Paralyzed ALS Patient Operates Speech Computer With Her Mind

Paralyzed ALS patient operates speech computer with her mind

In the UMC Utrecht a brain implant has been placed in a patient enabling her to operate a speech computer with her mind. The researchers and the patient worked intensively to get the settings right. She can now communicate at home with her family and caregivers via the implant. That a patient can use this technique at home is unique in the world. This research was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Because she suffers from ALS disease, the patient is no longer able to move and speak. Doctors placed electrodes in her brain, and the electrodes pick up brain activity. This enables her to wirelessly control a speech computer that she now uses at home.

Mouse click

The patient operates the speech computer by moving her fingers in her mind. This changes the brain signal under the electrodes. That change is converted into a mouse click. On a screen in front of her she can see the alphabet, plus some additional functions such as deleting a letter or word and selecting words based on the letters she has already spelled. The letters on the screen light up one by one. She selects a letter by influencing the mouse click at the right moment with her brain. That way she can compose words, letter by letter, which are then spoken by the speech computer. This technique is comparable to actuating a speech computer via a push-button (with a muscle that can still function, for example, in the neck or hand). So now, if a patient lacks muscle activity, a brain signal can be used instead.

Wireless

The patient underwent surgery during which electrodes were placed on her brain through tiny holes in her skull. A small transmitter was then placed in her body below her collarbone. This transmitter receives the signals from the electrodes via subcutaneous wires, amplifies them and transmits them wirelessly. The mouse click is calculated from these signals, actuating the speech computer. The patient is closely supervised. Shortly after the operation, she started on a journey of discovery together with the researchers to find the right settings for the device and the perfect way to get her brain activity under control. It started with a “simple” game to practice the art of clicking. Once she mastered clicking, she focused on the speech computer. She can now use the speech computer without the help of the research team.

The UMC Utrecht Brain Center has spent many years researching the possibility of controlling a computer by means of electrodes that capture brain activity. Working with a speech computer driven by brain signals measured with a bathing cap with electrodes has long been tested in various research laboratories. That a patient can use the technique at home, through invisible, implanted electrodes, is unique in the world.

If the implant proves to work well in three people, the researchers hope to launch a larger, international trial. Ramsey: “We hope that these results will stimulate research into more advanced implants, so that some day not only people with communication problems, but also people with paraplegia, for example, can be helped.”

More Posts from Philosophical-amoeba and Others

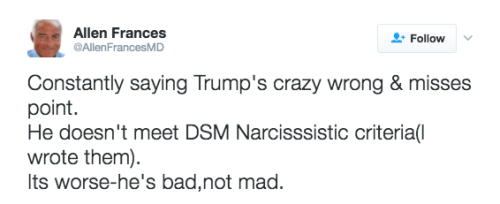

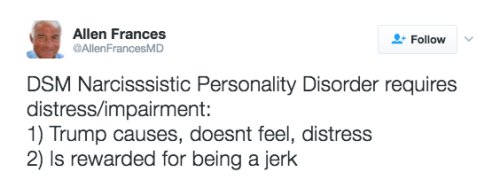

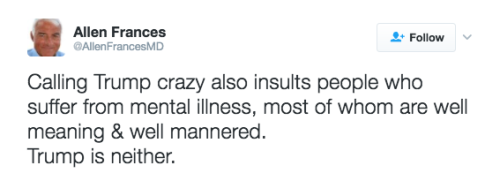

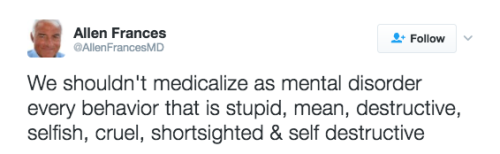

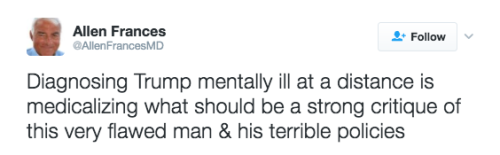

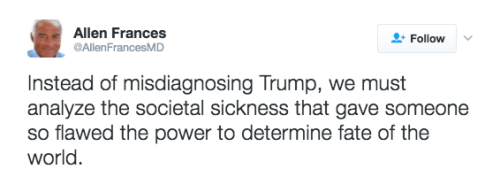

The psychiatrist who wrote the criteria for narcissism just made an extremely important point about what’s wrong with diagnosing Trump with mental disorders

