Cosplay, To The 110 😶

Cosplay, to the 110 😶

I normally don't repost stuff but OMFG

if anyone finds the op on douyin I'm grateful 🙏

More Posts from Weishenmewwx and Others

Please can you explain the difference of meaning between hanfu and huafu ? Sorry if you already got the question

Hi, thanks for the question, and sorry for taking ages to reply! (hanfu photo via)

The term “hanfu” (traditional Chinese: 漢服, simplified Chinese: 汉服) literally means “Han clothing”, and refers to the traditional clothing of the Han Chinese people. “Han” (漢/汉) here refers to the Han Chinese ethnic group (not the Han dynasty), and “fu” (服) means “clothing”. As I explained in this post, the modern meaning of “hanfu” is defined by the hanfu revival movement and community. As such, there is a lot of gatekeeping by the community around what is or isn’t hanfu (based on historical circumstances, cultural influences, tailoring & construction, etc). This isn’t a bad thing - in fact, I think gatekeeping to a certain extent is helpful and necessary when it comes to reviving and defining historical/traditional clothing. However, this also led to the need for a similarly short, catchy term that would include all Chinese clothing that didn’t fit the modern definition of hanfu -- enter huafu.

The term “huafu” (traditional Chinese: 華服, simplified Chinese: 华服) as it is used today has a broader definition than hanfu. “Hua” (華/华) refers to the Chinese people (中华民族/zhonghua minzu), and again “fu” (服) means “clothing”. It is an umbrella term for all clothing that is related to Chinese history and/or culture. Thus all hanfu is huafu, but not all huafu is hanfu. Below are examples of Chinese clothing that are generally not considered hanfu by the hanfu community for various reasons, but are considered huafu:

1. Most fashions that originated during the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), especially late Qing, including the Qing aoqun & aoku for women, and the Qing changshan and magua for men. I wrote about whether Qing dynasty clothing can be considered hanfu here. Tangzhuang, which is an updated form of the Qing magua popularized in 2001, can also fit into this category. Below - garments in the style of Han women’s clothing during the Qing dynasty (清汉女装) from 秦綿衣莊 (1, 2).

2. Fashions that originated during the Republican era/minguo (1912-1949), including the minguo aoqun & aoku and qipao/cheongsam for women, and the minguo changshan for men (the male equivalent of the women’s qipao). I wrote about why qipao isn’t considered hanfu here. Below - minguo aoqun (left) & qipao (right) from 嬉姷.

Below - Xiangsheng (crosstalk) performers Zhang Yunlei (left) & Guo Qilin (right) in minguo-style men’s changshan (x). Changshan is also known as changpao and dagua.

3. Qungua/裙褂 and xiuhefu/秀禾服, two types of Chinese wedding garments for brides that are commonly worn today. Qungua originated in the 18th century during the Qing dynasty, and xiuhefu is a modern recreation of Qing wedding dress popularized in 2001 (x). Below - left: qungua (x), right: xiuhefu (x).

4. Modified hanfu (改良汉服/gailiang hanfu) and hanyuansu/汉元素 (hanfu-inspired fashion), which do not fit in the orthodox view of hanfu. Hanfu mixed with sartorial elements of other cultures also fit into this category (e.g. hanfu lolita). From the very start of the hanfu movement, there’s been debate between hanfu “traditionalists” and “reformists”, with most members being somewhere in the middle, and this discussion continues today. Below - hanyuansu outfits from 川黛 (left) and 远山乔 (right).

5. Performance costumes, such as Chinese opera costumes (戏服/xifu) and Chinese dance costumes. These costumes may or may not be considered hanfu depending on the specific style. Dance costumes, in particular, may have non-traditional alterations to make the garment easier to dance in. Dunhuang-style feitian (apsara) costumes, which I wrote about here, can also fit into this category. Below - left: Chinese opera costume (x), right: Chinese dance costume (x).

6. Period drama costumes and fantasy costumes in popular media (live-action & animation, games, etc.), commonly referred to as guzhuang/古装 (lit. “ancient costumes”). Chinese period drama costumes are of course based on hanfu, and may be considered hanfu if they are historically accurate enough. However, as I wrote about here, a lot of the time there are stylistic inaccuracies (some accidental, some intentional) that have become popularized and standardized over time (though this does seem to be improving in recent years). This is especially prevalent in the wuxia and xianxia genres. Similarly, animated shows & games often have characters dressed in “fantasy hanfu” that are essentially hanfu with stylistic modifications. Below - left: Princess Taiping in historical cdrama 大明宫词/Palace of Desire (x), right: Wei Wuxian and Lan Wangji in wuxia/xianxia cdrama 陈情令/The Untamed (x).

7. Any clothing in general that purposefully utilizes Chinese style elements (embroidery, fabrics, patterns, motifs, etc). Chinese fashion brand Heaven Gaia is a well-known example of this. Below - Chinese-inspired designs by Heaven Gaia (x).

