Tough As A Tardigrade

Tough as a Tardigrade

Without water, a human can only survive for about 100 hours. But there’s a creature so resilient that it can go without it for decades. This one millimeter animal can survive both the hottest and coldest environments on Earth, and can even withstand high levels of radiation. This is the tardigrade, and it’s one of the toughest creatures on Earth, even if it does look more like a chubby, eight-legged gummy bear.

Most organisms need water to survive. Water allows metabolism to occur, which is the process that drives all the biochemical reactions that take place in cells. But creatures like the tardigrade, also known as the water bear, get around this restriction with a process called anhydrobiosis, from the Greek meaning life without water. And however extraordinary, tardigrades aren’t alone. Bacteria, single-celled organisms called archaea, plants, and even other animals can all survive drying up.

For many tardigrades, this requires that they go through something called a tun state. They curl up into a ball, pulling their head and eight legs inside their body and wait until water returns. It’s thought that as water becomes scarce and tardigrades enter their tun state, they start synthesize special molecules, which fill the tardigrade’s cells to replace lost water by forming a matrix.

Components of the cells that are sensitive to dryness, like DNA, proteins, and membranes, get trapped in this matrix. It’s thought that this keeps these molecules locked in position to stop them from unfolding, breaking apart, or fusing together. Once the organism is rehydrated, the matrix dissolves, leaving behind undamaged, functional cells.

Beyond dryness, tardigrades can also tolerate other extreme stresses: being frozen, heated up past the boiling point of water, high levels of radiation, and even the vacuum of outer space. This has led to some erroneous speculation that tardigrades are extraterrestrial beings.

While that’s fun to think about, scientific evidence places their origin firmly on Earth where they’ve evolved over time. In fact, this earthly evolution has given rise to over 1100 known species of tardigrades and there are probably many others yet to be discovered. And because tardigrades are so hardy, they exist just about everywhere. They live on every continent, including Antarctica. And they’re in diverse biomes including deserts, ice sheets, the sea fresh water, rainforests, and the highest mountain peaks. But you can find tardigrades in the most ordinary places, too, like moss or lichen found in yards, parks, and forests. All you need to find them is a little patience and a microscope.

Scientists are now to trying to find out whether tardigrades use the tun state, their anti-drying technique, to survive other stresses. If we can understand how they, and other creatures, stabilize their sensitive biological molecules, perhaps we could apply this knowledge to help us stabilize vaccines, or to develop stress-tolerant crops that can cope with Earth’s changing climate.

And by studying how tardigrades survive prolonged exposure to the vacuum of outer space, scientists can generate clues about the environmental limits of life and how to safeguard astronauts. In the process, tardigrades could even help us answer a critical question: could life survive on planets much less hospitable than our own?

From the TED-Ed Lesson Meet the tardigrade, the toughest animal on Earth - Thomas Boothby

Animation by Boniato Studio

More Posts from Philosophical-amoeba and Others

“Brainprint” Biometric ID Hits 100% Accuracy

Psychologists and engineers at Binghamton University in New York say they’ve hit a milestone in the quest to use the unassailable inner workings of the mind as a form of biometric identification. They came up with an electroencephalograph system that proved 100 percent accurate at identifying individuals by the way their brains responded to a series of images. But EEG as a practical means of authentication is still far off.

Many earlier attempts had come close to 100 percent accuracy but couldn’t completely close the gap. “It’s a big deal going from 97 to 100 percent because we imagine the applications for this technology being for high-security situations,” says Sarah Laszlo, the assistant professor of psychology at Binghamton who led the research with electrical engineering professor Zhanpeng Jin.

Perhaps as important as perfect accuracy is that this new form of ID can do something fingerprints and retinal scans have a hard time achieving: It can be “canceled.”

Fingerprint authentication can be reset if the associated data is stolen, because that data can be stored as a mathematically transformed version of itself, points out Clarkson University biometrics expert Stephanie Schuckers. However, that trick doesn’t work if it’s the fingerprint (or the finger) itself that’s stolen. And the theft part, at least, is easier than ever. In 2014 hackers claimed to have cloned German defense minister Ursula von der Leyen’s fingerprints just by taking a high-definition photo of her hands at a public event.

Several early attempts at EEG-based identification sought the equivalent of a fingerprint in the electrical activity of a brain at rest. But this new brain biometric, which its inventors call CEREBRE, dodges the cancelability problem because it’s based on the brain’s responses to a sequence of particular types of images. To keep that ID from being permanently hijacked, those images can be changed or re-sorted to essentially make a new biometric passkey, should the original one somehow be hacked.

CEREBRE, which Laszlo, Jin, and colleagues described in IEEE Transactions in Information Forensics and Security, involves presenting a person wearing an EEG system with images that fall into several categories: foods people feel strongly about, celebrities who also evoke emotions, simple sine waves of different frequencies, and uncommon words. The words and images are usually black and white, but occasionally one is presented in color because that produces its own kind of response.

Each image causes a recognizable change in voltage at the scalp called an event-related potential, or ERP. The different categories of images involve somewhat different combinations of parts of your brain, and they were already known to produce slight differences in the shapes of ERPs in different people. Laszlo’s hypothesis was that using all of them—several more than any other system—would create enough different ERPs to accurately distinguish one person from another.

