MDZS Vol 5 Annotations 2

MDZS Vol 5 Annotations 2

Part 2 of 6, pages 53 - 131

More annotations to help reading-flow! And another useless comment about another beautiful illustration.

JC is being disrespectful again, referring to LWJ as something akin to “that Lan guy.”

He is not talking to LWJ, but is instead complaining at Jin Ling.

More under the cut.

(Really? A GRE-vocab word here, where everything else is common-usage words?)

Yah… JGY isn’t supposed to have a right hand anymore by the time of this illustration…

As if LWJ would ever “call out” to anyone under less-than dire circumstances.

MDZS Masterlist.

All the Books I'm Annotating Masterlist.

More Posts from Weishenmewwx and Others

Stars of Chaos 杀破狼

Vol 2, Notes 4, pages 90 - 144.

Ten more pictures with notes about the novel! More text that may have been edited out of the print version!

Half of the sentence is gone!!!!!

"...and Chang Geng at that time had not even known what luxury and riches were, but had unexpectedly and resolutely left the marquis's residence; he would rather wander the wide 江湖 Jiang Hu than return to being a 'frog in a well' rich prince."

"Frog in a well" is 井底之蛙, which means "very limited worldview" since frogs in wells can't see more than their tiny patch of sky.

There is no mention of bloodlust in the version I read. It was just "In previous years, Gu Yun still frequently muttered about beating up this person or beating up that person..."

Yah. Priest has LOTS of plot. Constant bouncing between what happens in the imperial court vs in the outside-the-official-government world.

"粘". Priest even put that word in " ". It can mean sticky, adhesive. Not like a clingy girlfriend, more like magnets or glue.

It's very romantic right here, anyway. :)

Text, plus my bad handwriting: "Who knows what my brothers and comrades will think when they hear the news! What do you think, Marshal!?" meaning "What do you feel in your heart?! Do you really think this is fair?"

停 can mean "parked" or "landed," which I think makes more sense here since "stored" has the implication that the hawks are packed away, but, in this case, the hawks were flying just a little bit ago and now they are "landed," or "parked."

There some additional sentences in the version used for translation, I guess.

The Chinese from the version I read: 我若说出傅志诚私运紫流金谋反一事...

My bad translation: If I speak about Fu Zhicheng's smuggling Violet Gold conspiracy this one matter...

My interpretation: "the treason of smuggling violet gold," since he is referring to one matter, not two.

But it would not be weird if Priest later edited it into two matters of treason, one of smuggling and another of rebellion.

Chang Geng is elegant and graceful. He does not hunker. He settles.

炼丹 ”Make pills of immortality"

This "alchemy", Chinese version, is not to turn whatever into gold, but instead to find ways to extend your life; like how my mom puts turmeric in absolutely everything and reminds me to eat more blueberries and tomatoes and goji berries and...

OK! That's it for these ten photos! More later :)