8. Technically, the clothing of China’s ethnic minorities also fit under the broad definition of huafu, but it’s rarely ever used in this way.

From personal observation, the term “huafu” is mainly used in the following situations:

1. Some large-scale events to promote Chinese clothing, such as the annual “华服日/Huafu Day”, will use “huafu” in their name for inclusivity.

2. For the same reason as above, Chinese clothing including hanfu will often be referred to as “huafu” on network television programs (ex: variety shows).

3. A few Chinese clothing shops on Taobao use “huafu” in their shop name. Two examples:

明镜华服/Mingjing Huafu - sells hanfu & hanyuansu.

花神妙华服/Huashenmiao Huafu - sells Qing dynasty-style clothing.

With the exception of the above, “huafu” is still very rarely used, especially compared to “hanfu”. It has such a broad definition that it’s just not needed in situations for which a more precise term already exists. However, I do think it’s useful as a short catch-all term for Chinese clothing that isn’t limited to the currently accepted definition of hanfu.

If anyone wants to add on or correct something, please feel free to do so! ^^

Hope this helps!

So during my second time watching Jiang Cheng walk across what I now know is a random mountain to meet Wen Qing, all I could think about was Wei Wuxian, Wen Qing, and Wen Ning’s plan and the fact that they must have been following him, like:

Wen Qing: should he really be walking across that field?

Wei Wuxian: I don’t know, I thought he would follow the path

Wen Ning: should we stop it now so he doesn’t trip and fall?

Wei Wuxian: naw let’s wait a bit, he needs to think it’s difficult

Wen Ning: is this a good place? can I ring the gong now?

Wei Wuxian: I think it’s good. wen qing?

Wen Qing: yeah yeah it’s fine. ring the stupid gong - I’ll lead him to a better spot

Wen Qing: I’m not going to wear the hat

Wei Wuxian: c’mon, you need to wear the hat

Wen Ning: yeah, wear the hat, a-jie

Wen Qing: he’s wearing a blindfold! he won’t be able to see my face anyway

Wei Wuxian: but what if he takes off the blindfold? what then, hmm? the hat is key

Wen Ning: yeah a-jie, the hat is key

Wen Qing: uuuuugh fine I’ll wear the hat

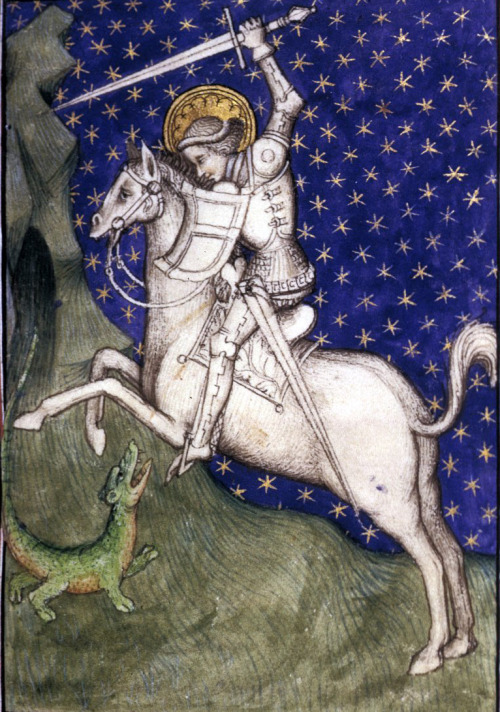

Ever see a depiction of St. George and the Dragon? It's pretty fair to say if you've seen one, you've seen them all: Georgie on a horse stabbing a flailing dragon creature, princess piously kneeling in the background, vague landscape alluding to the homeland of the artist's patron.

The most varied part is the dragons. No one had a real definition for the thing, it seemed. For your pleasure and entertainment, I have ranked some medieval depictions based on how impressive George's feat seems once you see the dragon.

Paolo Uccello, 1456

This is a terrifying beast. The hell is that. Uccello was one of the first experimenters with perspective, so the thing also looks surreal, like it's taking place on Mars, or a Windows 95 screensaver. I would not want to fight that, I would not want to be tied to that. (Sometimes the princess is tied to the dragon for some reason.) 10/10

Horse thoughts: Maybe if I look at the ground it will be gone when I look up

Unknown artist, c. 1505

This is a rare change of form for the dragon; it's the only one I've seen actually flying (or at least falling with style). It doesn't look particularly deterred by the spear through its throat, either. Also, George looks appropriately nervous. On the other hand, it hasn't got teeth, it seems to be fuzzy rather than having scaly armor, and George is bolstered by his army of Henry VII and his children, most of whom definitely didn't actually die in infancy. Still, wouldn't want to fight it, wouldn't want my pet sheep near it. (Sometimes the princess has a pet sheep for some reason.) 9/10

