What Scariest Word A Nuclear Physicist Can Say?

What scariest word a nuclear physicist can say?

Oops.

More Posts from Science-is-magical and Others

ALL ROLLED UP

A newly identified mineral christened merelaniite tightly rolls up like a scroll as it crystallizes, forming shiny dark gray needles up to a few millimeters in length (Minerals 2016, DOI: 10.3390/min6040115). The overall formula of the mineral is Mo₄Pb₄VSbS₁₅. It crystallizes into a sheet composed primarily of alternating ultrathin layers of MoS₂ and PbS. “It’s like a natural nanocomposite,” says research team leader John A. Jaszczak of Michigan Technological University. Strain from the interacting layers likely causes the crystalline sheets to wrap around themselves as they grow. Jaszczak and coworkers named the mineral for the Merelani mining district in Tanzania, where the merelaniite samples originated. Collaborating research institutions included the U.K. Natural History Museum, U.S. National Museum of Natural History, and University of Florence.

Credit: Minerals (both)

Related C&EN content:

Minerals in Medicine Exhibition

Worldwide Hunt For Missing Carbon Minerals Begins

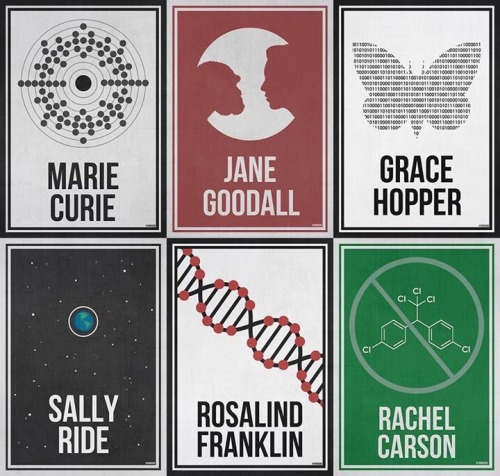

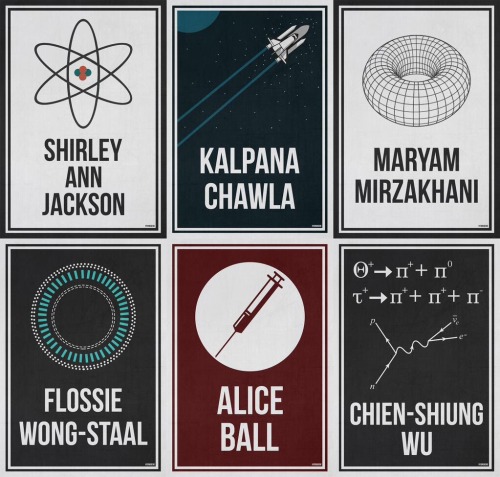

The complete ‘Women Who Changed Science - And The World" collection in honor of the 95th Women’s Equality Day.

Purchase Here!

Missed any of the graphics featured in C&EN? They’ve now put a page together so you can find all of the graphics in one place, on subjects including Guinness, daffodils, barbecue & more: ow.ly/RB10e

How playing an instrument benefits your brain

Recent research about the mental benefits of playing music has many applications, such as music therapy for people with emotional problems, or helping to treat the symptoms of stroke survivors and Alzheimer’s patients. But it is perhaps even more significant in how much it advances our understanding of mental function, revealing the inner rhythms and complex interplay that make up the amazing orchestra of our brain.

Did you know that every time musicians pick up their instruments, there are fireworks going off all over their brain? On the outside they may look calm and focused, reading the music and making the precise and practiced movements required. But inside their brains, there’s a party going on.

From the TED-Ed lesson How playing an instrument benefits your brain - Anita Collins

Animation by Sharon Colman Graham

How Printing a 3-D Skull Helped Save a Real One

What started as a stuffy-nose and mild cold symptoms for 15-year-old Parker Turchan led to a far more serious diagnosis: a rare type of tumor in his nose and sinuses that extended through his skull near his brain.

“He had always been a healthy kid, so we never imagined he had a tumor,” says Parker’s father, Karl. “We didn’t even know you could get a tumor in the back of your nose.”

The Portage, Michigan, high school sophomore was referred to the University of Michigan’s C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital, where doctors determined the tumor extended so deep that it was beyond what regular endoscopy could see.

The team members needed to get the best representation of the tumor’s extent to ensure that their surgical approach could successfully remove the entire mass

“Parker had an uncommon, large, high-stage tumor in a very challenging area,” says Mott pediatric head and neck surgeon David Zopf, M.D. “The tumor’s location and size had me question whether a minimally invasive approach would allow us to remove the tumor completely.”

To help answer that question, teams at Mott sought an innovative approach: crafting a 3-D replica of Parker’s skull.

The model, made of polylactic acid, helped simulate the coming operation on Parker by giving U-M surgeons “an exact replica of his craniofacial anatomy and a way to essentially touch the ‘tumor’ with our hands ahead of time,” Zopf says.

Just as important, it also allowed the team to counsel Parker and his family by offering them a look at what lurked within — and, with the test run successfully complete, what would lie ahead.

A ‘pretty impressive’ model

The rare and aggressive tumor in Parker’s nose is known as juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma, a mass that grows in the back of the nasal cavity and predominantly affects young male teens. Mott sees a handful of cases each year.

In Parker’s case, the tumor had two large parts: one roughly the size of an egg and the other the size of a kiwi. The mass sat right in the center of the craniofacial skeleton below the brain and next to the nerves that control eye movement and vision.

