What Happens In The Brain During Unconsciousness?

What Happens in the Brain During Unconsciousness?

Researchers are shining a light on the darkness of the unconscious brain. Three new studies add to the body of knowledge.

When patients undergo major surgery, they’re often put under anesthesia to allow the brain to be in an unconscious state.

But what’s happening in the brain during that time?

Three Michigan Medicine researchers are authors on three new articles from the Center for Consciousness Science exploring this question — specifically how brain networks fragment in association with a variety of unconsciousness states.

“These studies come from a long-standing hypothesis my colleagues and I have had regarding the essential characteristic of why we are conscious and how we become unconscious, based on patterns of information transfer in the brain,” says George A. Mashour, M.D., Ph.D., professor of anesthesiology, director of the Center for Consciousness Science and associate dean for clinical and translational research at the University of Michigan Medical School.

In the studies, the team not only explores how the brain networks fragment, but also how better to measure what is happening.

“We’ve been working for a decade to understand in a more refined way how the spatial and temporal aspects of brain function break down during unconsciousness, how we can measure that breakdown and the implications for information processing,” says UnCheol Lee, Ph.D., physicist, assistant professor of anesthesiology and associate director of the Center for Consciousness Science.

Examining different aspects of unconsciousness

The basis for the three studies, as well as other work from the Center for Consciousness Science, comes from a theory Mashour produced during his residency.

“I published a theoretical article when I was a resident in anesthesiology suggesting that anesthesia doesn’t work by turning the brain off, per se, but rather by isolating processes in certain areas of the brain,” Mashour says. “Instead of seeing a highly connected brain network, anesthesia results in an array of islands with isolated cognition and processing. We have taken this thought, as well as the work of others, and built upon it with our research.”

In the study in the Journal of Neuroscience, the team analyzed different areas of the brain during sedation, surgical anesthesia and a vegetative state.

“It’s often suggested that different areas of the brain that typically talk to one another get out of sync during unconsciousness,” says Anthony Hudetz, Ph.D., professor of anesthesiology, scientific director of the Center for Consciousness Science and senior author on the study. “We showed in the early stages of sedation, the information processing timeline gets much longer and local areas of the brain become more tightly connected within themselves. That tightening might lead to the inability to connect with distant areas.”

In the Frontiers in Human Neuroscience study, the team delved into how the brain integrates information and how it can be measured in the real world.

“We took a very complex computational task of measuring information integration in the brain and broke it down into a more manageable task,” says Lee, senior author on the study. “We demonstrated that as the brain gets more modular and has more local conversations, the measure of information integration starts to decrease. Essentially, we looked at how the brain network fragmentation was taking place and how to measure that fragmentation, which gives us the sense of why we lose consciousness.”

Finally, the latest article, in Trends in Neurosciences, aimed to take the team’s previous studies and other work on the subject of unconsciousness and put together a fuller picture.

“We examined unconsciousness across three different conditions: physiological, pharmacological and pathological,” says Mashour, lead author on the study. “We found that during unconsciousness, disrupted connectivity in the brain and greater modularity are creating an environment that is inhospitable to the kind of efficient information transfer that is required for consciousness.”

How these studies can help patients

The team members at the Center for Consciousness Science note that all of this work may help patients in the future.

“We’re looking for a better way to quantify the depth of anesthesia in the operating room and to assess consciousness in someone who has had a stroke or brain damage,” Hudetz says. “For example, we may assume that a patient is fully unconscious based on behavior, but in some cases consciousness can persist despite unresponsiveness.”

The team hopes this and future research could lead to therapeutic strategies for patients.

“We want to understand the communication breakdown that occurs in the brain during unconsciousness so we can precisely target or monitor these circuits to achieve safer anesthesia and restore these circuits to improve outcomes of coma,” Mashour says.