Horse thoughts: I am so glad I wore my mightiest feather helmet for this

Raphael, 1505

We are coming to Dragons With Problems. This guy looks about comparable in size to George, and does have wings, but doesn't seem to be using these things to his advantage (and has he only got one wing?) And how does he deal with the neck? He does have a comically small head, but holding it up with such a twisty neck seems complicated at best. But most egregiously, he is doing the shitty superheroine pose where he is somehow simultaneously showcasing his chest and his butt, with its unnecessarily defined butthole (more on this later) (regrettably). 8/10 bc it's Raphael

Horse thoughts: AM I THE BESTEST BOI? AM I DOING SUCH A GOOD JOB? WE R DRAGON SLAYING BUDDIEZ

The Beauchamp Hours, c. 1401

We had a spirited debate about this one at work. Again, the dragon has gotten smaller, and this one hasn't got even one wing. He's basically a crocodile. So the debate became: would you want to fight a crocodile if you had a horse and a pointy stick? Would the horse trample the animal, who can't get on its hind legs, or freak out and throw its rider? Would the pointy stick be enough to pierce the croc's thick hide? In this case, George seems to be controlling his horse and putting his pointy stick in the dragon's weak spot, so we can be impressed by his skill and strategy. However, his hat is dumb. 7/10

Horse thoughts: Dehhhh

Book of Hours, c. 1480

Here we have the same kind of croco-dragon, but George's focus on his strategy has gone out the window. He's flailing around, not even looking at his target, he's about to lose his pointy stick, he hasn't got a hand on the reins, and his sword seems to only be poking the invisible dragon over his shoulder. All he's got going for him is that his hat is slightly less dumb. 6/10

Horse thoughts: Yay, new friend! Come play with me, new fr- what is happening

Final dragons put behind this Read More for your safety:

Rogier van der Weyden, c. 1432

I'm thinking this guy is at least semi-aquatic. Webbed feet, wings that seem more like fins, bipedal but top-heavy, jaws that seem more for scooping than biting. Maybe she's crawled up here from the nearby body of water to lay her eggs, and this is all a big misunderstanding. Moreover, George's dagged sleeves seem entirely impractical for the situation. 5/10

Horse thoughts: i got my hed stuk in a jar and now it is this way forever

Unknown artist, c. 15th century

I hate this. I hate everything about it. Why has it got human eyes and teeth. Why is its nose melting. Why has it got a dick on its face and balls under its chin. The fin/wings are back but they look even more useless. Also, George is shifty as hell, schlumped over in his saddle with his bowler hat thing over his eyes. The baby dragon at the bottom eating some hapless would-be rescuer is kind of metal. 4/10 at least the thing is gonna die

Horse thoughts: I Have Smoked So Much Crack

Book of Hours, c. 1450

Remember what I said about the buttholes? First, sorry. Second, yeah, we're back to that. I'll admit this one is less about the danger from the dragon itself than the very specific choices the artist has made. They didn't need to do that. It's a lizard. They don't even have. And it's like they had an orifice budget and they skipped an exit wound for the spear to focus. Elsewhere. It's so detailed. And George had an even dumber hat. 2/10 take it away

Horse thoughts: I Have Smoked So Much Weed

Book of Hours, c. 1415

This is just bullying. There isn't even a princess. That is clearly an infant. Look at that smug look on George's face as he swings his sword that's bigger than the whole little guy. This is the equivalent of when DJT Jr. hunted those sleeping endangered sheep. 1/10

Horse thoughts: ....yikes

And this is the previous one, but now the baby dragon is cute. He's chubby. He's got toe beans. He's Puff the Magic Dragon. His eyes have already gone white, implying that George is just kicking its corpse around for funsies. What's the difference between the dragon and the lamb in the background? That the dragon is dead, like our innocence. This George is truly deserving of the dumbest hat of all. 0/10 plus one more butthole for the road

Horse thoughts: Perhaps it is we who are the buttholes.