My DanMei Literary Adventure Masterpost

Stars of Chaos - All Notes Links

Bookshelf inserts

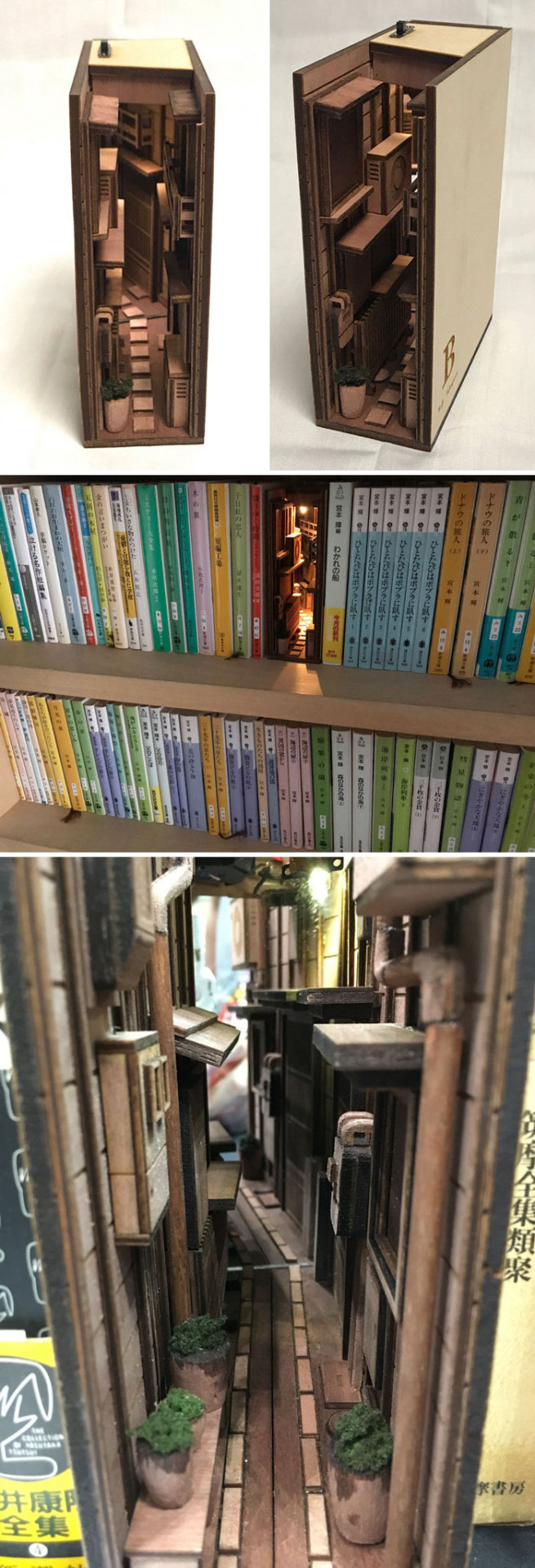

hey say that you can’t judge a book by its cover. But what if the cover alone can tell you the whole story? Welcome to the world of book nooks where creativity runs wild!

These hand-made creations will draw you into tiny places of wonder: from the hobbit hole to the Blade Runner-inspired apocalyptic alley or Lord of the Rings-themed door replica equipped with motion sensors.

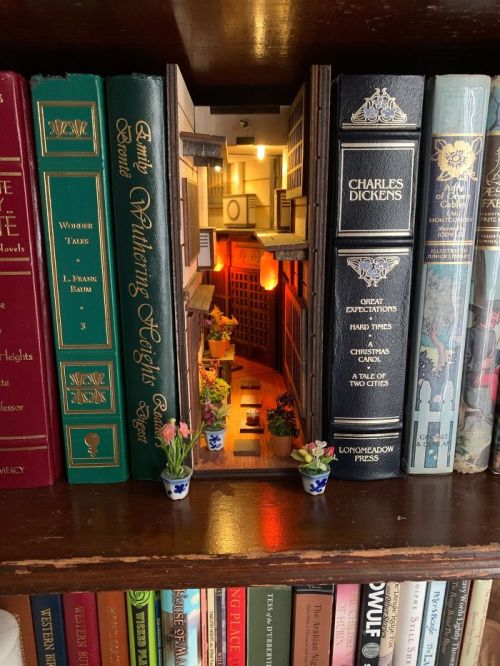

This book nook my mother got on Ebay

A Magical bookshop in your own bookshelf

I made a booknook for a christmas gift, my inspiration was Blade Runner. It’s 11" X 6"

Not only are book nook inserts a fun way to train your creativity muscle, they can also be a solution to making reading great again. A recent study done by Pew Research Center showed that a staggering quarter of American adults don’t read books in any shape or form. The same study suggested that the likelihood of reading was directly linked to wealth and educational level. Add high levels of modern insomnia and full-time employment that leaves many of us drained at the end of the day, and the idea of opening a book seems unappealing, to say the least.

