4 years ago

ninomeira liked this · 4 years ago -

d20owlbear liked this · 4 years ago

d20owlbear liked this · 4 years ago -

studyingfluff reblogged this · 4 years ago

studyingfluff reblogged this · 4 years ago -

zlearning-korean-with-myself reblogged this · 5 years ago

zlearning-korean-with-myself reblogged this · 5 years ago -

sexemese123 liked this · 5 years ago

sexemese123 liked this · 5 years ago -

a-shade-in-between liked this · 5 years ago

a-shade-in-between liked this · 5 years ago -

sigilator liked this · 5 years ago

sigilator liked this · 5 years ago -

theegoist liked this · 5 years ago

theegoist liked this · 5 years ago -

redajin liked this · 5 years ago

redajin liked this · 5 years ago -

sunshynegrll liked this · 5 years ago

sunshynegrll liked this · 5 years ago -

ricardelo liked this · 5 years ago

ricardelo liked this · 5 years ago -

cottonwoolfairy liked this · 5 years ago

cottonwoolfairy liked this · 5 years ago -

glyptolite reblogged this · 5 years ago

glyptolite reblogged this · 5 years ago -

burntorbit liked this · 6 years ago

burntorbit liked this · 6 years ago -

tinkerbell0007 liked this · 6 years ago

tinkerbell0007 liked this · 6 years ago -

gishifu reblogged this · 6 years ago

gishifu reblogged this · 6 years ago -

thetrashknightofbreath reblogged this · 6 years ago

thetrashknightofbreath reblogged this · 6 years ago -

chironsgate reblogged this · 6 years ago

chironsgate reblogged this · 6 years ago -

waffletardis liked this · 6 years ago

waffletardis liked this · 6 years ago -

genderqueerpond liked this · 6 years ago

genderqueerpond liked this · 6 years ago -

willowcat33 liked this · 6 years ago

willowcat33 liked this · 6 years ago -

animate-mush reblogged this · 6 years ago

animate-mush reblogged this · 6 years ago -

geeneelee reblogged this · 6 years ago

geeneelee reblogged this · 6 years ago -

geeneelee liked this · 6 years ago

geeneelee liked this · 6 years ago -

uchihasasukeofficial reblogged this · 6 years ago

uchihasasukeofficial reblogged this · 6 years ago -

the-foxy-dreamer liked this · 6 years ago

the-foxy-dreamer liked this · 6 years ago -

roark8k0621 liked this · 6 years ago

roark8k0621 liked this · 6 years ago -

springirls-on-time reblogged this · 6 years ago

springirls-on-time reblogged this · 6 years ago -

springirls-on-time liked this · 6 years ago

springirls-on-time liked this · 6 years ago -

izmarvelous liked this · 6 years ago

izmarvelous liked this · 6 years ago

A reblog of nerdy and quirky stuff that pique my interest.

291 posts