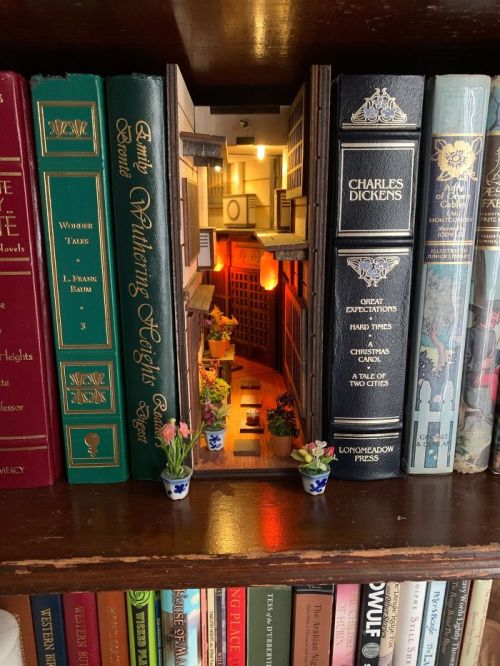

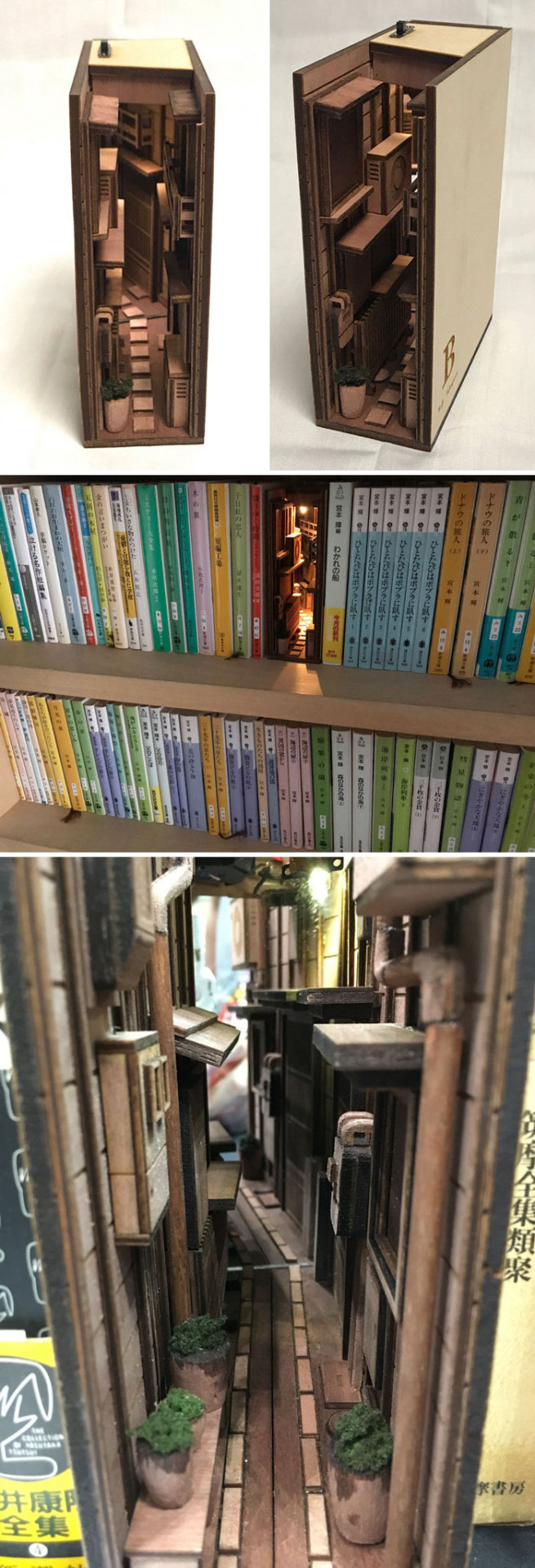

Bookshelf inserts

hey say that you can’t judge a book by its cover. But what if the cover alone can tell you the whole story? Welcome to the world of book nooks where creativity runs wild!

These hand-made creations will draw you into tiny places of wonder: from the hobbit hole to the Blade Runner-inspired apocalyptic alley or Lord of the Rings-themed door replica equipped with motion sensors.

This book nook my mother got on Ebay

A Magical bookshop in your own bookshelf

I made a booknook for a christmas gift, my inspiration was Blade Runner. It’s 11" X 6"

Not only are book nook inserts a fun way to train your creativity muscle, they can also be a solution to making reading great again. A recent study done by Pew Research Center showed that a staggering quarter of American adults don’t read books in any shape or form. The same study suggested that the likelihood of reading was directly linked to wealth and educational level. Add high levels of modern insomnia and full-time employment that leaves many of us drained at the end of the day, and the idea of opening a book seems unappealing, to say the least.

Now imagine yourself walking past a bookshelf full of these mini worlds—the dioramas of an alley. They catch your attention and you cannot help but see what’s inside. The pioneer of the book nook concept is the Japanese artist Monde. Monde introduced his creations to the Design Festa in 2018 and received overwhelming feedback. 178K likes on twitter later, Monde has become an inspiration to the aspiring arts and crafts lovers who join on r/booknooks to share their spectacular ideas.

Hobbit Hole

Design, print and paint a small shelf to decorate shelves

worlds hidden in a bookcase

A double wide endor inspired wilderness piece

Old Italy book nook

Diagon Alley booknook

Witch is watching you

Warhammer-style booknook

Creature from the Black Lagoon bookshelf monster

A booknook inspired by Les Miserables

source https://www.boredpanda.com/book-nook-shelf-inserts

I love this so much, thank you!😊❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️