More Posts from Contradictiontonature and Others

It’s nearly the season of the witch: time for some cauldron chemistry

Midwives and nurses sometimes came under suspicion because of their specialised knowledge and success - or failure - in treating those who were sick. These healing roles were traditionally taken on by women who, until around the turn of the nineteenth century, were excluded from formal medical training. However, many still practiced medicine in their homes and villages, and what they had learned came from shared knowledge and trial and error, rather than accepted official sources. A medical education might not have been a great help in any case. In the days before germ theory the causes of sickness and the reasons for recovery were not obvious. Any recoveries could be seen as miraculous … or the result of witchcraft.

Treating sickness and disease pre-germ theory was largely guesswork. All sorts of noxious compounds were administered to ailing individuals, and if they produced any effect on the body, be it vomiting, diarrhoea or sweating, it was seen as a good thing – and that was the practice of the so-called professionals. It is not hard to see how images of unofficial healers and herbalists (both men and women) stooping over boiling pots of herbs, roots and who-knows-what, could become a template for the image of a witch, especially when many of the concoctions they produced had such unpleasant effects on their patients.

Having said that, herbalists and traditional healers should not be dismissed as completely ignorant of the medical benefits of some of the plants and poultices they used. Some of the ingredients associated with traditional healing and witches’ potions have been found to be hugely beneficial to medicine once they have been isolated, tested and modified. Science has enabled us to identify the key components of some plants and test them to determine how and when they should be administered safely and effectively. Chemists have modified the structures of some of the compounds to reduce side-effects, make drugs more potent or lower their toxicity.

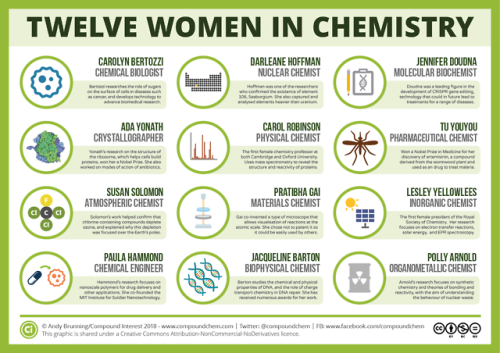

For International Women’s Day, here are 12 women from chemistry history: wp.me/p4aPLT-2ra and 12 from chemistry present: wp.me/p4aPLT-5w7

WHAT??? Time to update those textbooks.

Did life begin on land rather than in the sea?

Stromatolites are round, multilayered mineral structures that range from the size of golf balls to weather balloons and represent the oldest evidence that there were living organisms on Earth 3.5 billion years ago.

Scientists who believed life began in the ocean thought these mineral formations had formed in shallow, salty seawater, just like living stromatolites in the World Heritage-listed area of Shark Bay, which is a two-day drive from the Pilbara.

But what Djokic discovered amid the strangling heat and blood-red rocks of the region was evidence that the stromatolites had not formed in salt water but instead in conditions more like the hot springs of Yellowstone.

The discovery pushed back the time for the emergence of microbial life on land by 580 million years and also bolstered a paradigm-shifting hypothesis laid out by UC Santa Cruz astrobiologists David Deamer and Bruce Damer: that life began, not in the sea, but on land.

Stromatolites.Credit: © Ints / Fotolia

If you dropped a water balloon on a bed of nails, you’d expect it to burst spectacularly. And you’d be right – some of the time. Under the right conditions, though, you’d see what a high-speed camera caught in the animation above: a pancake-shaped bounce with nary a leak. Physically, this is a scaled-up version of what happens to a water droplet when it hits a superhydrophobic surface.

Water repellent superhydrophobic surfaces are covered in microscale roughness, much like a bed of tiny nails. When the balloon (or droplet) hits, it deforms into the gaps between posts. In the case of the water balloon, its rubbery exterior pulls back against that deformation. (For the droplet, the same effect is provided by surface tension.) That tension pulls the deformed parts of the balloon back up, causing the whole balloon to rebound off the nails in a pancake-like shape. For more, check out this video on the student balloon project or the original water droplet research. (Image credits: T. Hecksher et al., Y. Liu et al.; via The New York Times; submitted by Justin B.)

At last, we’ve seen what might be the primary building blocks of memories lighting up in the brains of mice.

