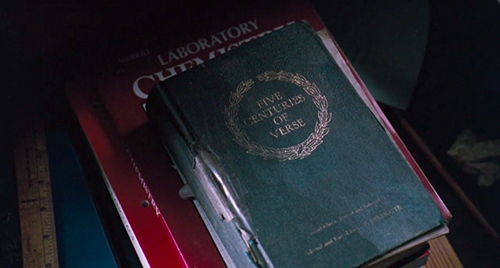

Dead Poets Society (1989)

Dead Poets Society (1989)

“We don’t read and write poetry because it’s cute. We read and write poetry because we are members of the human race. And the human race is filled with passion. And medicine, law, business, engineering, these are noble pursuits and necessary to sustain life. But poetry, beauty, romance, love, these are what we stay alive for.”

More Posts from Smparticle2 and Others

Snowflakes from William Scoresby’s des Jüngern Tagebuch einer reise auf den Wallfischfang, (Hamburg: F. Perthes, 1825), the German translation of Journal of a voyage to the northern whale-fishery.

Scoresby was an Arctic explorer with interests in meteorology and navigation, who led an Arctic exploration in the early 1800s to the area around Greenland.

Big Improvements to Brain-Computer Interface

When people suffer spinal cord injuries and lose mobility in their limbs, it’s a neural signal processing problem. The brain can still send clear electrical impulses and the limbs can still receive them, but the signal gets lost in the damaged spinal cord.

The Center for Sensorimotor Neural Engineering (CSNE)—a collaboration of San Diego State University with the University of Washington (UW) and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)—is working on an implantable brain chip that can record neural electrical signals and transmit them to receivers in the limb, bypassing the damage and restoring movement. Recently, these researchers described in a study published in the journal Nature Scientific Reports a critical improvement to the technology that could make it more durable, last longer in the body and transmit clearer, stronger signals.

The technology, known as a brain-computer interface, records and transmits signals through electrodes, which are tiny pieces of material that read signals from brain chemicals known as neurotransmitters. By recording brain signals at the moment a person intends to make some movement, the interface learns the relevant electrical signal pattern and can transmit that pattern to the limb’s nerves, or even to a prosthetic limb, restoring mobility and motor function.

The current state-of-the-art material for electrodes in these devices is thin-film platinum. The problem is that these electrodes can fracture and fall apart over time, said one of the study’s lead investigators, Sam Kassegne, deputy director for the CSNE at SDSU and a professor in the mechanical engineering department.

Kassegne and colleagues developed electrodes made out of glassy carbon, a form of carbon. This material is about 10 times smoother than granular thin-film platinum, meaning it corrodes less easily under electrical stimulation and lasts much longer than platinum or other metal electrodes.

“Glassy carbon is much more promising for reading signals directly from neurotransmitters,” Kassegne said. “You get about twice as much signal-to-noise. It’s a much clearer signal and easier to interpret.”

The glassy carbon electrodes are fabricated here on campus. The process involves patterning a liquid polymer into the correct shape, then heating it to 1000 degrees Celsius, causing it become glassy and electrically conductive. Once the electrodes are cooked and cooled, they are incorporated into chips that read and transmit signals from the brain and to the nerves.

Researchers in Kassegne’s lab are using these new and improved brain-computer interfaces to record neural signals both along the brain’s cortical surface and from inside the brain at the same time.

“If you record from deeper in the brain, you can record from single neurons,” said Elisa Castagnola, one of the researchers. “On the surface, you can record from clusters. This combination gives you a better understanding of the complex nature of brain signaling.”

A doctoral graduate student in Kassegne’s lab, Mieko Hirabayashi, is exploring a slightly different application of this technology. She’s working with rats to find out whether precisely calibrated electrical stimulation can cause new neural growth within the spinal cord. The hope is that this stimulation could encourage new neural cells to grow and replace damaged spinal cord tissue in humans. The new glassy carbon electrodes will allow her to stimulate, read the electrical signals of and detect the presence of neurotransmitters in the spinal cord better than ever before.

Golden Gate Bridge by Jason Jko

There is a time when it is necessary to abandon the used clothes, which already have the shape of our body and to forget our paths, which takes us always to the same places. This is the time to cross the river: and if we don’t dare to do it, we will have stayed, forever beneath ourselves

Fernando Pessoa (via paizleyrayz)

Theatre time. All dancer have their own ways of getting ready for a show. I believe that a consistent routine is important to preparing for what’s ahead in a few hours. Because Forsythe’s “Artifact” is so hard on the body and I’m in every show, I tend to get to the theatre pretty early to make sure everything is ready, to put on some “normatec” boots (a compression boot for athletes that helps greatly with fatigue) and do hair and makeup. - Lia Cirio

Lia Cirio - Boston Opera House

Follow the Ballerina Project on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, Twitter & Pinterest

For information on purchasing Ballerina Project limited edition prints.

:)

If you liked The Map of Physics animation, I bet you’ll like The Map of Mathematics too (also by Dominic Walliman):

h-t Open Culture

OSKI

Pop-Outs: How the Brain Extracts Meaning From Noise

UC Berkeley neuroscientists have now observed this re-tuning in action by recording directly from the surface of a person’s brain as the words of a previously unintelligible sentence suddenly pop out after the subject is told the meaning of the garbled speech. The re-tuning takes place within a second or less, they found.