Now imagine yourself walking past a bookshelf full of these mini worlds—the dioramas of an alley. They catch your attention and you cannot help but see what’s inside. The pioneer of the book nook concept is the Japanese artist Monde. Monde introduced his creations to the Design Festa in 2018 and received overwhelming feedback. 178K likes on twitter later, Monde has become an inspiration to the aspiring arts and crafts lovers who join on r/booknooks to share their spectacular ideas.

Hobbit Hole

Design, print and paint a small shelf to decorate shelves

worlds hidden in a bookcase

A double wide endor inspired wilderness piece

Old Italy book nook

Diagon Alley booknook

Witch is watching you

Warhammer-style booknook

Creature from the Black Lagoon bookshelf monster

A booknook inspired by Les Miserables

source https://www.boredpanda.com/book-nook-shelf-inserts

I love this so much, thank you!😊❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️

Please can you explain the difference of meaning between hanfu and huafu ? Sorry if you already got the question

Hi, thanks for the question, and sorry for taking ages to reply! (hanfu photo via)

The term “hanfu” (traditional Chinese: 漢服, simplified Chinese: 汉服) literally means “Han clothing”, and refers to the traditional clothing of the Han Chinese people. “Han” (漢/汉) here refers to the Han Chinese ethnic group (not the Han dynasty), and “fu” (服) means “clothing”. As I explained in this post, the modern meaning of “hanfu” is defined by the hanfu revival movement and community. As such, there is a lot of gatekeeping by the community around what is or isn’t hanfu (based on historical circumstances, cultural influences, tailoring & construction, etc). This isn’t a bad thing - in fact, I think gatekeeping to a certain extent is helpful and necessary when it comes to reviving and defining historical/traditional clothing. However, this also led to the need for a similarly short, catchy term that would include all Chinese clothing that didn’t fit the modern definition of hanfu -- enter huafu.

The term “huafu” (traditional Chinese: 華服, simplified Chinese: 华服) as it is used today has a broader definition than hanfu. “Hua” (華/华) refers to the Chinese people (中华民族/zhonghua minzu), and again “fu” (服) means “clothing”. It is an umbrella term for all clothing that is related to Chinese history and/or culture. Thus all hanfu is huafu, but not all huafu is hanfu. Below are examples of Chinese clothing that are generally not considered hanfu by the hanfu community for various reasons, but are considered huafu:

1. Most fashions that originated during the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), especially late Qing, including the Qing aoqun & aoku for women, and the Qing changshan and magua for men. I wrote about whether Qing dynasty clothing can be considered hanfu here. Tangzhuang, which is an updated form of the Qing magua popularized in 2001, can also fit into this category. Below - garments in the style of Han women’s clothing during the Qing dynasty (清汉女装) from 秦綿衣莊 (1, 2).

2. Fashions that originated during the Republican era/minguo (1912-1949), including the minguo aoqun & aoku and qipao/cheongsam for women, and the minguo changshan for men (the male equivalent of the women’s qipao). I wrote about why qipao isn’t considered hanfu here. Below - minguo aoqun (left) & qipao (right) from 嬉姷.

Below - Xiangsheng (crosstalk) performers Zhang Yunlei (left) & Guo Qilin (right) in minguo-style men’s changshan (x). Changshan is also known as changpao and dagua.

3. Qungua/裙褂 and xiuhefu/秀禾服, two types of Chinese wedding garments for brides that are commonly worn today. Qungua originated in the 18th century during the Qing dynasty, and xiuhefu is a modern recreation of Qing wedding dress popularized in 2001 (x). Below - left: qungua (x), right: xiuhefu (x).

4. Modified hanfu (改良汉服/gailiang hanfu) and hanyuansu/汉元素 (hanfu-inspired fashion), which do not fit in the orthodox view of hanfu. Hanfu mixed with sartorial elements of other cultures also fit into this category (e.g. hanfu lolita). From the very start of the hanfu movement, there’s been debate between hanfu “traditionalists” and “reformists”, with most members being somewhere in the middle, and this discussion continues today. Below - hanyuansu outfits from 川黛 (left) and 远山乔 (right).

