Marine Biology Basics: A Reading List

Marine biology basics: a reading list

Someone recently asked me to “explain to me the basics of marine biology“ and I didn’t even know where to begin because that’s a HUGE topic with so much interesting stuff to think about. I asked some of my fellow scientists on twitter and we put together a list of good reading and watching to get an overview of what marine biology is all about. This list is broken down by ages. Comment with any more suggestions and I’ll add them!

Kids:

1)National Geographic Kids, Really Wild Animals, Deep Sea Dive (recommended by @DrKatfish on twitter) I watched this video when I was a kid and have been hooked on cephalopods ever since. If you listened to me on NPR’s Science Friday, this was the video I was talking about!

2) The Magic Schoolbus- on the ocean floor (recommended by @easargent184 and @mirandaRHK on twitter)

Amazon link: https://www.amazon.com/Magic-School-Bus-Ocean-Floor/dp/0590414313#reader_0590414313

3) Ocean Sunlight- How tiny plants feed the seas (recommended by @ColemanLab on twitter)

Amazon link:https://www.amazon.com/Ocean-Sunlight-Tiny-Plants-Feed/dp/0545273226

All ages

There are a TON of resources on The Bridge, so that’s a good place to start.

1) Blue Planet Series (recommended by @PaulSFenton on twitter) Great series, it’s on netflix and amazon

2) A Day in the life of a marine biologist (recommended by @Napaaqtuk on twitter)

3) Diving Deep with Sylvia Earle (recommended by @Napaaqtuk on twitter)

4) My wish: Protext our Oceans (Sylvia Earle) (also recommended by @Napaaqtuk on twitter)

Adults

1) At the Water’s Edge (Recommended by @PaulSFenton on twitter) “More a book about evolution featuring marine animals but still a v. good read.“

2) Four Fish: The future of the last wild Food (Recommended by me!) A great book about fisheries

3) Kraken : The Curious, Exciting, and Slightly Disturbing Science of Squid (Recommended by me)

4) The Edge of the Sea by Rachel Carson (recommended by @MirandaRHK on twitter)

5) The Sea Around Us- Rachel Carson (Recommended by @aecahill on twitter)

6) An Unnatural History of the Sea- Callum Roberts

More Posts from Philosophical-amoeba and Others

Beautiful Blaschka glass model of a Glaucus sea slug.

These amazing animals can give a painful sting if handled. This is because they feed on colonial cnidarians such as Portuguese man o’ war and store the venomous nematocysts of their prey for self-protection.

Mae’s Millinery Shop

Photo: Photograph of Mae Reeves and a group of women standing on stairs, Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Gift from Mae Reeves and her children, Donna Limerick and William Mincey, Jr.

African American women have been wearing fancy hats for generations to church. In 1940, Mae Reeves started Mae’s Millinery Shop in 1940 in Philadelphia, PA with a $500 bank loan. The shop stayed open until 1997 and helped dress some of the most famous African American women in the country, including iconic singers Marian Anderson, Ella Fitzgerald and Lena Horne.

Reeves was known for making all of her customers feel welcomed and special, whether they were domestic workers, professional women, or socialites from Philadelphia’s affluent suburban Main Line. Customer’s at Mae’s would sit at her dressing table or on her settee, telling stories and sharing their troubles.

Photo: Pink mushroom hat with flowers from Mae’s Millinery Shop, Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. In our Power of Place exhibition, we recreated a portion of Reeves’ shop to showcase this African American tradition. Our shop includes its original red-neon sign, sewing machine, antique store furniture and hats. View artifacts from Mae’s Millinery Shop in our collection: s.si.edu/2oVlbFj

The late effects of stress: New insights into how the brain responds to trauma

Mrs. M would never forget that day. She was walking along a busy road next to the vegetable market when two goons zipped past on a bike. One man’s hand shot out and grabbed the chain around her neck. The next instant, she had stumbled to her knees, and was dragged along in the wake of the bike. Thankfully, the chain snapped, and she got away with a mildly bruised neck. Though dazed by the incident, Mrs. M was fine until a week after the incident.

Then, the nightmares began.

She would struggle and yell and fight in her sleep every night with phantom chain snatchers. Every bout left her charged with anger and often left her depressed. The episodes continued for several months until they finally stopped. How could a single stressful event have such extended consequences?

A new study by Indian scientists has gained insights into how a single instance of severe stress can lead to delayed and long-term psychological trauma. The work pinpoints key molecular and physiological processes that could be driving changes in brain architecture.