The EEG responses were fed to software called a classifier. After testing several schemes, including a variety of neural networks and other machine-learning tricks, the engineers found that what actually worked best was a system based on simple cross correlation.

In the experiments, each of the 50 test subjects saw a sequence of 500 images, each flashed for 1 second. “We collected 500, knowing it was overkill,” Laszlo says. Once the researchers crunched the data they found that just 27 images would have been enough to hit the 100 percent mark.

The experiments were done with a high-quality research-grade EEG, which used 30 electrodes attached to the skull with conductive goop. However, the data showed that the system needs only three electrodes for 100 percent identification, and Laszlo says her group is working on simplifying the setup. They’re testing consumer EEG gear from Emotiv and NeuroSky, and they’ve even tried to replicate the work with electrodes embedded in a Google Glass, though the results weren’t spectacular, she says.

For EEG to really be taken seriously as a biometric ID, brain interfaces will need to be pretty commonplace, says Schuckers. That might yet happen. “As we go more and more into wearables as a standard part of our lives, [EEGs] might be more suitable,” she says.

But like any security system, even an EEG biometric will attract hackers. How can you hack something that depends on your thought patterns? One way, explains Laszlo, is to train a hacker’s brain to mimic the right responses. That would involve flashing light into a hacker’s eye at precise times while the person is observing the images. These flashes are known to alter the shape of the ERP.

Breakthrough on ash dieback

UK scientists have identified the country’s first ash tree that shows tolerance to ash dieback.

Ash dieback is spreading throughout the UK and in one woodland in Norfolk, a great number of trees are infected.

The team compared the genetics of trees with different levels of tolerance to ash dieback disease. From there, they developed three genetic markers which enabled them to predict whether or not a tree is likely to be tolerant to the disease. One tree named Betty, they discovered, was predicted to show strong tolerance.

The findings raise the possibility of using selective breeding to develop strains of trees that are tolerant to the disease to help safeguard our forests.

Read more

Images: Close-up infected ash petioles (leaf stems) - Copyright: John Innes Centre

George Michael was 23 when he sat for this interview, which has never been broadcast before.

He had just embarked on his solo career after leaving Wham!. During the conversation, George Michael talks about his sexuality and shedding his pop-ballad persona ala Careless Whisper. He reflects on the power of his fame, as he recalls the historical trip Wham! took to play in communist-China in 1985.

NEW from @blankonblank!

BHL Book Feature: The Birds of Singapore Island

Our book feature this week is The Birds of Singapore Island (1927), co-authored by John Alexander Strachey Bucknill and Frederick Nutter Chase with SciArt by Gerald Aylmer Levett-Yeats, and published by the Raffles Museum. This work is the first book on the birds of Singapore!

Our featured illustration is a Greater Racket-tailed Drongo (Dicrurus paradiseus platurus). This book is written in an informal, non-scientific style to appeal to tourists and bird enthusiasts, and the description of the Greater Racket-tailed Drongo is a good example of this writing style.

All this week, we will be sharing several of the 31 plates from The Birds of Singapore Island, which was digitized for BHL by National Library Board, Singapore. You can view all of the plates from this work in our Flickr album, and check out our blog post, which was written by Ong Eng Chuan, Senior Librarian of the National Library Board, Singapore.

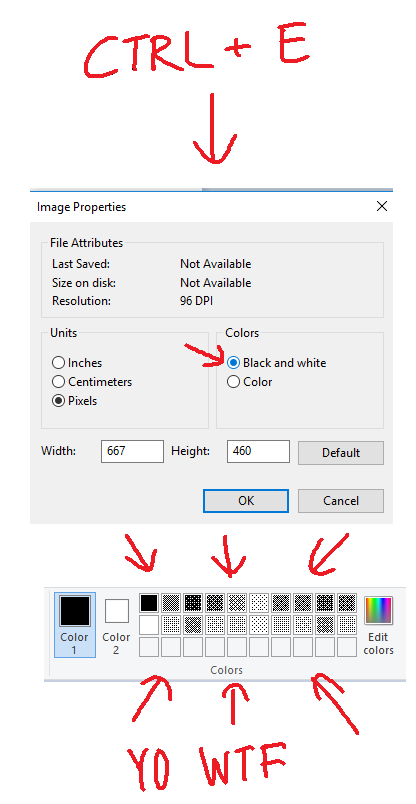

Do you any tips about using ms paint?

I think I have few tips

#1Use 500x500 px or bigger canvas size. Any smaller size will make a brush look messy and shit.Here look:

Can you see the difference?? Lineart in 600x600 px is so much smoother

#2

#3

#4 RIGHT MOUSE BUTTON YOU NEED IT

#5

*:・゚✧it’s like manga : *✧・゚

that’s all tbh

i hope this was somewhat helpful

The Icelandic Language still uses the letters Þ and Ð, which used to be in the English alphabet too but which fell into disuse and were eventually left out altogether. Their pronunciation is the sound made by the “th” in “this” and “that” respectively.