5. Performance costumes, such as Chinese opera costumes (戏服/xifu) and Chinese dance costumes. These costumes may or may not be considered hanfu depending on the specific style. Dance costumes, in particular, may have non-traditional alterations to make the garment easier to dance in. Dunhuang-style feitian (apsara) costumes, which I wrote about here, can also fit into this category. Below - left: Chinese opera costume (x), right: Chinese dance costume (x).

6. Period drama costumes and fantasy costumes in popular media (live-action & animation, games, etc.), commonly referred to as guzhuang/古装 (lit. “ancient costumes”). Chinese period drama costumes are of course based on hanfu, and may be considered hanfu if they are historically accurate enough. However, as I wrote about here, a lot of the time there are stylistic inaccuracies (some accidental, some intentional) that have become popularized and standardized over time (though this does seem to be improving in recent years). This is especially prevalent in the wuxia and xianxia genres. Similarly, animated shows & games often have characters dressed in “fantasy hanfu” that are essentially hanfu with stylistic modifications. Below - left: Princess Taiping in historical cdrama 大明宫词/Palace of Desire (x), right: Wei Wuxian and Lan Wangji in wuxia/xianxia cdrama 陈情令/The Untamed (x).

7. Any clothing in general that purposefully utilizes Chinese style elements (embroidery, fabrics, patterns, motifs, etc). Chinese fashion brand Heaven Gaia is a well-known example of this. Below - Chinese-inspired designs by Heaven Gaia (x).

8. Technically, the clothing of China’s ethnic minorities also fit under the broad definition of huafu, but it’s rarely ever used in this way.

From personal observation, the term “huafu” is mainly used in the following situations:

1. Some large-scale events to promote Chinese clothing, such as the annual “华服日/Huafu Day”, will use “huafu” in their name for inclusivity.

2. For the same reason as above, Chinese clothing including hanfu will often be referred to as “huafu” on network television programs (ex: variety shows).

3. A few Chinese clothing shops on Taobao use “huafu” in their shop name. Two examples:

明镜华服/Mingjing Huafu - sells hanfu & hanyuansu.

花神妙华服/Huashenmiao Huafu - sells Qing dynasty-style clothing.

With the exception of the above, “huafu” is still very rarely used, especially compared to “hanfu”. It has such a broad definition that it’s just not needed in situations for which a more precise term already exists. However, I do think it’s useful as a short catch-all term for Chinese clothing that isn’t limited to the currently accepted definition of hanfu.

If anyone wants to add on or correct something, please feel free to do so! ^^

Hope this helps!

二哈和他的白猫师尊 The Husky and His White Cat ShiZun

Book Annotations

I feel like this translation is great. It's smooth and easy to read, and I feel like it conveys the story really well.

As I prepare to hand this book over to my non-Chinese friends, I do have a few notes, though.

How to pronounce people's names.

Usage of the word "Master" vs "Teacher"

Book 1

Pages 1-182

Pages 185-end

Book 2

Pages 1-132

Pages 137-198

Pages 208-327

Pages 366-end

Book 3

Pages 1-end

Book 4

Pages 1-end

I’m looking forward to this (badly suppressed excitement I’m about to text this trailer to Everyone i know. Michelle Yeoh is and always has been a superhero!!!!!)

Everything Everywhere All At Once | A24

Starring Michelle Yeoh

Stars of Chaos 杀破狼

Volume 3, Notes 5/5, Pages 358 - end

The "Imperial Censorate" here is 御史台, which is the department, not the person. Chang Geng would never slap another person in full view of the court; but he would not hesitate to admistratively slap another department if he felt it was justified.

So. The classic punishment for adultery was to be put in a pig cage and thrown into the river to drown. I don't know how I know this little bit of trivia, seeing as I was raised in the west and my only contact to Chinese culture was my very conservative Chinese mother; but I know this. Adulterers get drowned.

谋事在人,成事在天。 Plotting depends the person, success depends on the heavens. I just wanted you to know that it's symmetrical in Chinese, even though it doesn't translate that way.