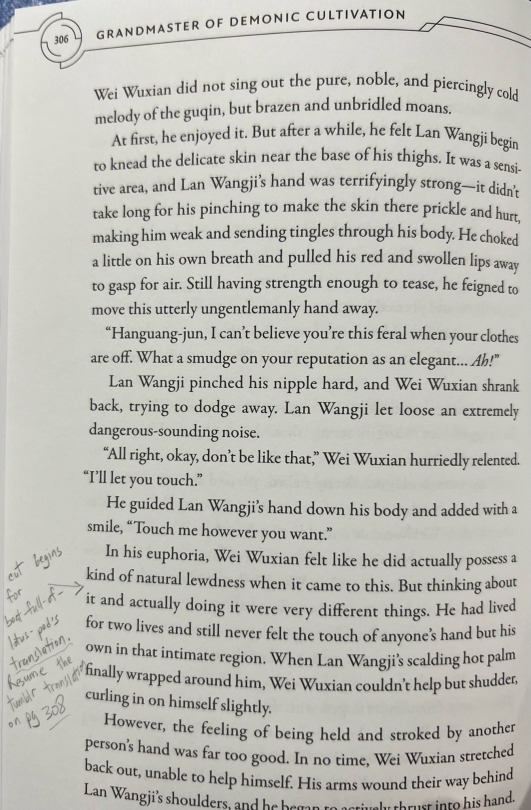

MDZS Volume 4 Annotations

Part 9, pages 293 - 309

Here begin The Edits.

My understanding, gleaned almost exclusively from reading tumblr, is that there are at least 3 versions of MDZS:

1) Original serialized story, published as it was written.

2) Cleaned-up story after the story was all done.

(I think this is the version that got published in Taiwan.)

3) Censored version, the only one that you can easily find online these days.

(This is the version that the ♥️Audio Drama♥️ is based on!)

While it’s awesome that Seven Seas didn’t censor MDZS, it’s also very sad that they didn’t incorporate all the sweet extra little scenes and adorable lines that MXTX added when she had to brutally cut out all the blatant physical intimacy (😢 that must have hurt 😢).

Here’s what to add back in, folks!

⭐️ 1)

WWX: “What do you want to do next?” He just barely restrained himself from saying “Whose house are you going to wreck next?”

LWJ furrowed his brow slightly and corrected WWX: “We.”

WWX: “Ok, ok. We.” (As in, “What will we do next, together.”)

LWJ nodded his head, and he even gave WWX the jujubes again. WWX wiped them on his clothes and took a few bites, thinking about how, in the middle of the night, Hanguang Jun wants Yiling Laozu to disturb the peace and make mischief with him.

If word of this got out, it would be disastrous.

Much more below the cut:

⭐️ 2)

After a moment, he tilted his head and asked, “How is it?”

WWX: “Hmm? What? How is it? … Good! Very good. I gladly bow down to your superiority!”

These were true statements. Even though he was drunk, Hanguang Jun’s handwriting was, as usual, exceedingly proper; WWX was ashamed at his own inferiority (re: handwriting) (handwriting is a big thing in Chinese culture).

LWJ nodded his head, and passed Bichen to WWX.

WWX: “…?…”

LWJ again tried to pass Bichen to him, and WWX accepted. He looked at the wall and noticed how there was a lot of space after the words “Lan Wangji,” then understood.

LWJ was waiting for him to write his own name up there!

LWJ stared at WWX unrelentingly, and WWX finally couldn’t take it anymore, saying “Ok, ok, ok. I’m writing. I’m writing.”

Resigned to this action (this fate), in the space after “Gusu LWJ,” he wrote “Yunmeng WWX.” Now, both of their names were side by side on the wall.

“Gusu LWJ, Yunmeng WWX, travelled here!”

⭐️ 3)

The sect rules of Gusu Lan were so strict, there was no way LWJ had ever had so much wild, crazy fun when he was little.

⭐️ 4) (an entire scene of Drunk LWJ exerting his dominance over a dog for the sake of WWX)

“Woof woof woof arf arf arf!”

Suddenly, an torrent of barking exploded like firecrackers in WWX’s ears. He screamed and instinctively jumped on top of LWJ: “Lan Zhan, save me!”

This household raised dogs?

In actuality, in the middle of this quiet night, WWX’s awful hollering and howling was much more terrifying than any dog’s barking. He was scared out of his wits, but LWJ’s expression did not change, and with one hand he held WWX and patted him soothingly, with the other hand he held his sword, then leapt lightly to the top of the wall; and from that position of superior height he looked down upon the wicked dog, and with a cold expression seemed to engage in a confrontation with it.

WWX had all 4 limbs wrapped around LWJ and his face buried in LWJ’s neck. His whole body was stiff, paralyzed. He screamed, “Don’t confront it! Go! Let’s go! Lan Zhan, get me away from here! Aughghghgh!!!”

While WWX was madly crying, the dog, upon seeing LWJ, had tucked its tail between its legs, extended its tongue, lowered its head, and was splayed on the ground crying; it didn’t dare bark anymore.

LWJ saw that he had achieved complete victory, then gently patted WWX twice more, held him tightly, then leapt down from the wall.

They had walked quite a ways away and didn’t hear a single bark; only then did WWX peel himself off of LWJ’s body. His eyes stared straight forward and his legs still trembled. LWJ patted his shoulder, expression focused on WWX as if asking if he was ok. WWX hadn’t fully calmed down yet, and with some effort took a deep breath, casually praising LWJ as he did so: “Hanguang Jun, you really are extraordinarily brave. Unparalleled!”