The research is in Nature Communications. (full open access)

“You wanna appease me, compliment my brain!” -Christina Yang

Novel laminated nanostructure gives steel bone-like resistance to fracturing under repeated stress

Metal fatigue can lead to abrupt and sometimes catastrophic failures in parts that undergo repeated loading, or stress. It’s a major cause of failure in structural components of everything from aircraft and spacecraft to bridges and powerplants. As a result, such structures are typically built with wide safety margins that add to costs.

Now, a team of researchers at MIT and in Japan and Germany has found a way to greatly reduce the effects of fatigue by incorporating a laminated nanostructure into the steel. The layered structuring gives the steel a kind of bone-like resilience, allowing it to deform without allowing the spread of microcracks that can lead to fatigue failure.

The findings are described in a paper in the journal Science by C. Cem Tasan, the Thomas B. King Career Development Professor of Metallurgy at MIT; Meimei Wang, a postdoc in his group; and six others at Kyushu University in Japan and the Max Planck Institute in Germany.

“Loads on structural components tend to be cyclic,” Tasan says. For example, an airplane goes through repeated pressurization changes during every flight, and components of many devices repeatedly expand and contract due to heating and cooling cycles. While such effects typically are far below the kinds of loads that would cause metals to change shape permanently or fail immediately, they can cause the formation of microcracks, which over repeated cycles of stress spread a bit further and wider, ultimately creating enough of a weak area that the whole piece can fracture suddenly.

Read more.

-

lousylittleegos liked this · 4 months ago

lousylittleegos liked this · 4 months ago -

signs-of-sleep reblogged this · 4 months ago

signs-of-sleep reblogged this · 4 months ago -

signs-of-sleep liked this · 4 months ago

signs-of-sleep liked this · 4 months ago -

lesbiancharliedalton reblogged this · 1 year ago

lesbiancharliedalton reblogged this · 1 year ago -

lesbiancharliedalton liked this · 1 year ago

lesbiancharliedalton liked this · 1 year ago -

sickhotaew reblogged this · 1 year ago

sickhotaew reblogged this · 1 year ago -

mrsbright--side liked this · 1 year ago

mrsbright--side liked this · 1 year ago -

dumbvampyr liked this · 3 years ago

dumbvampyr liked this · 3 years ago -

arooomofmyown reblogged this · 3 years ago

arooomofmyown reblogged this · 3 years ago -

carnalreincarnated liked this · 3 years ago

carnalreincarnated liked this · 3 years ago -

itsageekhaven reblogged this · 3 years ago

itsageekhaven reblogged this · 3 years ago -

agentlemanstaste liked this · 3 years ago

agentlemanstaste liked this · 3 years ago -

ahomosapienworld liked this · 3 years ago

ahomosapienworld liked this · 3 years ago -

rawmp4 liked this · 3 years ago

rawmp4 liked this · 3 years ago -

fakecactusthumb liked this · 4 years ago

fakecactusthumb liked this · 4 years ago -

rcouls liked this · 4 years ago

rcouls liked this · 4 years ago -

queenmoriarty liked this · 4 years ago

queenmoriarty liked this · 4 years ago -

queenmoriarty reblogged this · 4 years ago

queenmoriarty reblogged this · 4 years ago -

questof-truth liked this · 4 years ago

questof-truth liked this · 4 years ago -

blurringperiphery liked this · 4 years ago

blurringperiphery liked this · 4 years ago -

teddypng reblogged this · 4 years ago

teddypng reblogged this · 4 years ago -

stuffkimlikes reblogged this · 4 years ago

stuffkimlikes reblogged this · 4 years ago -

stuffkimlikes liked this · 4 years ago

stuffkimlikes liked this · 4 years ago -

oopsabird liked this · 4 years ago

oopsabird liked this · 4 years ago -

dirkbogardes reblogged this · 4 years ago

dirkbogardes reblogged this · 4 years ago -

dirkbogardes liked this · 4 years ago

dirkbogardes liked this · 4 years ago -

ladymcfly97 liked this · 4 years ago

ladymcfly97 liked this · 4 years ago -

theamazingfeministunicorn liked this · 4 years ago

theamazingfeministunicorn liked this · 4 years ago -

sextusempiricus2 liked this · 4 years ago

sextusempiricus2 liked this · 4 years ago -

laprasloversassociation reblogged this · 4 years ago

laprasloversassociation reblogged this · 4 years ago -

dumbfuck-mojave liked this · 4 years ago

dumbfuck-mojave liked this · 4 years ago -

fobisnotonfire liked this · 4 years ago

fobisnotonfire liked this · 4 years ago -

the7thcrow liked this · 4 years ago

the7thcrow liked this · 4 years ago -

joursetfleurs liked this · 4 years ago

joursetfleurs liked this · 4 years ago -

startedfollowinme liked this · 4 years ago

startedfollowinme liked this · 4 years ago -

ao--tsuki liked this · 4 years ago

ao--tsuki liked this · 4 years ago -

horrorinthesunflowerfields liked this · 4 years ago

horrorinthesunflowerfields liked this · 4 years ago -

fuzzypsychicjudgesports liked this · 4 years ago

fuzzypsychicjudgesports liked this · 4 years ago -

67slennon liked this · 4 years ago

67slennon liked this · 4 years ago -

mostlyiwanttobekind reblogged this · 4 years ago

mostlyiwanttobekind reblogged this · 4 years ago -

silentheartsworld liked this · 4 years ago

silentheartsworld liked this · 4 years ago -

gul-balam reblogged this · 4 years ago

gul-balam reblogged this · 4 years ago