The Origin Of Species By Means Of Natural Selection Or The Preservation Of Favoured Races In The Struggle

The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the struggle for life Charles Darwin

London John Murray Sixth Edition with additions and corrections (Forty Third Thousand) The sixth edition [shown here] (first printed in 1872) - is the edition in which the word “evolution” was used for the first time (although Darwin used this term in the Descent of Man, published a year before; in 1871). This edition was also the last that Charles Darwin revised during his lifetime, including the addition of an entirely new chapter. In 1876 Darwin added a few small corrections, and all subsequent printing were copies of that printing.

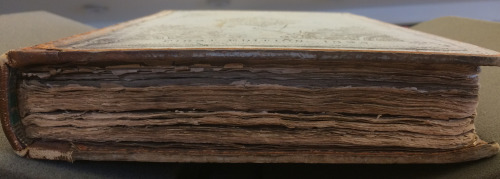

a clean tight fresh presentable copy - which remains largely unread - even after 124 years - a large portion of the book remains unopened [the leaves of the book remain joined at the folds; not slit apart]

More Posts from Philosophical-amoeba and Others

I read once that shortly before The Merchant Of Venice was written, Queen Elizabeths doctor (who was Jewish) tried to poison her; is that true?

Sort of.

There was a doctor accused of trying to poison Queen Elizabeth. His name was Roderigo Lopez. He was Jewish and of Spanish descent and was fairly well off. He was accused of trying to poison her and conspiring against her with Spanish officials. I believe he is the only English physician to have been executed.

HOWEVER, we don’t know if he actually wanted to poison her. There was no attempt I believe, just accusations. He stated before he died that he “loved the Queen as much as he loved Jesus Christ” which can (and was) be interpreted in many ways. Some people think the Queen thought he was innocent because she took a long time to sign his death warrant. The character may have been the inspiration for Shylock in the Merchant of Venice, since they are both considered villains and evil because they’re Jewish but no one is 100% sure. Based on what I’ve heard, I don’t think he actually wanted to poison the queen and was probably just a target of antisemitism and maybe anti Spanish sentiment but who knows.

Thanks for bringing this up! I’m sure people would love to read about it. I’ve put the Wikipedia article below:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roderigo_Lopez#Royal_physician

-Admin @thesunofyork

Chai Tea

Word for tea in most of the world’s languages are all ultimately related, belonging to two groups of terms.

“Tea” itself belongs to one of those groups. It was a borrowing from Dutch thee, in turn from tê, the reading of 茶 in the Amoy dialect of Min Nan. Those languages whose introduction to tea was primaraly from Dutch traders typically use words likewise derived via the Dutch thee. The Polish herbata is also part of this family, though slightly obscured, being a borrowing from the Latin herba thea.

The other major group is represented by the word chai, a more recent borrowing in English. Chai was borrowed from the Hindi cāy, which in turn came from a Chinese dialect with a form similar to Mandarin chá. Languages that use chai-type terms generally were first introduced to tea through overland trade, ultimately to northern China, while those that use tea-type terms were generally introduced to it via sea trade, from Southern China.

Both tê and chá are derived from the same Middle Chinese form, ultimately derived from Proto-Sino-Tibetan *s-la “leaf”.

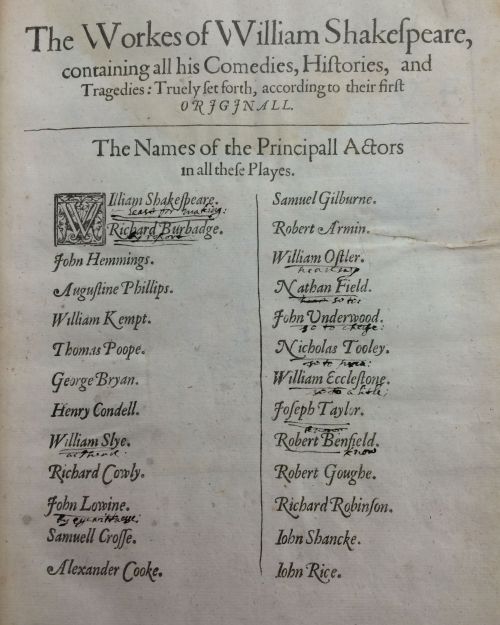

Happy almost birthday, Shakespeare! Or should I say Bard-thday? Recently, in honour of the 400th anniversary of William Shakespeare’s death (conveniently for celebratory purposes, he was born on April 23 1564 and died on the same day in 1616), I was given the incredible opportunity to have a private audience to go through the University of Glasgow’s copy of the First Folio, page by page. I’ve written a short article for the University Library’s blog, which you can find here, but I wanted to share some other images on my own blog that I didn’t have room for on the official post!