Dr. Allen Frances says in speculating about Trump’s mental health, we are doing a disservice to those who do suffer from mental illness. In a series of tweets, he explained why he doesn’t think Trump is a narcissist — and how harmful it can be for us to keep assuming that he is.

Antibiotic resistance is one of the most pressing problems of our times. Traditional antimicrobial drugs aren’t working the way they used to, and the rise of “superbugs” could bring about the post-antibiotic age, where easily treatable infections suddenly become life-threatening incurable illnesses.

There have been a slew of new discoveries recently that have revealed brand new ways to turn the tide, but the latest revelation at the hands of a team from George Mason University is a particularly unusual sounding one. As it turns out, we could use the blood of dragons to annihilate superbugs.

No, this isn’t an analogy or a plot line from Game of Thrones. The devil-toothed Komodo dragon – the devious beast from Indonesia – has a particular suite of chemical compounds in its blood that’s pure anathema to a wide range of bacteria.

They’re known as CAMPs – cationic antimicrobial peptides – and although plenty of living creatures (including humans) have versions of these, Komodo dragons have 48, with 47 of them being powerfully antimicrobial. The team managed to cleverly isolate these CAMPs in a laboratory by using electrically-charged hydrogels – strange, aerated substances – to suck them out of the dragons’ blood samples.

Synthesizing their own versions of eight of these CAMPs, they put them up against two strains of lab-grown “superbugs,” MRSA and Pseudomona aeruginosa, to see if they had any effect. Remarkably, all eight were able to kill the latter, whereas seven of them destroyed all trace of both, doing something that plenty of conventional antibiotic drugs couldn’t.

Writing in the Journal of Proteome Research, the researchers write that these powerful CAMPs explain why Komodo dragons are able to contain such a dense, biodiverse population of incredibly dangerous bacteria in their mouths. Although it’s not clear where all these bacteria originally came from, the chemical compounds in their blood ensures that they’ll never be properly infected.

In fact, it was this ability to co-exist with such lethal bacteria that piqued the interest of the researchers in the first place.

“Komodo dragon serum has been demonstrated to have in vitro antibacterial properties,” they note. “The role that CAMPs play in the innate immunity of the Komodo dragon is potentially very informative, and the newly identified Komodo dragon CAMPs may lend themselves to the development of new antimicrobial therapeutics.”

It’ll be awhile before these CAMPs are tested in human trials, but the idea that we’re effectively using dragon’s blood, or plasma, to fight against resurgent diseases is genuinely quite thrilling. Alongside Hulk-like drugs that physically rip bacteria apart, there’s a chance that, with the help of these legendary lizards, we may win this war yet.

David in Singapore, Serious Moonlight Tour 1983

Photo © Denis O’Regan

Computer Science/Engineering Masterpost

Online lectures:

Discrete Mathematics (x) (x) (x) (x) (x)

Data Structures (x) (x) (x) (x) (and Object Oriented Programming (x) )

Software Engineering (x)

Database (x)

Operating Systems (x) (x) (x) (x) (x) (x) (x)

Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs (x)

Computer Architecture (x)

Programming (x) (x) (x) (x) (x) (x) (x)

Linear Algebra (x) (x) (x)

Artificial Intelligence (x) (x)

Algorithms (x)

Calculus (x) (x) (x)

Tutorials (programming) and other online resources:

Programming languages online tutorials and Computer Science/Engineering online courses

Java tutorial

Java, C, C++ tutorials

Memory Management in C

Pointers in C/C++

Algorithms

Genetic Algorithms

Websites for learning and tools:

Stack Overflow

Khan Academy

Mathway

Recommended books:

Computer organization and design: the hardware/software interface. David A.Patterson & John L. Hennessy.