Incidentally, the Þ was not included in early English printing press types. As a substitute they used y, which looks somewhat similar. Thus was the popular misconception born that English people used to say “ye” as in “ye old shoppe.”

Dolphins beat up octopuses before eating them, and the reason is kind of horrifying

Generally speaking, it’s best if your food doesn’t kill you. This isn’t usually a problem in the animal kingdom, as prey tends to be dead and limp by the time it hits the gullet. But not all creatures are harmless after death: consider the octopus.

Read more

Artist profile: Gerard Sekoto

‘Art is the spark, the illumination which is socially significant for it brings about understanding’ – Gerard Sekoto (1913–1993)

Gerard Sekoto was born in Botshabelo, Mpumalanga province, in 1913, the year in which the Natives Land Act dispossessed many black South Africans of their ancestral lands. In 1938 Sekoto moved to Sophiatown, Johannesburg. He held his first solo exhibition the following year, and in 1940 the Johannesburg Art Gallery purchased his work Yellow Houses – A Street in Sophiatown (1939–1940). It was the first painting by a black South African artist to be acquired by a South African art institution, although Sekoto had to pose as a cleaner to see his own painting hanging in the gallery.

Sekoto based this painting, titled Song of the Pick (1946), on a photograph taken in the 1930s of black South African workers labouring under the watchful eye of a white foreman standing behind them. However, in his painting the dynamic has changed. Sekoto has enhanced the grace and power of the labourers, turning them to confront the small and puny figure of the overseer, who appears about to be impaled by their pickaxes.

Sekoto painted this work in the township of Eastwood in Pretoria, shortly before moving to Paris in what became a lifelong exile from South Africa. During the 1980s, postcard-sized reproductions of this iconic painting were widely distributed in South Africa, as both a badge of honour and a source of inspiration in the struggle against apartheid.

Explore a diverse range of art stretching back 100,000 years in our exhibition South Africa: the art of a nation (27 October 2016 – 26 February 2017).

Exhibition sponsored by Betsy and Jack Ryan

Logistics partner IAG Cargo

Song of the Pick, 1946. Image © Iziko Museums of South Africa, Art Collections, Cape Town. Photo by Carina Beyer.

Song of the Pick was based on this image, taken by photographer Andrew Goldie in the 1930s.

-

deanstryker reblogged this · 1 year ago

deanstryker reblogged this · 1 year ago -

deanstryker liked this · 1 year ago

deanstryker liked this · 1 year ago -

taolucidity reblogged this · 1 year ago

taolucidity reblogged this · 1 year ago -

glamboyl reblogged this · 1 year ago

glamboyl reblogged this · 1 year ago -

quaileqq reblogged this · 1 year ago

quaileqq reblogged this · 1 year ago -

vinipaiva liked this · 1 year ago

vinipaiva liked this · 1 year ago -

madawnla reblogged this · 2 years ago

madawnla reblogged this · 2 years ago -

distracteddaintydemon liked this · 2 years ago

distracteddaintydemon liked this · 2 years ago -

pebbs06 liked this · 2 years ago

pebbs06 liked this · 2 years ago -

taolucidity reblogged this · 3 years ago

taolucidity reblogged this · 3 years ago -

glamboyl reblogged this · 3 years ago

glamboyl reblogged this · 3 years ago -

spaceofmischief reblogged this · 3 years ago

spaceofmischief reblogged this · 3 years ago -

shauntaydaniels liked this · 3 years ago

shauntaydaniels liked this · 3 years ago -

shauntaydaniels reblogged this · 3 years ago

shauntaydaniels reblogged this · 3 years ago -

bunchan529 liked this · 3 years ago

bunchan529 liked this · 3 years ago -

madtechnomage reblogged this · 3 years ago

madtechnomage reblogged this · 3 years ago -

madtechnomage liked this · 3 years ago

madtechnomage liked this · 3 years ago -

gritsinmisery reblogged this · 3 years ago

gritsinmisery reblogged this · 3 years ago -

the-littlest-peanut liked this · 3 years ago

the-littlest-peanut liked this · 3 years ago -

where-it-flows reblogged this · 3 years ago

where-it-flows reblogged this · 3 years ago -

where-it-flows liked this · 3 years ago

where-it-flows liked this · 3 years ago -

rockcandyshrike liked this · 3 years ago

rockcandyshrike liked this · 3 years ago -

kitsune-sam reblogged this · 3 years ago

kitsune-sam reblogged this · 3 years ago -

whatdoyoumeanyoureatsoup reblogged this · 3 years ago

whatdoyoumeanyoureatsoup reblogged this · 3 years ago -

metaldragonqueen reblogged this · 3 years ago

metaldragonqueen reblogged this · 3 years ago -

gritsinmisery liked this · 3 years ago

gritsinmisery liked this · 3 years ago -

dolklen liked this · 3 years ago

dolklen liked this · 3 years ago -

fractalindigo reblogged this · 3 years ago

fractalindigo reblogged this · 3 years ago -

kiwiiwantsacookie liked this · 3 years ago

kiwiiwantsacookie liked this · 3 years ago

A reblog of nerdy and quirky stuff that pique my interest.

291 posts