The University of Glasgow’s First Folio (more properly known as Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies) is able to tell so many more stories than those of the plays contained in its pages- of the history of the antiquarian book trade, of the printing practices of the Renaissance, of book ownership and value. Rest assured, you’ll probably be seeing posts from me in the future about all of these things, as well as the typographical ornaments used in the book, which I found fascinating. The University’s Folio is particularly interesting due to the notations by past owners, including one who had apparently seen at least one of the original Chamberlain’s Men “By eyewittnesse”. But my favourite bit of the later additions is the morbid little poem on the reverse of one of the flyleaves: “Pitty it is the fam’d Shakespeare/ Shall ever want his chin or haire.”

List of medieval European scientists

Anthemius of Tralles (ca. 474 – ca. 534): a professor of geometry and architecture, authored many influential works on mathematics and was one of the architects of the famed Hagia Sophia, the largest building in the world at its time. His works were among the most important source texts in the Arab world and Western Europe for centuries after.

John Philoponus (ca. 490–ca. 570): also known as John the Grammarian, a Christian Byzantine philosopher, launched a revolution in the understanding of physics by critiquing and correcting the earlier works of Aristotle. In the process he proposed important concepts such as a rudimentary notion of inertia and the invariant acceleration of falling objects. Although his works were repressed at various times in the Byzantine Empire, because of religious controversy, they would nevertheless become important to the understanding of physics throughout Europe and the Arab world.

Paul of Aegina (ca. 625–ca. 690): considered by some to be the greatest Christian Byzantine surgeon, developed many novel surgical techniques and authored the medical encyclopedia Medical Compendium in Seven Books. The book on surgery in particular was the definitive treatise in Europe and the Islamic world for hundreds of years.

The Venerable Bede (ca. 672–735): a Christian monk of the monasteries of Wearmouth and Jarrow who wrote a work On the Nature of Things, several books on the mathematical / astronomical subject of computus, the most influential entitled On the Reckoning of Time. He made original discoveries concerning the nature of the tides and his works on computus became required elements of the training of clergy, and thus greatly influenced early medieval knowledge of the natural world.

Rabanus Maurus (c. 780 – 856): a Christian monk and teacher, later archbishop of Mainz, who wrote a treatise on Computus and the encyclopedic work De universo. His teaching earned him the accolade of "Praeceptor Germaniae," or "the teacher of Germany."

Abbas Ibn Firnas (810 – 887): a polymath and inventor in Muslim Spain, made contributions in a variety of fields and is most known for his contributions to glass-making and aviation. He developed novel ways of manufacturing and using glass. He broke his back at an unsuccessful attempt at flying a primitive hang glider in 875.

Pope Sylvester II (c. 946–1003): a Christian scholar, teacher, mathematician, and later pope, reintroduced the abacus and armillary sphere to Western Europe after they had been lost for centuries following the Greco-Roman era. He was also responsible in part for the spread of the Hindu-Arabic numeral system in Western Europe.

Maslamah al-Majriti (died 1008): a mathematician, astronomer, and chemist in Muslim Spain, made contributions in many areas, from new techniques for surveying to updating and improving the astronomical tables of al-Khwarizmi and inventing a process for producing mercury oxide.[citation needed] He is most famous, though, for having helped transmit knowledge of mathematics and astronomy to Muslim Spain and Christian Western Europe.

Abulcasis (936-1013): a physician and scientist in Muslim Spain, is considered to be the father of modern surgery. He wrote numerous medical texts, developed many innovative surgical instruments, and developed a variety of new surgical techniques and practices. His texts were considered the definitive works on surgery in Europe until the Renaissance.

Constantine the African (c. 1020&–1087): a Christian native of Carthage, is best known for his translating of ancient Greek and Roman medical texts from Arabic into Latin while working at the Schola Medica Salernitana in Salerno, Italy. Among the works he translated were those of Hippocrates and Galen.