The team, led by Sumantra Chattarji from the National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS) and the Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine (inStem), Bangalore, have shown that a single stressful incident can lead to increased electrical activity in a brain region known as the amygdala. This activity sets in late, occurring ten days after a single stressful episode, and is dependent on a molecule known as the N-Methyl-D-Aspartate Receptor (NMDA-R), an ion channel protein on nerve cells known to be crucial for memory functions.

The amygdala is a small, almond-shaped groups of nerve cells that is located deep within the temporal lobe of the brain. This region of the brain is known to play key roles in emotional reactions, memory and making decisions. Changes in the amygdala are linked to the development of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), a mental condition that develops in a delayed fashion after a harrowing experience.

Previously, Chattarji’s group had shown that a single instance of acute stress had no immediate effects on the amygdala of rats. But ten days later, these animals began to show increased anxiety, and delayed changes in the architecture of their brains, especially the amygdala.

“We showed that our study system is applicable to PTSD. This delayed effect after a single episode of stress was reminiscent of what happens in PTSD patients,” says Chattarji. “We know that the amygdala is hyperactive in PTSD patients. But no one knows as of now, what is going on in there,” he adds.

Investigations revealed major changes in the microscopic structure of the nerve cells in the amygdala. Stress seems to have caused the formation of new nerve connections called synapses in this region of the brain. However, until now, the physiological effects of these new connections were unknown.

In their recent study, Chattarji’s team has established that the new nerve connections in the amygdala lead to heightened electrical activity in this region of the brain.

“Most studies on stress are done on a chronic stress paradigm with repeated stress, or with a single stress episode where changes are looked at immediately afterwards – like a day after the stress,” says Farhana Yasmin, one of the Chattarji’s students. “So, our work is unique in that we show a reaction to a single instance of stress, but at a delayed time point,” she adds.

Furthermore, a well-known protein involved in memory and learning, called NMDA-R has been recognised as one of the agents that bring about these changes. Blocking the NMDA-R during the stressful period not only stopped the formation of new synapses, it also blocked the increase in electrical activity at these synapses.

“So we have for the first time, a molecular mechanism that shows what is required for the culmination of events ten days after a single stress,” says Chattarji. “In this study, we have blocked the NMDA Receptor during stress. But we would like to know if blocking the molecule after stress can also block the delayed effects of the stress. And if so, how long after the stress can we block the receptor to define a window for therapy,” he adds.

Chattarji’s group first began their investigations into how stress affects the amygdala and other regions of the brain around ten years ago. The work has required the team to employ an array of highly specialised and diverse procedures that range from observing behaviour to recording electrical signals from single brain cells and using an assortment of microscopy techniques. “To do this, we have needed to use a variety of techniques, for which we required collaborations with people who have expertise in such techniques,” says Chattarji. “And the glue for such collaborations especially in terms of training is vital. We are very grateful to the Wadhwani Foundation that supports our collaborative efforts and to the DBT and DAE for funding this work,” he adds.

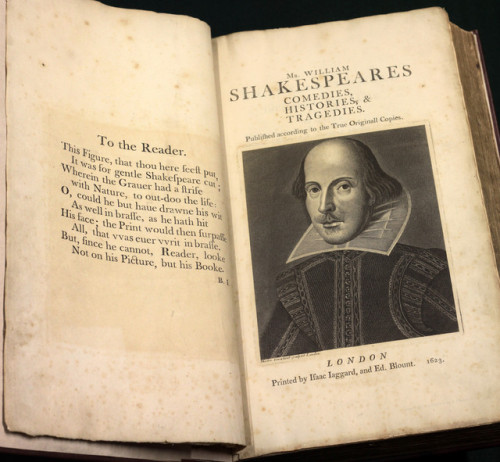

Comedies Histories Tragedies

Mr William Shakespeare

London Iaggard and Blount 1623

Textual reprint of the First Folio published by J Wright 1807

The Screwtape Letters C S Lewis London Geoffrey Bles - The Centenary Press 1942 - First Published February 1942, Reprinted March 1942, Reprinted March 1942

dedicated to J R R Tolkien

Harmonograph, H. Irwine Whitty, 1893

“The facts that musical notes are due to regular air-pulses, and that the pitch of the note depends on the frequency with which these pulses succeed each other, are too well known to require any extended notice. But although these phenomena and their laws have been known for a very long time, Chladni, late in the last century, was the first who discovered that there was a connection between sound and form.”

source here

Laplace transform table. Source. (I’m obsessed. <3 And figured y’all would like this one, too!)