Hearing this, LWJ seemed to smile.

The moment was fleeting, and WWX thought that perhaps he was just seeing things. He was stunned.

A moment later, he sighed, rubbed his chin, and smiled. “Lan Zhan, now you know to regret not going to Lianhua Wu with me back then, right? Wait! Where are you going?! Don’t just run off!”

⭐️ 5)

WWX couldn’t help but tug on LWJ’s forehead ribbon. “You even order me around now?”

⭐️ 6)

WWX despaired. He gritted his teeth and pretended like everything was fine: “I’ll just help you pour over the bath water, ok? And the rest you can do yourself.” As he spoke, he made to dodge away from LWJ; suddenly, LWJ reached out and ripped off his sash.

⭐️ 7)

Seeing him this way, WWX’s heart inexplicably softened; he also felt it to be funny (Chinese doesn’t require subjects in sentences, so I’m not sure if WWX finds LWJ funny or the situation laughable or both). This person really has been this way since he was little — the things he wants, he would never say in words, but he would fiercely pursue with his actions. So, then, WWX dragged LWJ back to the tub, saying “Ok, I’ll help you bathe. Come here.” In his heart, he thought, “I’ve lost. I admit defeat. Ok, I’ll help him scrub a little — nothing more.”

⭐️ Alright!!

From here, pages 298 - 310, the edits were so many but also so subtle that I can’t just write them in. Instead, I highly highly recommend that you read the translation done by @boat-full-of-lotus-pods :

Wherein we have a meltdown over just how filthy of a mouth Zhao Yunlan has in the Guardian webnovel, so like, reader beware I guess.

Moggiesandtea: I’m gonna be curious to see what ZYL calls Shen Wei after they’ve hooked up, since he’s been calling him his wife and variants thereof for 70 some chapters

Keep reading

MDZS Vol 5 Annotations 2

Part 2 of 6, pages 53 - 131

More annotations to help reading-flow! And another useless comment about another beautiful illustration.

JC is being disrespectful again, referring to LWJ as something akin to “that Lan guy.”

He is not talking to LWJ, but is instead complaining at Jin Ling.

More under the cut.

(Really? A GRE-vocab word here, where everything else is common-usage words?)

Yah… JGY isn’t supposed to have a right hand anymore by the time of this illustration…

As if LWJ would ever “call out” to anyone under less-than dire circumstances.

MDZS Masterlist.

All the Books I'm Annotating Masterlist.

Still trying to figure out why I like this look so much…

Would you be willing to talk about how standards of masculinity and femininity in Asia differ from those in Europe/North America? I know, it's a ridiculously broad question but I think you mentioned it in passing previously and I would be really interested in your answer especially in the context of the music industry and idols. I (European) sometimes see male Asian idols as quite feminine (in appearance, maybe?) even if they publicly talk about typically masculine hobbies of theirs.

Hi Anon,

Sorry that it took me over a month to get to this question, but the sheer volume of research that is necessary to actually answer this is significant, as there is an enormous body of work in gender studies. There are academics who have staked their entire careers in this field of research, much of which isn’t actually transnational, being that regional gender studies alone is already an incredibly enormous field.

As such, in no way can I say that I’ve been able to delve into even 1% of all the research that is out there to properly address this question. While I can talk about gender issues in the United States, and gender issues that deal with Asian American identity, I am not an expert in transnational gender studies between Asia and Europe. That being said, I’ll do my best to answer what I can.

When we consider the concept of “masculinity” and “femininity,” we must first begin with the fundamental understanding that gender is both a construct and a performance. The myth of gender essentialism and of gender as a binary is a product of patriarchy and compulsory heterosexuality in each culture where it emerges.

What you must remember when you talk about gendered concepts such as “masculinity” and “femininity” is that there is no universal idea of “masculinity” or “femininity” that speaks across time and nation and culture. Even within specific regions, such as Asia, not only does each country have its own understanding of gender and national signifiers and norms that defines “femininity” or “masculinity,” but even within the borders of the nation-state itself, we can find significantly different discourses on femininity and masculinity that sometimes are in direct opposition with one another.

If we talk about the United States, for example, can we really say that there is a universal American idea of “masculinity” or “femininity”? How do we define a man, if what we understand to be a man is just a body that performs gender? What kind of signifiers are needed for such a performance? Is it Chris Evan’s Captain America? Or is it Chris Hemsworth’s Thor? What about Robert Downey Jr.’s Tony Stark? Do these characters form a single, cohesive idea of masculinity?

What about Ezra Miller’s Barry Allen? Miller is nonbinary - does their superhero status make them more masculine? Or are they less “masculine” because they are nonbinary?