Artificial intelligence: a modern approac. Stuart J. Russel & Peter Norvig.

Database systems: the complete book. Hector Garcia-Molina, Jeffrey D. Ullman, Jennifer Widom.

Algorithms: a functional programming approach. Fethi Rabbi & Guy Lapalme.

Data Structures & Algorithms in Java: Michael T. Goodrich & Roberto Tamassia.

The C programming language: Kernighan, D. & Ritchie.

Operating System Concepts: Avi Silberschatz, Peter Baer Galvin, Greg Gagne.

Study Tips:

How to Study

Exam Tips for Computer Science

Top 10 Tips For Computer Science Students

Study Skills: Ace Your Computing Science Courses

How to study for Computer Science exams

How to be a successful Computer Science student

Writing in Sciences, Mathematics and Engineering:

Writing a Technical Report

Writing in the Sciences (Stanford online course)

Writing in Mathematics, Statistics and Computer Science Courses

What’s Up for May 2016?

What’s Up for May? Two huge solar system highlights: Mercury transits the sun and Mars is closer to Earth than it has been in 11 years.

On May 9, wake up early on the west coast or step out for coffee on the east coast to see our smallest planet cross the face of the sun. The transit will also be visible from most of South America, western Africa and western Europe.

A transit occurs when one astronomical body appears to move across the face of another as seen from Earth or from a spacecraft. But be safe! You’ll need to view the sun and Mercury through a solar filter when looking through a telescope or when projecting the image of the solar disk onto a safe surface. Look a little south of the sun’s Equator. It will take about 7 ½ hours for the tiny planet’s disk to cross the sun completely. Since Mercury is so tiny it will appear as a very small round speck, whether it’s seen through a telescope or projected through a solar filter. The next Mercury transit will be Nov. 11, 2019.

Two other May highlights involve Mars. On May 22 Mars opposition occurs. That’s when Mars, Earth and the sun all line up, with Earth directly in the middle.

Eight days later on May 30, Mars and Earth are nearest to each other in their orbits around the sun. Mars is over half a million miles closer to Earth at closest approach than at opposition. But you won’t see much change in the diameter and brightness between these two dates. As Mars comes closer to Earth in its orbit, it appears larger and larger and brighter and brighter.

During this time Mars rises after the sun sets. The best time to see Mars at its brightest is when it is highest in the sky, around midnight in May and a little earlier in June.

Through a telescope you can make out some of the dark features on the planet, some of the lighter features and sometimes polar ice and dust storm-obscured areas showing very little detail.

After close approach, Earth sweeps past Mars quickly. So the planet appears large and bright for only a couple weeks.

But don’t worry if you miss 2016’s close approach. 2018’s will be even better, as Mars’ close approach will be, well, even closer.

You can find out about our #JourneytoMars missions at mars.nasa.gov, and you can learn about all of our missions at http://www.nasa.gov.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

These travel booklets from throughout the UK were collected by Barbara Denison over the course of three decades, part of a larger collection consisting of dozens of volumes. Text-dense and diagram-heavy guides like these were meant to both give guidance while visiting and act as inexpensive momentos afterwards. Most of the booklets in the collection concern cathedrals, abbeys, and ruined castles that Denison visited over the course of her travels.

im putting together a couple of scottish folk mixes bc that’s what i do and im honestly curious if anyone in my country has ever been unequivocally happy about anything ever

Ojiya chijimi summer kimono, seen on

This type of kimono is made in Niigata prefecture (old Echigo province). Hemp kimono fabric bolt (tanmono) are laid outside to be whitened by sunlight reflecting on the snow. This process is similar to the one used for yuki-tsumugi kimono, and both are registrered as UNESCO Immaterial Heritage.

This process is depicted in Kawabata’s Yukiguni (Snow country)

The chijimi creased effect is considered very chic. Snow-made fabrics are especially appreciated for summer clothings.