We have cells in our brains – and so do rodents – that keep track of our location and the distances we’ve travelled. These neurons are also known to fire in sequence when a rat is resting, as if the animal is mentally retracing its path – a process that probably helps memories form, says Rosa Cossart at the Institut de Neurobiologie de la Méditerranée in Marseille, France.

But without a way of mapping the activity of a large number of these individual neurons, the pattern that these replaying neurons form in the brain has been unclear. Researchers have suspected for decades that the cells might fire together in small groups, but nobody could really look at them, says Cossart.

To get a look, Cossart and her team added a fluorescent protein to the neurons of four mice. This protein fluoresces the most when calcium ions flood into a cell – a sign that a neuron is actively firing. The team used this fluorescence to map neuron activity much more widely than previous techniques, using implanted electrodes, have been able to do.

Observing the activity of more than 1000 neurons per mouse, the team watched what happened when mice walked on a treadmill or stood still.

As expected, when the mice were running, the neurons that trace how far the animal has travelled fired in a sequential pattern, keeping track.

These same cells also lit up while the mice were resting, but in a strange pattern. As they reflected on their memories, the neurons fired in the same sequence as they had when the animals were running, but much faster. And rather than firing in turn individually, they fired together in sequential blocks that corresponded to particular fragments of a mouse’s run.

“We’ve been able to image the individual building-blocks of memory,” Cossart says, each one reflecting a chunk of the original episode that the mouse experienced.

Continue Reading.

NASA unveils greatest views of the aurorae ever, from space in HD

“When the free electrons finally find the ions they bind to, they drop down in energy, creating an incredible display of colorful possibilities. Of all of them, it’s the oxygen (mostly, with the strong emission line at 558 nanometers) and the nitrogen (secondary, with the smaller line at a slightly higher wavelength) that create the familiar, spectacular green color we most commonly associate with aurorae, but blues and reds — often at higher altitudes — are sometimes possible, too, with contributions from all three of the major atmospheric elements and their combinations.”

The northern (aurora borealis) and southern (aurora australis) lights are caused by a combination of three phenomena on our world, that make our aurorae unique among all worlds in our solar system:

Outbursts from the Sun that can go in any direction,

Our magnetic field, that funnels charged particles into circles around the poles,

And our atmospheric composition, that causes the colors and the displays we see.

Put all of these together and add in a 4k camera aboard the ISS, and you’ve got an outstanding recipe for the greatest aurora video ever composed. Here’s the in-depth science behind it, too.

Hepatitis B in a Laboratory!! #serology #infection #liver #hepatitis #medicine #medstudent #medstudynotes #virus #medschool #microbiology #pathology https://www.instagram.com/p/BrIYa-LheyH/?utm_source=ig_tumblr_share&igshid=lqm0j92yobw0

We Just Moved One Step Closer to Understanding (and Defeating) Alzheimer’s

(Image caption: Brandeis University professor Ricardo Godoy conducts the experiment in a village in the Bolivian rainforest. The participants were asked to rate the pleasantness of various sounds, and Godoy recorded their response. Credit: Alan Schultz)

Why we like the music we do

In Western styles of music, from classical to pop, some combinations of notes are generally considered more pleasant than others. To most of our ears, a chord of C and G, for example, sounds much more agreeable than the grating combination of C and F# (which has historically been known as the “devil in music”).

For decades, neuroscientists have pondered whether this preference is somehow hardwired into our brains. A new study from MIT and Brandeis University suggests that the answer is no.

In a study of more than 100 people belonging to a remote Amazonian tribe with little or no exposure to Western music, the researchers found that dissonant chords such as the combination of C and F# were rated just as likeable as “consonant” chords, which feature simple integer ratios between the acoustical frequencies of the two notes.

“This study suggests that preferences for consonance over dissonance depend on exposure to Western musical culture, and that the preference is not innate,” says Josh McDermott, the Frederick A. and Carole J. Middleton Assistant Professor of Neuroscience in the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences at MIT.

McDermott and Ricardo Godoy, a professor at Brandeis University, led the study, which appeared in Nature on July 13. Alan Schultz, an assistant professor of medical anthropology at Baylor University, and Eduardo Undurraga, a senior research associate at Brandeis’ Heller School for Social Policy and Management, are also authors of the paper.