The "tactlessly" here is a translation of 不长眼色, which I think could be explained better as "not reading the room" or "not taking hints."

It's not that Ge Chen is tactless so much as he is clueless to the tension between Gu Yun and Chang Geng.

In the online Chinese version that I read, the line is "Zixi! Don't go!" which explains why Chang Geng is reaching out to grab him in a panic -- he thinks Gu Yun is leaving him.

Page 382

Top: The Chinese here is "看看我说话!" which can be translated as either

-- "Look at me while I am talking to you," (though that feels weird) or -- "Look at me and speak - respond to me,"

...both of which are a little different from what is actually written in English. The "look at me when you speak" translation threw me for a second because Chang Geng isn't speaking and hasn't said anything for a while.

Bottom: Liangjiang is 两江 which is Two Rivers. (The north side and the south side of the river?)

This section is actually so pretty:

“天时地利、花前月下、水到渠成”

The perfect time (天时) and place (地利); in front of the flowers (花前) and under the moon (月下); when success is assured (where water flows (水到) a canal will inevitably form (渠成)).

Carriage Door. The carriage door opened, and out came Shen Yi. He had hitched a ride with Miss Chen so that he could leave his home unnoticed.

(When I read the English, I thought that the door was the courtyard door and got really confused.)

----

And that's it for Volume 3!

I love 杀破狼 <3

My DanMei Literary Adventure Masterpost

Stars of Chaos - All Notes Links

WangXian Phoenix Mountain Kiss Censored Panels?

Ok I don't know how official this is...if it's like that "leak" of WangXian's drunk kiss or just a really really good fanart, but these're SUPPOSEDLY the missing panels from WangXian's Phoenix Mountain kiss in chap 185 of the manhua that were chopped due to good old censorship.

It's so weird cuz I just read another danmei manhua that had their kiss intact and they even kinda showed a nonexplicit handjob, so if these are indeed official, I wish they wouldn't be so hard on MDZS.

~

credit to weibo in last image above.

Concept arts and sample insert illustrations by Marina Privalova (@Baoshan_Karo) for Sha Po Lang Russian Edition of the book shared by Istari Comics Publishing.

If you haven't seen the beautiful cover arts, here's the link.

Yes, the same artist behind MDZS insert illustrations for EN and RUS license.

WHEN SANITY IS NOT HOME

Starring: DaGe, Director Nie, ErGe, and Yaomei.

Sorry, I can't breathe👻

The 36 Stratagems in mdzs

🔮 I describe individual scenes in MDZS where each of the 36 Stratagems plays out

🔮 Note that while this post mainly references novel canon, it may wander into CQL territory at times

🔮 I won’t include the detailed history of each of the Stratagems in this meta as they may be too long, but I will include a resource at the end that you can refer to for further reading

🔮 Spoilers ahead!

Let’s go!

Ok so! The 36 Stratagems (三十六计) is an essay on the use of cunning ruses and deceptive tactics on the battlefield, in politics, and in civil matters. It has been attributed to various authors throughout popular history, and references various famous military scenarios in the Warring States era (战国时代) and Three Kingdoms period (三国时代).

The 36 Stratagems are split into six discrete sections, each describing six techniques:

胜战计: victory stratagems

敌战计: enemy fighting stratagems

攻战计: attack stratagems

混战计: chaos stratagems

并战计: proximate (parallel) stratagems

败战计: desperate stratagems

胜战计 Victory stratagems

1. 瞒天过海: crossing the sea without alerting the heavens; i.e. setting a fake objective to mislead others, while concealing progress for the true objective.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Wei Wuxian taking a blindfolded Jiang Cheng to “visit Baoshan Sanren” to “get his core repaired”. This was a ruse to conceal the true objective — a core transfer.

2. 围魏救赵: besieging Wei to rescue Zhao (Wei and Zhao were states in the Warring States period); i.e. attacking something precious to the enemy to avoid a head-on battle and forcing them to retreat.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Jin Guangyao placing a qin string around Wei Wuxian’s neck to force Lan Wangji to stand down at the Guanyin temple.