Timbuktu was a center of the manuscript trade, with traders bringing Islamic texts from all over the Muslim world. Despite occupations and invasions of all kinds since then, scholars managed to preserve and even restore hundreds of thousands of manuscripts dating from the 13th century.

But that changed when militant Islamists backed by al-Qaida arrived in 2012.

The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu tells the story of librarian Abdel Kader Haidara, who organized and oversaw a secret plot to smuggle hundreds of thousands of medieval manuscripts out of Timbuktu before they could be destroyed by Islamist rebels.

Hear author Joshua Hammer tell the story here.

– Petra

Word of the Day: potlatch

n. An opulent ceremonial feast (among certain North American Indian peoples of the north-west coast) at which possessions are given away or destroyed to display wealth or enhance prestige

Image: “Klallam people at Port Townsend” by James Gilchrist Swan. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

-

is-this-the-real-life liked this · 5 years ago

is-this-the-real-life liked this · 5 years ago -

somefishdood liked this · 5 years ago

somefishdood liked this · 5 years ago -

turtlenecklight liked this · 6 years ago

turtlenecklight liked this · 6 years ago -

hhideout liked this · 6 years ago

hhideout liked this · 6 years ago -

jenniebassham liked this · 6 years ago

jenniebassham liked this · 6 years ago -

gotta-ketchum-all reblogged this · 6 years ago

gotta-ketchum-all reblogged this · 6 years ago -

tank-baby liked this · 6 years ago

tank-baby liked this · 6 years ago -

skelemonjack liked this · 6 years ago

skelemonjack liked this · 6 years ago -

pango-doots liked this · 7 years ago

pango-doots liked this · 7 years ago -

micabell liked this · 7 years ago

micabell liked this · 7 years ago -

a-deadass-bird liked this · 7 years ago

a-deadass-bird liked this · 7 years ago -

cosmicvulture liked this · 7 years ago

cosmicvulture liked this · 7 years ago -

munnyrabbit liked this · 7 years ago

munnyrabbit liked this · 7 years ago -

raizinghell liked this · 7 years ago

raizinghell liked this · 7 years ago -

incoherentscorpio liked this · 7 years ago

incoherentscorpio liked this · 7 years ago -

excuse-my-disdain liked this · 7 years ago

excuse-my-disdain liked this · 7 years ago -

leafywrites reblogged this · 7 years ago

leafywrites reblogged this · 7 years ago -

k-911 reblogged this · 7 years ago

k-911 reblogged this · 7 years ago -

asimplejude reblogged this · 7 years ago

asimplejude reblogged this · 7 years ago -

asimplejude liked this · 7 years ago

asimplejude liked this · 7 years ago -

lirio-dendron reblogged this · 7 years ago

lirio-dendron reblogged this · 7 years ago -

msva9 liked this · 7 years ago

msva9 liked this · 7 years ago -

musical-pigeon liked this · 7 years ago

musical-pigeon liked this · 7 years ago -

beware-nerd-alert reblogged this · 7 years ago

beware-nerd-alert reblogged this · 7 years ago -

livthesquido3o liked this · 7 years ago

livthesquido3o liked this · 7 years ago -

starrynightcinema reblogged this · 7 years ago

starrynightcinema reblogged this · 7 years ago -

zenyahtta liked this · 7 years ago

zenyahtta liked this · 7 years ago -

araneidae9 liked this · 7 years ago

araneidae9 liked this · 7 years ago -

artemisaro liked this · 7 years ago

artemisaro liked this · 7 years ago -

star-scales reblogged this · 7 years ago

star-scales reblogged this · 7 years ago -

scyphozoic reblogged this · 7 years ago

scyphozoic reblogged this · 7 years ago -

scyphozoic liked this · 7 years ago

scyphozoic liked this · 7 years ago -

kiloueka reblogged this · 7 years ago

kiloueka reblogged this · 7 years ago -

70-mph liked this · 7 years ago

70-mph liked this · 7 years ago -

johnpatootie liked this · 7 years ago

johnpatootie liked this · 7 years ago -

v0iddarling liked this · 7 years ago

v0iddarling liked this · 7 years ago -

tea-and-a-story reblogged this · 7 years ago

tea-and-a-story reblogged this · 7 years ago -

youkaisky liked this · 7 years ago

youkaisky liked this · 7 years ago -

semicossyphus-pulcher liked this · 7 years ago

semicossyphus-pulcher liked this · 7 years ago -

nonexpressiveusername reblogged this · 7 years ago

nonexpressiveusername reblogged this · 7 years ago

A reblog of nerdy and quirky stuff that pique my interest.

291 posts