Consonance and dissonance

For centuries, some scientists have hypothesized that the brain is wired to respond favorably to consonant chords such as the fifth (so-called because one of the notes is five notes higher than the other). Musicians in societies dating at least as far back as the ancient Greeks noticed that in the fifth and other consonant chords, the ratio of frequencies of the two notes is usually based on integers — in the case of the fifth, a ratio of 3:2. The combination of C and G is often called “the perfect fifth.”

Others believe that these preferences are culturally determined, as a result of exposure to music featuring consonant chords. This debate has been difficult to resolve, in large part because nowadays there are very few people in the world who are not familiar with Western music and its consonant chords.

“It’s pretty hard to find people who don’t have a lot of exposure to Western pop music due to its diffusion around the world,” McDermott says. “Most people hear a lot of Western music, and Western music has a lot of consonant chords in it. It’s thus been hard to rule out the possibility that we like consonance because that’s what we’re used to, but also hard to provide a definitive test.”

In 2010, Godoy, an anthropologist who has been studying an Amazonian tribe known as the Tsimane for many years, asked McDermott to collaborate on a study of how the Tsimane respond to music. Most of the Tsimane, a farming and foraging society of about 12,000 people, have very limited exposure to Western music.

“They vary a lot in how close they live to towns and urban centers,” Godoy says. “Among the folks who live very far, several days away, they don’t have too much contact with Western music.”

The Tsimane’s own music features both singing and instrumental performance, but usually by only one person at a time.

Dramatic differences

The researchers did two sets of studies, one in 2011 and one in 2015. In each study, they asked participants to rate how much they liked dissonant and consonant chords. The researchers also performed experiments to make sure that the participants could tell the difference between dissonant and consonant sounds, and found that they could.

The team performed the same tests with a group of Spanish-speaking Bolivians who live in a small town near the Tsimane, and residents of the Bolivian capital, La Paz. They also tested groups of American musicians and nonmusicians.

“What we found is the preference for consonance over dissonance varies dramatically across those five groups,” McDermott says. “In the Tsimane it’s undetectable, and in the two groups in Bolivia, there’s a statistically significant but small preference. In the American groups it’s quite a bit larger, and it’s bigger in the musicians than in the nonmusicians.”

When asked to rate nonmusical sounds such as laughter and gasps, the Tsimane showed similar responses to the other groups. They also showed the same dislike for a musical quality known as acoustic roughness.

The findings suggest that it is likely culture, and not a biological factor, that determines the common preference for consonant musical chords, says Brian Moore, a professor of psychology at Cambridge University, who was not involved in the study.

“Overall, the results of this exciting and well-designed study clearly suggest that the preference for certain musical intervals of those familiar with Western music depends on exposure to that music and not on an innate preference for certain frequency ratios,” Moore says.

23 science facts we didn't know at the start of 2016

1. Gravitational waves are real. More than 100 years after Einstein first predicted them, researchers finally detected the elusive ripples in space time this year. We’ve now seen three gravitational wave events in total.

2. Sloths almost die every time they poop, and it looks agonising.

3. It’s possible to live for more than a year without a heart in your body.

4. It’s also possible to live a normal life without 90 percent of your brain.

5. There are strange, metallic sounds coming from the Mariana trench, the deepest point on Earth’s surface. Scientists currently think the noise is a new kind of baleen whale call.

6. A revolutionary new type of nuclear fusion machine being trialled in Germany really works, and could be the key to clean, unlimited energy.

7. There’s an Earth-like planet just 4.2 light-years away in the Alpha Centauri star system - and scientists are already planning a mission to visit it.

8. Earth has a second mini-moon orbiting it, known as a ‘quasi-satellite’. It’s called 2016 HO3.

9. There might be a ninth planet in our Solar System (no, Pluto doesn’t count).

10. The first written record demonstrating the laws of friction has been hiding inside Leonardo da Vinci’s “irrelevant scribbles” for the past 500 years.