Arzachel (1028–1087): the foremost astronomer of the early second millennium, lived in Muslim Spain and greatly expanded the understanding and accuracy of planetary models and terrestrial measurements used for navigation. He developed key technologies including the equatorium and universal latitude-independent astrolabe.

Avempace (died 1138): a famous physicist from Muslim Spain who had an important influence on later physicists such as Galileo. He was the first to theorize the concept of a reaction force for every force exerted.

Adelard of Bath (c. 1080 – c. 1152): was a 12th-century English scholar, known for his work in astronomy, astrology, philosophy and mathematics.

Avenzoar (1091–1161): from Muslim Spain, introduced an experimental method in surgery, employing animal testing in order to experiment with surgical procedures before applying them to human patients.[4] He also performed the earliest dissections and postmortem autopsies on both humans as well as animals.

Robert Grosseteste (1168–1253): Bishop of Lincoln, was the central character of the English intellectual movement in the first half of the 13th century and is considered the founder of scientific thought in Oxford. He had a great interest in the natural world and wrote texts on the mathematical sciences of optics, astronomy and geometry. In his commentaries on Aristotle's scientific works, he affirmed that experiments should be used in order to verify a theory, testing its consequences. Roger Bacon was influenced by his work on optics and astronomy.

Albert the Great (1193–1280): Doctor Universalis, was one of the most prominent representatives of the philosophical tradition emerging from the Dominican Order. He is one of the thirty-three Saints of the Roman Catholic Church honored with the title of Doctor of the Church. He became famous for his vast knowledge and for his defence of the pacific coexistence between science and religion. Albert was an essential figure in introducing Greek and Islamic science into the medieval universities, although not without hesitation with regard to particular Aristotelian theses. In one of his most famous sayings he asserted: "Science does not consist in ratifying what others say, but of searching for the causes of phenomena." Thomas Aquinas was his most famous pupil.

John of Sacrobosco (c. 1195 – c. 1256): was a scholar, monk, and astronomer (probably English, but possibly Irish or Scottish) who taught at the University of Paris and wrote an authoritative and influential mediaeval astronomy text, the Tractatus de Sphaera; the Algorismus, which introduced calculations with Hindu-Arabic numerals into the European university curriculum; the Compotus ecclesiasticis on Easter reckoning; and the Tractatus de quadrante on the construction and use of the astronomical quadrant.

Jordanus de Nemore (late 12th, early 13th century): was one of the major pure mathematicians of the Middle Ages. He wrote treatises on mechanics ("the science of weights"), on basic and advanced arithmetic, on algebra, on geometry, and on the mathematics of stereographic projection.

Villard de Honnecourt (fl. 13th century): a French engineer and architect who made sketches of mechanical devices such as automatons and perhaps drew a picture of an early escapement mechanism for clockworks.

Roger Bacon (1214–94): Doctor Admirabilis, joined the Franciscan Order around 1240 where, influenced by Grosseteste, Alhacen and others, he dedicated himself to studies where he implemented the observation of nature and experimentation as the foundation of natural knowledge. Bacon wrote in such areas as mechanics, astronomy, geography and, most of all, optics. The optical research of Grosseteste and Bacon established optics as an area of study at the medieval university and formed the basis for a continuous tradition of research into optics that went all the way up to the beginning of the 17th century and the foundation of modern optics by Kepler.[8]

Ibn al-Baitar (died 1248): a botanist and pharmacist in Muslim Spain, researched over 1400 types of plants, foods, and drugs and compiled pharmaceutical and medical encyclopedias documenting his research. These were used in the Islamic world and Europe until the 19th century.

Theodoric Borgognoni (1205-1296): was an Italian Dominican friar and Bishop of Cervia who promoted the uses of both antiseptics and anaesthetics in surgery. His written work had a deep impact on Henri de Mondeville, who studied under him while living in Italy and later became the court physician for King Philip IV of France.

William of Saliceto (1210-1277): was an Italian surgeon of Lombardy who advanced medical knowledge and even challenged the work of the renowned Greco-Roman surgeon Galen (129-216 AD) by arguing that allowing pus to form in wounds was detrimental to the health of he patient.

Thomas Aquinas (1227–74): Doctor Angelicus, was an Italian theologian and friar in the Dominican Order. As his mentor Albert the Great, he is a Catholic Saint and Doctor of the Church. In addition to his extensive commentaries on Aristotle's scientific treatises, he was also said to have written an important alchemical treatise titled Aurora Consurgens. However, his most lasting contribution to the scientific development of the period was his role in the incorporation of Aristotelianism into the Scholastic tradition.