The code that took America's Apollo 11 to the moon in the 1960's has been published

When programmers at the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory set out to develop the flight software for the Apollo 11 space program in the mid-1960s, the necessary technology did not exist. They had to invent it.

They came up with a new way to store computer programs, called “rope memory,” and created a special version of the assembly programming language. Assembly itself is obscure to many of today’s programmers—it’s very difficult to read, intended to be easily understood by computers, not humans. For the Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC), MIT programmers wrote thousands of lines of that esoteric code.

Here’s a very 1960s data visualization of just how much code they wrote—this is Margaret Hamilton, director of software engineering for the project, standing next to a stack of paper containing the software:

The AGC code has been available to the public for quite a while–it was first uploaded by tech researcher Ron Burkey in 2003, after he’d transcribed it from scanned images of the original hardcopies MIT had put online. That is, he manually typed out each line, one by one.

“It was scanned by an airplane pilot named Gary Neff in Colorado,” Burkey said in an email. “MIT got hold of the scans and put them online in the form of page images, which unfortunately had been mutilated in the process to the point of being unreadable in places.” Burkey reconstructed the unreadable parts, he said, using his engineering skills to fill in the blanks.

“Quite a bit later, I managed to get some replacement scans from Gary Neff for the unreadable parts and fortunately found out that the parts I filled in were 100% correct!” he said.

As enormous and successful as Burkey’s project has been, however, the code itself remained somewhat obscure to many of today’s software developers. That was until last Thursday (July 7), when former NASA intern Chris Garry uploaded the software in its entirety to GitHub, the code-sharing site where millions of programmers hang out these days.

Within hours, coders began dissecting the software, particularly looking at the code comments the AGC’s original programmers had written. In programming, comments are plain-English descriptions of what task is being performed at a given point. But as the always-sharp joke detectives in Reddit’s r/ProgrammerHumor section found, many of the comments in the AGC code go beyond boring explanations of the software itself. They’re full of light-hearted jokes and messages, and very 1960s references.

One of the source code files, for example, is called BURN_BABY_BURN--MASTER_IGNITION_ROUTINE, and the opening comments explain why:

About 900 lines into that subroutine, a reader can see the playfulness of the original programming team come through, in the first and last comments in this block of code:

In the file called LUNAR_LANDING_GUIDANCE_EQUATIONS.s, it appears that two lines of code were meant to be temporary ended up being permanent, against the hopes of one programmer:

In the same file, there’s also code that appears to instruct an astronaut to “crank the silly thing around.”

“That code is all about positioning the antenna for the LR (landing radar),” Burkey explained. “I presume that it’s displaying a code to warn the astronaut to reposition it.”

And in the PINBALL_GAME_BUTTONS_AND_LIGHTS.s file, which is described as “the keyboard and display system program … exchanged between the AGC and the computer operator,” there’s a peculiar Shakespeare quote:

This is likely a reference to the AGC programming language itself, as one Reddit user . The language used predetermined “nouns” and “verbs” to execute operations. The verb pointed out 37, for example, means “Run program,” while the noun 33 means “Time to ignition.”

Now that the code is on GitHub, programmers can actually suggest changes and file issues. And, of course, they have

What the heck is ‘Johnston’s Fluid Beef’? According to this Victorian age flyer in the Canada Medical and Surgical Journal of April 1883, it is “the most perfect food for invalids ever introduced, concentrated preparation for nutritious beef tea or soup, specially recommended by the Medical Faculty.” But the directions for use on page 4 may be a recipe for botulism: “Add a small teaspoon to a cup of boiling water and season to taste; or as a sandwich paste it may be used on toast, with or without butter. The can may remain open for weeks without detriment to the contents.”