11. Zika virus can be spread sexually, and it really does cause microcephaly in babies.

12. Crows have big ears, and they’re kinda terrifying.

13. The largest known prime number is 274,207,281– 1, which is a ridiculous 22 million digits in length. It’s 5 million digits longer than the second largest prime.

14. The North Pole is slowly moving towards London, due to the planet’s shifting water content.

15. Earth lost enough sea ice this year to cover the entire land mass of India.

16. Artificial intelligence can beat humans at Go.

17. Tardigrades are so indestructible because they have an in-built toolkit to protect their DNA from damage. These tiny creatures can survive being frozen for decades, can bounce back from total desiccation, and can even handle the harsh radiation of space.

18. There are two liquid states of water.

19. Pear-shaped atomic nuclei exist, and they make time travel seem pretty damn impossible.

20. Dinosaurs had glorious tail feathers, and they were floppy.

21. One third of the planet can no longer see the Milky Way from where they live.

22. There’s a giant, 1.5-billion-cubic-metre (54-billion-cubic-foot) field of precious helium gas in Tanzania.

23. The ‘impossible’ EM Drive is the propulsion system that just won’t quit. NASA says it really does seem to produce thrust - but they still have no idea how. We’ll save that mystery for 2017.

-

madlyesmith reblogged this · 5 years ago

madlyesmith reblogged this · 5 years ago -

shanstudies reblogged this · 6 years ago

shanstudies reblogged this · 6 years ago -

lizardmelon liked this · 6 years ago

lizardmelon liked this · 6 years ago -

day-knight reblogged this · 6 years ago

day-knight reblogged this · 6 years ago -

notjanine liked this · 6 years ago

notjanine liked this · 6 years ago -

herbaltea-studies reblogged this · 6 years ago

herbaltea-studies reblogged this · 6 years ago -

biopsychs reblogged this · 6 years ago

biopsychs reblogged this · 6 years ago -

tuscanlthr reblogged this · 6 years ago

tuscanlthr reblogged this · 6 years ago -

mille-preakers reblogged this · 6 years ago

mille-preakers reblogged this · 6 years ago -

theosaretinsaga reblogged this · 6 years ago

theosaretinsaga reblogged this · 6 years ago -

starof464 reblogged this · 6 years ago

starof464 reblogged this · 6 years ago -

a-sad-fat-dragon-with-no-friends reblogged this · 6 years ago

a-sad-fat-dragon-with-no-friends reblogged this · 6 years ago -

billthepanda liked this · 6 years ago

billthepanda liked this · 6 years ago -

probablyanerd-mostlikelyanerd liked this · 6 years ago

probablyanerd-mostlikelyanerd liked this · 6 years ago -

kirkwahammett-blog1 liked this · 6 years ago

kirkwahammett-blog1 liked this · 6 years ago -

puzzler liked this · 6 years ago

puzzler liked this · 6 years ago -

llort liked this · 6 years ago

llort liked this · 6 years ago -

miai091108-blog liked this · 6 years ago

miai091108-blog liked this · 6 years ago -

ghostlyjudgestudentslime-blog liked this · 6 years ago

ghostlyjudgestudentslime-blog liked this · 6 years ago -

papaluvin420 liked this · 6 years ago

papaluvin420 liked this · 6 years ago -

wtfdotti liked this · 6 years ago

wtfdotti liked this · 6 years ago -

davidcustiskimball reblogged this · 6 years ago

davidcustiskimball reblogged this · 6 years ago -

adventuresinaberdeen liked this · 6 years ago

adventuresinaberdeen liked this · 6 years ago -

mencar13-blog liked this · 6 years ago

mencar13-blog liked this · 6 years ago -

nonoevil reblogged this · 6 years ago

nonoevil reblogged this · 6 years ago -

infinite-genesis reblogged this · 6 years ago

infinite-genesis reblogged this · 6 years ago -

becckali-blog liked this · 6 years ago

becckali-blog liked this · 6 years ago -

goldgurufu liked this · 6 years ago

goldgurufu liked this · 6 years ago

A pharmacist and a little science sideblog. "Knowledge belongs to humanity, and is the torch which illuminates the world." - Louis Pasteur

215 posts