Judith Butler tells us in Gender Trouble (1990) and Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex” (1993) that what we call gender is inherently a discursive performance of specific signifiers and behaviors that were assigned to the gender binary and enforced by compulsory heterosexuality. She writes:

Insofar as heterosexual gender norms produce inapproximate ideals, heterosexuality can be said to operate through the regulated production of hyperbolic versions of “man” and “woman.” These are for the most part compulsory performances, ones which none of us choose, but which each of us is forced to negotiate. (1993: 237)

Because gender norms vary regionally, there are no stable norms that coalesce into the idea of a single, universal American “masculinity.” What I mean by this is that your idea of what reads as “masculine” might not be what I personally consider to be “masculine,” as someone who grew up in a very left-leaning liberal cosmopolitan area of the United States.

What I am saying is this: Anon, I think you should consider challenging your idea of gender, because it sounds to me like you have a very regionally locked conception of the gender binary that informs your understanding of “masculinity” and femininity” - an understanding that simply does not exist in Asia, where there is not one, but many different forms of masculinity.

China, Japan, and South Korea all have significant cultural differences and understandings of gender, which has a direct relationship with one’s national and cultural identity.

Japan, for example, might consider an idol who has long, layered hair and a thin body to be the ideal for idol masculinity, but would not consider an idol to be representative of “real” Japanese masculinity, which is epitomized by the Japanese salaryman.

South Korea, however, has a very specific idea of what idol masculinity must look like - simultaneously hypermasculine (i.e. extremely muscular, chiseled body) and “feminine” (i.e. makeup and dyed hair, extravagant clothing with a soft, beautiful face.) But South Korea also presents us with a more “standardized” idea of masculinity that offers an alternative to the “flowerboy” masculinity performed by idols, when we consider actors such as Hyun Bin and Lee Min-ho.

China is a little more complex. In order to understand Chinese masculinity, we must first understand that prior to the Hallyu wave, the idea of the perfect Chinese man was defined by three qualities: 高富帅 (gaofushuai) tall, moneyed, and handsome - largely due to the emergence of the Chinese metrosexual.

According to Kam Louie:

[The] Chinese metrosexual, though urbanized, is quite different from his Western counterpart. There are several translations of the term in Chinese, two of the most common and standard being “bailing li'nan” 白领丽男 and “dushili'nan” 都市丽男,literally “white-collar beautiful man” and “city beautiful man.” The notion of “beautiful man” (li-nan) refers to one who looks after his appearance and has healthy habits and all of the qualities usually attributed to the metrosexual; these are also the attributes of the reconstituted “cool” salaryman in Japan, men who have abandoned the “salaryman warrior” image and imbibed recent transnational corporate ideologies and practices.

[...]

In fact, the concept of the metrosexual by its very nature defines a masculinity ideal that can only be attained by the moneyed classes. While it can be said to be a “softer” image than the macho male, it nevertheless encompasses a very “hard” and competitive core, one that is more aligned with the traditional “wen” part of the wen-wu dyad that I put forward as a conventional Chinese ideal and the “salaryman warrior” icon in Japan. Unsurprisingly, both metrosexuality and wen-wu masculinity are created and embraced by men who are “winners” in the patriarchal framework.

The wen-wu 文武 (cultural attainment – martial valor) dyad that Louie refers to is the idea that Chinese masculinity was traditionally shaped by “a dichotomy between cultural and martial accomplishments” and is not only an ideal that has defined Chinese masculinity throughout history, but is also a uniquely Chinese phenomenon.

When the Hallyu wave swept through China, in an effort to capture and maximize success in the Chinese market, South Korean idol companies recruited Chinese idols and mixed them into their groups. Idols such as Kris Wu, Han Geng, Jackson Wang, and Wang Yibo are just a few such idols whose masculinities were redefined by the Kpop idol ideal.

Once that crossover occurred, China’s idol image shifted towards the example South Korea set, with one caveat: such an example can only exist on stage, in music videos, and other “idol” products. Indeed, if we look at any brand campaigns featuring Wang Yibo, his image is decisively more metrosexual than idol; he is usually shot bare-faced and clean-cut, without the “idol” aesthetics that dominate his identity as Idol Wang Yibo. But, this meterosexual image, despite being the epitome of Chinese idealized masculinity, would still be viewed as more “feminine” when viewed by a North American gaze. (It is important to note that this gaze is uniquely North American, because meterosexual masculinity is actually also a European ideal!)

The North American gaze has been trained to view alternate forms of masculinity as non-masculine. We are inundated by countless images of hypermasculinity and hypersexual femininity in the media, which shapes our cultural consciousness and understanding of gender and sexuality and unattainable ideals.

It is important to be aware that these ideals are culturally and regionally codified and are not universal. It is also important to challenge these ideals, as you must ask yourself: why is it an ideal? Why must masculinity be defined in such a way in North America? Why does the North American gaze view an Asian male idol and immediately read femininity in his bodily performance? What does that say about your North American cultural consciousness and understanding of gender?

I encourage you to challenge these ideas, Anon.