The story of ‘Johnston’s Fluid Beef’ began in 1870 in the Franco-Prussian War, when Napoleon III ordered a million cans of beef to feed troops. John Lawson Johnston, a Scot living in Montreal, had the task of providing it. Transportation and storage were problematic, so Johnston created a product known as Johnston’s Fluid Beef, later called Bovril, to meet the need. By 1888, Johnston’s Fluid Beef became a British staple sold in 3,000 U.K. public houses, grocers and dispensing chemists, and remains so today. A major downturn in sales occurred in 2004 when the company changed its formula to make Bovril vegetarian. The Guardian reported in 2007: “Rather than any new-found vegetarian gusto, the move [by Bovril] to yeast extract in 2004 was largely triggered by concerns about beef consumption and BSE [bovine spongiform encephalopathy], which affected Bovril’s export market.” But by 2006, the beef was back in Bovril and the company survives. Modern directions for use are recommended.

-

moonknightzone626 liked this · 7 years ago

moonknightzone626 liked this · 7 years ago -

fairytalesandimaginings liked this · 8 years ago

fairytalesandimaginings liked this · 8 years ago -

philosophical-amoeba reblogged this · 8 years ago

philosophical-amoeba reblogged this · 8 years ago -

hearteyesroseskies liked this · 8 years ago

hearteyesroseskies liked this · 8 years ago -

potatosupporter liked this · 8 years ago

potatosupporter liked this · 8 years ago -

akzel liked this · 8 years ago

akzel liked this · 8 years ago -

idlewordsmith reblogged this · 8 years ago

idlewordsmith reblogged this · 8 years ago -

idlewordsmith liked this · 8 years ago

idlewordsmith liked this · 8 years ago -

buruuhan reblogged this · 8 years ago

buruuhan reblogged this · 8 years ago -

buruuhan liked this · 8 years ago

buruuhan liked this · 8 years ago -

medblrgirl reblogged this · 8 years ago

medblrgirl reblogged this · 8 years ago -

medblrgirl liked this · 8 years ago

medblrgirl liked this · 8 years ago -

medistatic reblogged this · 8 years ago

medistatic reblogged this · 8 years ago -

intrainingdoc reblogged this · 8 years ago

intrainingdoc reblogged this · 8 years ago -

anigabu-blog reblogged this · 8 years ago

anigabu-blog reblogged this · 8 years ago -

tomodellswife-blog liked this · 8 years ago

tomodellswife-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

anamerch reblogged this · 8 years ago

anamerch reblogged this · 8 years ago -

imaginina liked this · 8 years ago

imaginina liked this · 8 years ago -

elsvoid-blog reblogged this · 8 years ago

elsvoid-blog reblogged this · 8 years ago -

elkorel reblogged this · 8 years ago

elkorel reblogged this · 8 years ago -

elkorel liked this · 8 years ago

elkorel liked this · 8 years ago -

bukwyvrm liked this · 8 years ago

bukwyvrm liked this · 8 years ago -

writerthatwritesthings-blog reblogged this · 8 years ago

writerthatwritesthings-blog reblogged this · 8 years ago -

writerthatwritesthings-blog liked this · 8 years ago

writerthatwritesthings-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

daloko liked this · 8 years ago

daloko liked this · 8 years ago -

mysterymercedes-blog1 liked this · 8 years ago

mysterymercedes-blog1 liked this · 8 years ago -

thavinceman reblogged this · 8 years ago

thavinceman reblogged this · 8 years ago -

thavinceman liked this · 8 years ago

thavinceman liked this · 8 years ago -

tumblerhasfun liked this · 8 years ago

tumblerhasfun liked this · 8 years ago -

deercake24 liked this · 8 years ago

deercake24 liked this · 8 years ago -

somesadassnews reblogged this · 8 years ago

somesadassnews reblogged this · 8 years ago -

solitaryfossil liked this · 8 years ago

solitaryfossil liked this · 8 years ago -

opakakaek reblogged this · 8 years ago

opakakaek reblogged this · 8 years ago -

edueliasam liked this · 8 years ago

edueliasam liked this · 8 years ago -

killerfranky reblogged this · 8 years ago

killerfranky reblogged this · 8 years ago -

lazilyherphilosopher liked this · 8 years ago

lazilyherphilosopher liked this · 8 years ago -

things-i-read reblogged this · 8 years ago

things-i-read reblogged this · 8 years ago

A reblog of nerdy and quirky stuff that pique my interest.

291 posts