Arnaldus de Villa Nova (1235-1313): was an alchemist, astrologer, and physician from the Crown of Aragon who translated various Arabic medical texts, including those of Avicenna, and performed optical experiments with camera obscura.

John Duns Scotus (1266–1308): Doctor Subtilis, was a member of the Franciscan Order, philosopher and theologian. Emerging from the academic environment of the University of Oxford. where the presence of Grosseteste and Bacon was still palpable, he had a different view on the relationship between reason and faith as that of Thomas Aquinas. For Duns Scotus, the truths of faith could not be comprehended through the use of reason. Philosophy, hence, should not be a servant to theology, but act independently. He was the mentor of one of the greatest names of philosophy in the Middle Ages: William of Ockham.

Mondino de Liuzzi (c. 1270-1326): was an Italian physician, surgeon, and anatomist from Bologna who was one of the first in Medieval Europe to advocate for the public dissection of cadavers for advancing the field of anatomy. This followed a long-held Christian ban on dissections performed by the Alexandrian school in the late Roman Empire.

William of Ockham (1285–1350): Doctor Invincibilis, was an English Franciscan friar, philosopher, logician and theologian. Ockham defended the principle of parsimony, which could already be seen in the works of his mentor Duns Scotus. His principle later became known as Occam's Razor and states that if there are various equally valid explanations for a fact, then the simplest one should be chosen. This became a foundation of what would come to be known as the scientific method and one of the pillars of reductionism in science. Ockham probably died of the Black Plague. Jean Buridan and Nicole Oresme were his followers.

Jacopo Dondi dell'Orologio (1290-1359): was an Italian doctor, clockmaker, and astronomer from Padua who wrote on a number of scientific subjects such as pharmacology, surgery, astrology, and natural sciences. He also designed an astronomical clock.

Richard of Wallingford (1292-1336): an English abbot, mathematician, astronomer, and horologist who designed an astronomical clock as well as an equatorium to calculate the lunar, solar and planetary longitudes, as well as predict eclipses.

Jean Buridan (1300–58): was a French philosopher and priest. Although he was one of the most famous and influent philosophers of the late Middle Ages, his work today is not renowned by people other than philosophers and historians. One of his most significant contributions to science was the development of the theory of impetus, that explained the movement of projectiles and objects in free-fall. This theory gave way to the dynamics of Galileo Galilei and for Isaac Newton's famous principle of Inertia.

Guy de Chauliac (1300-1368): was a French physician and surgeon who wrote the Chirurgia magna, a widely read publication throughout medieval Europe that became one of the standard textbooks for medical knowledge for the next three centuries. During the Black Death he clearly distinguished Bubonic Plague and Pneumonic Plague as separate diseases, that they were contagious from person to person, and offered advice such as quarantine to avoid their spread in the population. He also served as the personal physician for three successive popes of the Avignon Papacy.

John Arderne (1307-1392): was an English physician and surgeon who invented his own anesthetic that combined hemlock, henbane, and opium. In his writings, he also described how to properly excise and remove the abscess caused by anal fistula.

Nicole Oresme (c. 1323–82): was one of the most original thinkers of the 14th century. A theologian and bishop of Lisieux, he wrote influential treatises in both Latin and French on mathematics, physics, astronomy, and economics. In addition to these contributions, Oresme strongly opposed astrology and speculated about the possibility of a plurality of worlds.

Giovanni Dondi dell'Orologio (c. 1330-1388): was a clockmaker from Padua, Italy who designed the astarium, an astronomical clock and planetarium that utilized the escapement mechanism that had been recently invented in Europe. He also attempted to describe the mechanics of the solar system with mathematical precision.

Barefoot to school… Clogher, Co Tyrone, Ireland, from the Rose Shaw collection

The hairstyle of this small girl, cut short and topped with a ribbon bow, seems to date this advertisement from the early 1950s. The printer is believed to be Whitcombe & Tombs, because the poster came to the Library with other material printed by that company.

[Whitcombe & Tombs Ltd?] :Goodness! that’s tempting. Weet-bix [ca 1954?]

Eph-C-FOOD-Whitcombe-2-03

The Fibonacci sequence can help you quickly convert between miles and kilometers

The Fibonacci sequence is a series of numbers where every new number is the sum of the two previous ones in the series.