Bonus: Jin Guangyao is literally “besieging Wei/围魏” here! The word 围, other than “to besiege”, also means “to encircle” or “to surround”.

3. 借刀杀人: killing with a borrowed blade; i.e. outsourcing a difficult or incriminating task to someone else.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Nie Huaisang instigating Lan Xichen to stab Jin Guangyao in the Guanyin temple. Quite literally, he “borrows” Lan Xichen’s sword to do the deed.

4. 以逸待劳: letting others exhaust themselves, and swooping in at the right moment to claim victory or deal the final blow.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Wen Chao instructing the hostages from the various clans to wear the Xuanwu down, with the intention of coming in at the last minute to claim the kill.

5. 趁火打劫: looting a burning house; i.e. taking advantage of a desperate situation to raid a weakened enemy.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Qishan Wen taking advantage of Jiang Fengmian’s absence to launch an attack on Lotus Pier.

6. 声东击西: making a sound in the east to misdirect the enemy, while striking in the west.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Jin Guangyao instigating the second siege of the Burial Mounds to divert everyone’s attention, whilst simultaneously making preparations for his escape to Dongying.

敌战计 Enemy fighting stratagems

7. 无中生有: creating something out of nothing; i.e. creating an illusion or lie to fool people into believing something exists.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Nie Huaisang perpetuating the rumor that his family’s ancestral tomb is actually a man-eating fortress, to prevent grave robbers from entering it.

8. 暗渡陈仓: sneaking through the passage of Chencang while repairing the main roads; i.e. distracting the enemy while taking a shortcut to launch an attack.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Su She devising a similar-sounding qin score to that of Gusu Lan. The discordant notes distracted the Lan disciples, concealing the score’s true purpose — weakening people’s spiritual abilities.

9. 隔岸观火: watching the fire from the opposite bank; i.e. delaying entering a battle until the enemy has been weakened, then moving in at full strength.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Xue Yang slowly chipping away at Xiao Xingchen’s virtue by making him kill innocent people, then revealing the truth at the end to break him.

10. 笑里藏刀: hiding a knife behind a smile: i.e. putting up a friendly appearance to conceal one’s true intentions.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Jin Guangyao’s political maneuvering to make himself seem genial and unassuming, while concealing the truth about his roles in Nie Mingjue’s and Jin Guangshan’s deaths.

11. 李代桃僵: sacrificing the plum tree for the peach tree; i.e. sacrificing some short-term aims for a greater, long-term good.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Wei Wuxian accepting the eventuality of Wang Lingjiao chopping off his hand, and later, sacrificing his own core to restore Jiang Cheng and preserve the Jiang clan in the long run.

12. 顺手牵羊: taking a opportunity to steal a goat; i.e. making use of available resources as they present themselves.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Wei Wuxian leading Lil Apple from the Mo household!

攻战计 Attack stratagems

13. 打草惊蛇: hitting the grass to startle the snake; i.e. making over-the-top gestures to taunt or disrupt the enemy.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Wei Wuxian taunting Wen Chao in the Xuanwu cave for his lack of knowledge of Wen Mao’s writings, to lure Wen Chao away from Wen Zhuliu’s protection.

14. 借尸还魂: borrowing a corpse to resurrect a soul; i.e. fixing up something useless to give it a fresh purpose.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Mo Xuanyu’s body literally being used as a vessel to resurrect Wei Wuxian!

Bonus: here’s a short explanation I previously wrote as part of the cql subs critique for Episode 1 on the poem Chu Ci 楚辞. It’s in para 4.

15. 调虎离山: enticing the tiger to leave the mountain; i.e. luring a strong enemy away from their base of protection to attack them in the open.

Where this plays out in MDZS: the invitation to Jin Ling’s party as a means to lure Wei Wuxian from Burial Mounds and into a set-up.