“Always already a cultural sign, the body sets limits to the imaginary meanings that it occasions, but is never free of imaginary construction.” - Judith Butler

Works Cited

Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble. New York, NY, Routledge, 1990. Butler, Judith. Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex. New York, NY, Routledge, 1993. Flowerboys and the appeal of 'soft masculinity' in South Korea. BBC, 2018, Louie, Kam. “Popular Culture and Masculinity Ideals in East Asia, with Special Reference to China.” The Journal of Asian Studies, Volume 71, Issue 4, November 2012 , pp. 929 - 943 Louie, Kam. Chinese, Japanese, and Global Masculine Identities. New York, NY, Routledge, 2003.

Chinese 🤦🏻♀️

Just this once, I wish they had not simplified a character. I keep mixing up the words for “old friend” vs “enemy”.

Like, really? One stroke difference?

Friends are old 古 but you want to…lick your enemy 舌?

I feel like I am under attack here...he certainly killed me...no question

-

sisterpaw125 liked this · 2 weeks ago

sisterpaw125 liked this · 2 weeks ago -

knight-tracer liked this · 2 weeks ago

knight-tracer liked this · 2 weeks ago -

cha0ticf0x liked this · 2 weeks ago

cha0ticf0x liked this · 2 weeks ago -

trypo-p liked this · 2 weeks ago

trypo-p liked this · 2 weeks ago -

slow-motion-shadow reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

slow-motion-shadow reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

todayiwrotenothing liked this · 2 weeks ago

todayiwrotenothing liked this · 2 weeks ago -

thurio-edau liked this · 2 weeks ago

thurio-edau liked this · 2 weeks ago -

sodascreen reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

sodascreen reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

sodascreen liked this · 2 weeks ago

sodascreen liked this · 2 weeks ago -

salty-spaceship reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

salty-spaceship reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

weepingfireflies liked this · 2 weeks ago

weepingfireflies liked this · 2 weeks ago -

almaluna liked this · 2 weeks ago

almaluna liked this · 2 weeks ago -

winterequinoxx liked this · 2 weeks ago

winterequinoxx liked this · 2 weeks ago -

wiley-treehouse-gardens liked this · 2 weeks ago

wiley-treehouse-gardens liked this · 2 weeks ago -

salty-spaceship liked this · 2 weeks ago

salty-spaceship liked this · 2 weeks ago -

lady-writes reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

lady-writes reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

faschionism reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

faschionism reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

dew-and-the-rope reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

dew-and-the-rope reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

atradi liked this · 2 weeks ago

atradi liked this · 2 weeks ago -

backupofgenosnumberonesimp liked this · 2 weeks ago

backupofgenosnumberonesimp liked this · 2 weeks ago -

imajourneyman reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

imajourneyman reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

tpytyg liked this · 2 weeks ago

tpytyg liked this · 2 weeks ago -

skysides reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

skysides reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

max-tothe-imum liked this · 2 weeks ago

max-tothe-imum liked this · 2 weeks ago -

amatus-lavellan reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

amatus-lavellan reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

empyrean-mangosteen liked this · 2 weeks ago

empyrean-mangosteen liked this · 2 weeks ago -

nihil-art liked this · 2 weeks ago

nihil-art liked this · 2 weeks ago -

darkshidori48 liked this · 2 weeks ago

darkshidori48 liked this · 2 weeks ago -

erodri reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

erodri reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

sleepiey liked this · 3 weeks ago

sleepiey liked this · 3 weeks ago -

sillyartisanvoid liked this · 3 weeks ago

sillyartisanvoid liked this · 3 weeks ago -

pagunonioi liked this · 3 weeks ago

pagunonioi liked this · 3 weeks ago -

lyne-333 liked this · 3 weeks ago

lyne-333 liked this · 3 weeks ago -

assi9 reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

assi9 reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

mega-layla-ex liked this · 3 weeks ago

mega-layla-ex liked this · 3 weeks ago -

ellasinnombre reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

ellasinnombre reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

lots-of-little-pink-clouds reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

lots-of-little-pink-clouds reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

crustysoapbubbles reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

crustysoapbubbles reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

crustysoapbubbles liked this · 3 weeks ago

crustysoapbubbles liked this · 3 weeks ago -

learlir reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

learlir reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

narwhalslikessprinkles reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

narwhalslikessprinkles reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

handmedownpocketpussy reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

handmedownpocketpussy reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

tinymarli liked this · 3 weeks ago

tinymarli liked this · 3 weeks ago -

kaijuatemyartblog reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

kaijuatemyartblog reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

kaijuatemyparents reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

kaijuatemyparents reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

astralwashboard reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

astralwashboard reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

chaoticgremlinmakingart liked this · 3 weeks ago

chaoticgremlinmakingart liked this · 3 weeks ago -

vinesandbones liked this · 3 weeks ago

vinesandbones liked this · 3 weeks ago -

sharkenthusiast liked this · 3 weeks ago

sharkenthusiast liked this · 3 weeks ago -

ediblenapkin-official reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

ediblenapkin-official reblogged this · 3 weeks ago