A Disturbance In The F-Ring

A Disturbance In The F-Ring

A bright disruption in Saturn’s narrow F ring suggests it may have been disturbed recently. This feature was mostly likely not caused by Pandora (50 miles or 81 kilometers across) which lurks nearby, at lower right. More likely, it was created by the interaction of a small object embedded in the ring itself and material in the core of the ring. Scientists sometimes refer to these features as “jets.”

Because these bodies are small and embedded in the F ring itself, they are difficult to spot at the resolution available to NASA’s Cassini spacecraft. Instead, their handiwork reveals their presence, and scientists use the Cassini spacecraft to study these stealthy sculptors of the F ring.

This view looks toward the sunlit side of the rings from about 15 above the ring plane. The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on April 8, 2016.

The view was acquired at a distance of approximately 1.4 million miles (2.2 million kilometers) from Saturn and at a Sun-Saturn-spacecraft, or phase, angle of 105 degrees. Image scale is 8 miles (13 kilometers) per pixel.

The Cassini mission is a cooperative project of NASA, ESA (the European Space Agency) and the Italian Space Agency. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the mission for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, Washington. The Cassini orbiter and its two onboard cameras were designed, developed and assembled at JPL. The imaging operations center is based at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colorado. -NASA/JPL-

Image above © NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

More Posts from Secretagentpeptidebond and Others

Also because of that whole "tests unproven research on himself without respect to lab safety protocol" thing

SCIENCE… TOO STRESSFUL FOR HULK… HULK NEED HUG…

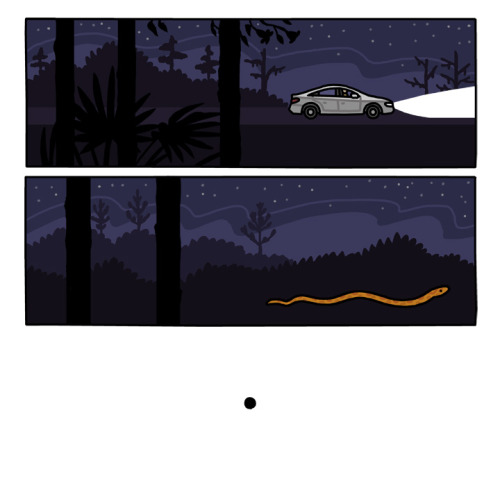

A snake story, based on an experience I had while I was in Florida.

Gases + Electric Field

Click on pictures for more information.

Source

SUPERSLIPPERY SIDE UP

These two steel balls sit in a pool of octane, a component of petroleum, that has been dyed yellow. Though the ball on the left has picked up streaks of the oily liquid, the ball on the right has repelled the octane thanks to a self-healing, superslippery coating called X-SLIPS. Researchers developed this coating, which repels both water and oil, based on the slippery interiors of Nepenthes pitcher plants and the wax layer on plant leaves. To make the coating, the team applied a 2.5- µm-thick layer of fluorinated silane to the sanded surface of the ball. A spritz of DuPont’s Krytox lubricant, a perfluorinated oil similar to Teflon, adheres tightly to the silane to create a surface that fends off water and oil. After damaging the coating with blasts of oxygen plasma or abuse with 40-grit sandpaper, the researchers could restore it by simply heating it, causing the remaining silane to redistribute across the surface and re-adhere. The coating could be useful on ships or in condiment packaging.

Credit: Tak-Sing Wong/ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, DOI: 10.1021/acsami.6b00194

Enter our photo contest here

Related C&EN content:

Materials Science For Athletes And Couch Potatoes

Superhero origin story

why hood 32?

Oooooh this is a good story! ( I think, at least). In my first summer of college I had a stockroom job in the chem department. My friend Annie and I were tasked with inventorying the ENTIRE department’s chemicals, and to put chemicals back where they belonged if we found any that were mismatched.

One day we were going through the research labs, and we came across a hood that had a SHIT TON of chemicals in it. Instead of trying to find out where they all went, we named a folder in the inventory system “Hood 32″ (it was in Hood 32….). Annie goes “that’d be a GREAT name for a short story.” I ended up naming my blog after it during that job (because it sounds cool, right? ;) )

I ended up working for the professor whose hood had all those chemicals in it, which was an awesome coincidence.

THEN when I went to Montana to work, I worked in Hood 32 AGAIN.

So it stuck :)

Stupid Lab Mistakes: a Constant Across All Levels of Experience

So today was day one of a tyrosinase lab. We had to centrifuge our organic matter sample (homogenized mushroom gills) to separate the soluble proteins from the rest of the tissue, and we counterbalanced our sample with an identical centrifuge tube of equal weight filled with water. We did all of this under the supervision of a TA and our professor.