16. 欲擒故纵: loosening the hold slightly to ensure capture; i.e. allowing an enemy to believe they have a chance to escape, thus getting them to lower their defenses, then crushing their morale.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Wei Wuxian taunting Wen Chao at various intervals instead of killing him outright — letting Wen Chao run a little, then catching up with him to slice pieces off of his body.

17. 抛砖引玉: tossing pieces of brick to get gems; i.e. throwing out pieces of useless information to tempt the enemy into revealing something important.

Where this plays out in MDZS: A-Qing deliberately misinterpreting the term “night-hunt 夜猎” to trick Xue Yang into revealing that he is also a cultivator.

18. 擒贼擒王: defeating the enemy by first defeating their leader.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Nie Mingjue infiltrating Nightless City during the Sunshot Campaign to attack Wen Ruohan, as a means of quickly securing victory.

混战计 Chaos stratagems

19. 釜底抽薪: removing the firewood from the underside of the pot; i.e. cutting off an enemy’s resources or means of attack.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Jin Guangyao making everyone seal their spiritual powers in Guanyin temple, so they would not be able to attack him.

20. 浑水摸鱼: disturbing the water to catch the fish; i.e creating confusion to mask one’s true purpose.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Su She trying to incite mass panic during the second siege of Burial Mounds to get everyone to be suspicious of Wei Wuxian.

21. 金蝉脱壳: the golden cicada shedding its shell; i.e. leaving riches or identifying marks behind to go undercover or escape.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Jin Guangyao, knowing that he has incurred the ire of the clans, preparing to leave his position behind and escape to Dongying.

22. 关门捉贼: shutting the door to catch a thief; i.e. cutting off all escape routes for an enemy.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Xue Yang trapping the juniors in Yi City and turning them around in circles, in order to get close to Wei Wuxian.

23. 远交近攻: allying with people further away while attacking those closest, for a strategic advantage.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Jin Guangyao swearing brotherhood with the two most powerful people outside the Jin clan, whilst simultaneously planning his takeover of the Jin household.

Bonus: here’s another meta I wrote on Jin Guangyao’s personal reasons for joining the sworn brotherhood, in which I also touch on 远交近攻.

24. 假途伐虢: getting safe passage to besiege Guo (a state during the Zhou dynasty); i.e. borrowing an ally’s resources to attack an enemy, then turning on that same ally with those resources.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Xue Yang borrowing the abilities of Shuanghua to kill innocent people, then instigating Xiao Xingchen to turn those same abilities on Song Lan, thus destroying their bond.

并战计 Proximate stratagems

25. 偷梁换柱: replacing the beams with rotting timbers; i.e. disrupting the enemy’s operations by replacing certain supports with inferior varieties.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Jin Guangyao swapping the notes of Cleansing 洗华 with those from the Collection of Turmoil 乱魄抄.

Bonus: here’s a quick explanation on the name 乱魄抄 in my critique of CQL episode 42, para 441.

26. 指桑骂槐: pointing at the mulberry tree while cursing the locust tree; i.e. deliberately misdirecting one’s anger to avoid having to make the first move.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Jin Guangyao forcing Wei Wuxian to reveal himself in the treasure room by addressing him as Mo Xuanyu, accusing him of slander and of causing Qin Su’s death.

Bonus: it’s possible that Nie Huaisang’s name was derived from this particular stratagem — except that instead of the locust tree 槐, he uses the character 怀, which loosely means “to harbor (in one’s heart)”. Both words use the same tone and are similarly pronounced.

27. 假痴不颠: feigning ignorance to lure the enemy into complacency.

Where this plays out in MDZS: this is the crux of Nie Huaisang’s nickname, 一问三不知 “Mr I Don’t Know”!

Bonus: here’s a brief explanation I wrote about 一问三不知 for my critique of CQL episode 34, para 351.

28. 上屋抽梯: removing the ladder when the enemy has reached the roof; i.e. severing an enemy’s recourse or supply lines.

Where this plays out in MDZS: the plot for Su She to finish everyone off at the second siege of Burial Mounds, through the cutting off of everyone’s spiritual abilities and means of escape.