“We were obviously concerned about the risks involved in this kind of procedure, which we knew could lead to a lot of blood loss and was sensitive because it was so close to the nerves in his face,” says Karl, who praised the 3-D methodology used to aid his son. “It was pretty impressive to see the model of Parker’s skull ahead of the surgery. We had no idea this was even possible.”

Zopf, working with Erin McKean, M.D., a U-M skull base surgeon, was able to completely remove the large tumor. Kyle VanKoevering, M.D., and Sajad Arabnejad, Ph.D., aided in model preparation.

Through preoperative embolization, the blood supply to the tumor was blocked off the day before surgery to decrease blood loss. A large portion of the tumor was then detached endoscopically and removed through the mouth. The remaining mass under the brain was taken out through the nose.

Doctors took pictures of Parker’s anatomy during the surgery and, later, compared it with pictures from the model. They were nearly identical.

“Words alone can’t express how thankful we are for Parker’s talented team of surgeons at Mott,” says his mother, Heidi. “Parker is back to his old self again.”

Powerful potential

Although medical application of the technology continues to gain attention, it isn’t entirely new. Zopf and Mott teams have used 3-D printing for almost five years.

Groundbreaking 3-D printed splints made at U-M have helped save the lives of babies with severe tracheobronchomalacia, which causes the windpipe to periodically collapse and prevents normal breathing. Mott has also used 3-D printing on a fetus to plan for a potentially complicated birth.

“We are finding more and more uses for 3-D printing in medicine,” Zopf says. “It is proving to be a powerful tool that will allow for enhanced patient care.”

Based on success in patients such as Parker and continued collaboration, it’s a concept that appears poised to thrive.

“Because of the team approach we’ve established at the University of Michigan between otolaryngology and biomedical engineering, the printed models can be designed and rapidly produced at a very low cost,” Zopf says. “Michigan is one of only a few places in the nation and world that has the capacity to do this.”

-

lojy900320 liked this · 6 years ago

lojy900320 liked this · 6 years ago -

science-is-magical reblogged this · 8 years ago

science-is-magical reblogged this · 8 years ago -

vaping-paradise liked this · 8 years ago

vaping-paradise liked this · 8 years ago -

ravioliwings liked this · 8 years ago

ravioliwings liked this · 8 years ago -

alychampignon reblogged this · 8 years ago

alychampignon reblogged this · 8 years ago -

greenlarryfairy liked this · 9 years ago

greenlarryfairy liked this · 9 years ago -

outatheaftermath reblogged this · 9 years ago

outatheaftermath reblogged this · 9 years ago -

now-nacho liked this · 9 years ago

now-nacho liked this · 9 years ago -

nyausgris liked this · 9 years ago

nyausgris liked this · 9 years ago -

pyroinohio liked this · 9 years ago

pyroinohio liked this · 9 years ago -

willworkforadam liked this · 9 years ago

willworkforadam liked this · 9 years ago -

pixelpirate7 reblogged this · 9 years ago

pixelpirate7 reblogged this · 9 years ago -

offbynone reblogged this · 9 years ago

offbynone reblogged this · 9 years ago -

wittyandprettyfatbabe reblogged this · 9 years ago

wittyandprettyfatbabe reblogged this · 9 years ago -

mars-euphoria liked this · 9 years ago

mars-euphoria liked this · 9 years ago -

ignus7 reblogged this · 9 years ago

ignus7 reblogged this · 9 years ago -

megane-the-bard reblogged this · 9 years ago

megane-the-bard reblogged this · 9 years ago -

keialuma reblogged this · 9 years ago

keialuma reblogged this · 9 years ago -

imbricator liked this · 9 years ago

imbricator liked this · 9 years ago -

youre-you-i-am-me reblogged this · 9 years ago

youre-you-i-am-me reblogged this · 9 years ago -

darling-im-just-a-painter reblogged this · 9 years ago

darling-im-just-a-painter reblogged this · 9 years ago -

darling-im-just-a-painter liked this · 9 years ago

darling-im-just-a-painter liked this · 9 years ago -

praisethedarkness reblogged this · 9 years ago

praisethedarkness reblogged this · 9 years ago -

demoniclove1-blog liked this · 9 years ago

demoniclove1-blog liked this · 9 years ago -

thisismeok liked this · 9 years ago

thisismeok liked this · 9 years ago -

messythoughtsinthenight liked this · 9 years ago

messythoughtsinthenight liked this · 9 years ago -

devils-advocates-blog1 liked this · 9 years ago

devils-advocates-blog1 liked this · 9 years ago -

a-slip-on-the-keyboard reblogged this · 9 years ago

a-slip-on-the-keyboard reblogged this · 9 years ago -

bee--tree reblogged this · 9 years ago

bee--tree reblogged this · 9 years ago -

sippingmychai reblogged this · 9 years ago

sippingmychai reblogged this · 9 years ago -

modest-magnemite reblogged this · 9 years ago

modest-magnemite reblogged this · 9 years ago -

modest-magnemite liked this · 9 years ago

modest-magnemite liked this · 9 years ago -

saumonfume liked this · 9 years ago

saumonfume liked this · 9 years ago -

insaltandburn reblogged this · 9 years ago

insaltandburn reblogged this · 9 years ago -

insaltandburn liked this · 9 years ago

insaltandburn liked this · 9 years ago -

secretlyawallflower reblogged this · 9 years ago

secretlyawallflower reblogged this · 9 years ago -

catkillingcannibal reblogged this · 9 years ago

catkillingcannibal reblogged this · 9 years ago -

artsyallouette liked this · 9 years ago

artsyallouette liked this · 9 years ago