My lab partners and I have used centrifuges many times before, but what we (and the instructors) failed to notice was that these particular tubes required an adapter for this particular centrifuge. We were spinning it up to about 7000 rcf when we heard a muffled “bang,” then the centrifuge slowed to a stop. When we opened it up, we discovered that the water tube had EXPLODED, shattering into a hundred little plastic pieces. the tube containing our organic sample slurry was thankfully intact, but it was badly warped and cracked. We spent the next 20 minutes or so carefully wiping water off every nook and cranny of the centrifuge interior, thanking our lucky stars that it wasn’t mushroom gloop.

I keep thinking that gaining more practical lab experience will save me from this kind of thing, but if the three different generations of chemists present couldn’t keep it from happening then there is no hope. These incidents are the things that add unexpected excitement to my life, though, so I suppose it’s not all bad.

This beautifully diverse group of sea slugs can be found in oceans worldwide, but its greatest variety is located in the magical habitat of warm, shallow reefs. It’s name comes from the Latin for “naked” (nudus), but it’s often informally called a “sea slug.” Today, a profile of a group of marine gastropods called Nudibranchia.

Unlike other mollusks (think snails), most nudibranchs have lost their shells, evolving other mechanisms for protection. For example, some are able to ingest and retain poisons found in prey, later secreting them for defense.

All known nudibranchs are carnivorous, feeding on a variety of sea life including sponges, other sea slugs, and barnacles. One species, Glaucus atlanticus, is known to prey on the Portuguese man o’ war!

Hermaphroditic, nudibranchs have a set of reproductive organs for both sexes, which means any creature can mate with another. That said, a nudibranch can’t fertilize itself.

According to National Geographic, “some nudibranchs are solar-powered, storing algae in their outer tissues and living off the sugars produced by the algae’s photosynthesis.”

The creature has very simple eyes (able to distinguish little more beyond light and dark), but have cephalic (head) tentacles that are sensitive to touch, taste, and smell. Its gills are uncovered, located behind their heart, and protrude in plumes on their back, making for a large surface area that grants more efficient oxygen exchange.

(Image Credits: Creative Commons, clockwise, richard ling, Raymond, Peter Liu Photography / Source: National Geographic, Wikimedia Commons, Earth Touch, Murky Secrets: The Marine Creatures of the Lembeh Strait)

-

echo1331 reblogged this · 8 years ago

echo1331 reblogged this · 8 years ago -

lonestrr-blog liked this · 8 years ago

lonestrr-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

yerpmerp3-blog liked this · 8 years ago

yerpmerp3-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

nidokinng reblogged this · 8 years ago

nidokinng reblogged this · 8 years ago -

mrblackdeath-blog liked this · 8 years ago

mrblackdeath-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

secretagentpeptidebond reblogged this · 8 years ago

secretagentpeptidebond reblogged this · 8 years ago -

dansdansdans3-blog liked this · 8 years ago

dansdansdans3-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

occasionalsideboob reblogged this · 8 years ago

occasionalsideboob reblogged this · 8 years ago -

occasionalsideboob liked this · 8 years ago

occasionalsideboob liked this · 8 years ago -

zerostatereflex liked this · 8 years ago

zerostatereflex liked this · 8 years ago -

tojiswhore-aventurinesslut reblogged this · 8 years ago

tojiswhore-aventurinesslut reblogged this · 8 years ago -

coolfayebunny liked this · 8 years ago

coolfayebunny liked this · 8 years ago -

bbafer-franklin liked this · 8 years ago

bbafer-franklin liked this · 8 years ago -

aeternumquaerere reblogged this · 8 years ago

aeternumquaerere reblogged this · 8 years ago -

aeternumquaerere liked this · 8 years ago

aeternumquaerere liked this · 8 years ago -

knitflick reblogged this · 8 years ago

knitflick reblogged this · 8 years ago -

knitflick liked this · 8 years ago

knitflick liked this · 8 years ago -

yesimalittlestenographess reblogged this · 8 years ago

yesimalittlestenographess reblogged this · 8 years ago -

echo1331 liked this · 8 years ago

echo1331 liked this · 8 years ago -

prince-oscar-moved reblogged this · 8 years ago

prince-oscar-moved reblogged this · 8 years ago -

sciencesourceimages reblogged this · 8 years ago

sciencesourceimages reblogged this · 8 years ago