1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, etc. The next number would be 13 + 21 = 34.

Here’s the thing: 5 mi = 8 km. 8 mi = 13 km. 13 mi = 21 km, and so on.

Edit: You can also do this with multiples of these numbers (e.g. 5*10 = 8*10, 50 mi = 80 km). If you’ve got an odd number that doesn’t fit in the sequence, you can also just round to the nearest Fibonacci number and compensate for this in the answer. E.g. 70 mi ≈ 80 mi. 80 mi = 130 km. Subtract a small value like 15 km to compensate for the rounding, and the end result is 115 km.

This works because the Fibonacci sequence increases following the golden ratio (1:1.618). The ratio between miles and km is 1:1.609, or very, very close to the golden ratio. Hence, the Fibonacci sequence provides very good approximations when converting between km and miles.

-

cryptidwilliam liked this · 3 years ago

cryptidwilliam liked this · 3 years ago -

just-some-guy-42 liked this · 3 years ago

just-some-guy-42 liked this · 3 years ago -

wisephilosopherpolice liked this · 3 years ago

wisephilosopherpolice liked this · 3 years ago -

b0und2u-blog liked this · 3 years ago

b0und2u-blog liked this · 3 years ago -

crazystarlitsky liked this · 3 years ago

crazystarlitsky liked this · 3 years ago -

the-wine-dark-sea liked this · 3 years ago

the-wine-dark-sea liked this · 3 years ago -

jumont-wonderer liked this · 3 years ago

jumont-wonderer liked this · 3 years ago -

reinventinghamish liked this · 3 years ago

reinventinghamish liked this · 3 years ago -

all-too-human-storiesxd reblogged this · 3 years ago

all-too-human-storiesxd reblogged this · 3 years ago -

elenamalia liked this · 3 years ago

elenamalia liked this · 3 years ago -

brickx reblogged this · 3 years ago

brickx reblogged this · 3 years ago -

brickx reblogged this · 3 years ago

brickx reblogged this · 3 years ago -

brickx liked this · 3 years ago

brickx liked this · 3 years ago -

looniecartooni liked this · 3 years ago

looniecartooni liked this · 3 years ago -

marilyndclack liked this · 3 years ago

marilyndclack liked this · 3 years ago -

withoutfurthereloquence liked this · 3 years ago

withoutfurthereloquence liked this · 3 years ago -

queen-of-carven-stone liked this · 3 years ago

queen-of-carven-stone liked this · 3 years ago -

gloamingx reblogged this · 3 years ago

gloamingx reblogged this · 3 years ago -

thedarklordhasreturnedtonarnia liked this · 3 years ago

thedarklordhasreturnedtonarnia liked this · 3 years ago -

daydreamodyssey liked this · 3 years ago

daydreamodyssey liked this · 3 years ago -

dennisthemenacetosociety liked this · 3 years ago

dennisthemenacetosociety liked this · 3 years ago -

wired-weirdness liked this · 3 years ago

wired-weirdness liked this · 3 years ago -

ksandrayoung1994 liked this · 3 years ago

ksandrayoung1994 liked this · 3 years ago -

longshankstumblarian reblogged this · 3 years ago

longshankstumblarian reblogged this · 3 years ago -

rethinkagain liked this · 3 years ago

rethinkagain liked this · 3 years ago -

celestialily liked this · 3 years ago

celestialily liked this · 3 years ago -

texteschoisis liked this · 3 years ago

texteschoisis liked this · 3 years ago -

earthrevolvesaroundben reblogged this · 3 years ago

earthrevolvesaroundben reblogged this · 3 years ago -

earthrevolvesaroundben liked this · 3 years ago

earthrevolvesaroundben liked this · 3 years ago -

maiamaia liked this · 3 years ago

maiamaia liked this · 3 years ago -

i-live-in-a-bucket reblogged this · 3 years ago

i-live-in-a-bucket reblogged this · 3 years ago -

stevenoggsworld reblogged this · 3 years ago

stevenoggsworld reblogged this · 3 years ago -

stevenoggsworld liked this · 3 years ago

stevenoggsworld liked this · 3 years ago -

mistressredbottoms liked this · 3 years ago

mistressredbottoms liked this · 3 years ago -

marxist-junglism liked this · 3 years ago

marxist-junglism liked this · 3 years ago

A reblog of nerdy and quirky stuff that pique my interest.

291 posts