29. 树上开花: tying blossoms on a dead tree; i.e. making something of low value appear useful and beautiful through artifice.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Jin Guangshan accepting Jin Guangyao into the family and bestowing his own generational name on him as a public honor, while continuing to undermine and ill-treat him.

30. 反客为主: forcing the host and guest to change places; i.e. usurping authority by turning the tables.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Wei Wuxian seizing Wen Chao and holding him hostage in the Xuanwu cave.

败战计 Desperate stratagems

31. 美人计: the beauty trap; i.e. sending a beautiful woman to distract the enemy and incite unrest in their camp.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Jin Guangyao literally ensnaring his own father in such a fashion to bring about his death.

32. 空城计: the empty city; i.e. appearing calm despite being at a disadvantage, to fool the enemy into thinking that there is an ambush waiting for them.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Wei Wuxian remaining at ease when confronting Xue Yang in Yi City, despite knowing he would not be able to physically overpower him.

33. 反间计: sowing discord between an enemy and their allies.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Nie Huaisang instigating Bi Cao to write a letter to Qin Su, with the intent of turning her against Jin Guangyao.

34. 苦肉计: inflicting injury on oneself to earn the enemy’s trust and sympathy.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Xue Yang masquerading as an injured Xiao Xingchen to gain entry to the house that Wei Wuxian and the juniors were hiding in.

35. 连环计: chain stratagems; i.e. carrying out different plans as part of a linked, continuous scheme.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Nie Huaisang methodically laying the trail of body parts and clues for Wei Wuxian and Lan Wangji to follow.

36. 走为上: if all else fails, flee, and regroup to fight another day.

Where this plays out in MDZS: Wei Wuxian and Lan Wangji running from the Xuanwu after their escape had been sealed off.

Bonus: there’s a saying 三十六计 走为上计 which means “of all the 36 Stratagems, fleeing is the best”!

References

Translations largely referenced from Military Wikia

Details of each of the Stratagems

Original post on Twitter

-

lazyobject liked this · 9 months ago

lazyobject liked this · 9 months ago -

optimisticmiraclefest reblogged this · 9 months ago

optimisticmiraclefest reblogged this · 9 months ago -

optimisticmiraclefest liked this · 9 months ago

optimisticmiraclefest liked this · 9 months ago -

burritofromhell liked this · 10 months ago

burritofromhell liked this · 10 months ago -

oa-trance liked this · 1 year ago

oa-trance liked this · 1 year ago -

kaiscove liked this · 1 year ago

kaiscove liked this · 1 year ago -

fengshenjunlang liked this · 1 year ago

fengshenjunlang liked this · 1 year ago -

oatmealnebraska liked this · 1 year ago

oatmealnebraska liked this · 1 year ago -

wutheringskies liked this · 1 year ago

wutheringskies liked this · 1 year ago -

theblogyourmotherwarnedyouabout liked this · 1 year ago

theblogyourmotherwarnedyouabout liked this · 1 year ago -

aurorablackwei liked this · 1 year ago

aurorablackwei liked this · 1 year ago -

lanwangjiismyreligion liked this · 1 year ago

lanwangjiismyreligion liked this · 1 year ago -

nogenderonlyanxiety liked this · 1 year ago

nogenderonlyanxiety liked this · 1 year ago -

lirithsi liked this · 1 year ago

lirithsi liked this · 1 year ago -

mega-mathi liked this · 1 year ago

mega-mathi liked this · 1 year ago -

artemisisdiana reblogged this · 1 year ago

artemisisdiana reblogged this · 1 year ago -

grewlikefancyflowers reblogged this · 1 year ago

grewlikefancyflowers reblogged this · 1 year ago -

stabbythespaceroomba liked this · 1 year ago

stabbythespaceroomba liked this · 1 year ago -

shyobservationblog liked this · 1 year ago

shyobservationblog liked this · 1 year ago -

weishenmewwx reblogged this · 1 year ago

weishenmewwx reblogged this · 1 year ago