Bismuth Is One Of The Weirdest-looking Elements On The Periodic Table, But Its Internal Properties Just

Bismuth is one of the weirdest-looking elements on the Periodic Table, but its internal properties just got even stranger. Scientists have discovered that at a fraction of a degree above absolute zero (-273.15°C), bismuth becomes a superconductor - a material that can conduct electricity without resistance.

According to the current theory of superconductivity, that doesn’t make a whole lot of sense, because for 40 years now, scientists have assumed that superconducting materials must be abundant in free-flowing mobile electrons. But in bismuth, there’s just one mobile electron for every 100,000 atoms.

“In general, compounds that exhibit superconductivity have roughly one mobile electron per atom,” Srinivasan Ramakrishnan from the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research in India explained to Chemistry World.

“However, in bismuth, one mobile electron is shared by 100,000 atoms – since [the] carrier density is so small, people did not believe bismuth will superconduct.”

Continue Reading.

More Posts from Contradictiontonature and Others

“Sixth sense” may be more than just a feeling

With the help of two young patients with a unique neurological disorder, an initial study by scientists at the National Institutes of Health suggests that a gene called PIEZO2 controls specific aspects of human touch and proprioception, a “sixth sense” describing awareness of one’s body in space. Mutations in the gene caused the two to have movement and balance problems and the loss of some forms of touch. Despite their difficulties, they both appeared to cope with these challenges by relying heavily on vision and other senses.

“Our study highlights the critical importance of PIEZO2 and the senses it controls in our daily lives,” said Carsten G. Bönnemann, M.D., senior investigator at the NIH’s National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and a co-leader of the study published in the New England Journal of Medicine. “The results establish that PIEZO2 is a touch and proprioception gene in humans. Understanding its role in these senses may provide clues to a variety of neurological disorders.”

Dr. Bönnemann’s team uses cutting edge genetic techniques to help diagnose children around the world who have disorders that are difficult to characterize. The two patients in this study are unrelated, one nine and the other 19 years old. They have difficulties walking; hip, finger and foot deformities; and abnormally curved spines diagnosed as progressive scoliosis.

Working with the laboratory of Alexander T. Chesler, Ph.D., investigator at NIH’s National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), the researchers discovered that the patients have mutations in the PIEZO2 gene that appear to block the normal production or activity of Piezo2 proteins in their cells. Piezo2 is what scientists call a mechanosensitive protein because it generates electrical nerve signals in response to changes in cell shape, such as when skin cells and neurons of the hand are pressed against a table. Studies in mice suggest that Piezo2 is found in the neurons that control touch and proprioception.

“As someone who studies Piezo2 in mice, working with these patients was humbling,” said Dr. Chesler. “Our results suggest they are touch-blind. The patient’s version of Piezo2 may not work, so their neurons cannot detect touch or limb movements.”

Further examinations at the NIH Clinical Center suggested the young patients lack body awareness. Blindfolding them made walking extremely difficult, causing them to stagger and stumble from side to side while assistants prevented them from falling. When the researchers compared the two patients with unaffected volunteers, they found that blindfolding the young patients made it harder for them to reliably reach for an object in front of their faces than it was for the volunteers. Without looking, the patients could not guess the direction their joints were being moved as well as the control subjects could.

The patients were also less sensitive to certain forms of touch. They could not feel vibrations from a buzzing tuning fork as well as the control subjects could. Nor could they tell the difference between one or two small ends of a caliper pressed firmly against their palms. Brain scans of one patient showed no response when the palm of her hand was brushed.

Nevertheless, the patients could feel other forms of touch. Stroking or brushing hairy skin is normally perceived as pleasant. Although they both felt the brushing of hairy skin, one claimed it felt prickly instead of the pleasant sensation reported by unaffected volunteers. Brain scans showed different activity patterns in response to brushing between unaffected volunteers and the patient who felt prickliness.

Despite these differences, the patients’ nervous systems appeared to be developing normally. They were able to feel pain, itch, and temperature normally; the nerves in their limbs conducted electricity rapidly; and their brains and cognitive abilities were similar to the control subjects of their age.

“What’s remarkable about these patients is how much their nervous systems compensate for their lack of touch and body awareness,” said Dr. Bönnemann. “It suggests the nervous system may have several alternate pathways that we can tap into when designing new therapies.”

Previous studies found that mutations in PIEZO2 may have various effects on the Piezo2 protein that may result in genetic musculoskeletal disorders, including distal arthrogryposis type 5, Gordon Syndrome, and Marden-Walker Syndrome. Drs. Bönnemann and Chesler concluded that the scoliosis and joint problems of the patients in this study suggest that Piezo2 is either directly required for the normal growth and alignment of the skeletal system or that touch and proprioception indirectly guide skeletal development.

“Our study demonstrates that bench and bedside research are connected by a two-way street,” said Dr. Chesler. “Results from basic laboratory research guided our examination of the children. Now we can take that knowledge back to the lab and use it to design future experiments investigating the role of PIEZO2 in nervous system and musculoskeletal development.”

Network Lost

If you believe the theory of six degrees of separation, we’re all connected to each other (and possibly to Kevin Bacon) by common friends and friend-of-friends. It might feel like a small world – in fact, these patterns crops up in all sorts of places. Small world networks connect distant brain cells, and help these lymph nodes (outlined in grey) fight infections. A network of fibroblastic reticular cells (FRCs, red) spreads out inside each node, producing chemicals (green) to support immune cells while they zip around the node gathering antigens – chemical information used to target bacteria. These mouse lymph nodes are treated with different doses of a toxin that destroys FRC networks. A high dose crumples the lymph node in the bottom right. Amazingly, many of these networks repair themselves, showing just how committed immune defences are to keeping their small worlds alive.

Written by John Ankers

Image from work by Mario Novkovic, Lucas Onder and Jovana Cupovic, and colleagues

Institute of Immunobiology, Kantonsspital St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland

Image originally published under a Creative Commons Licence (BY 4.0)

Published in PLOS Biology, July 2016

You can also follow BPoD on Twitter and Facebook

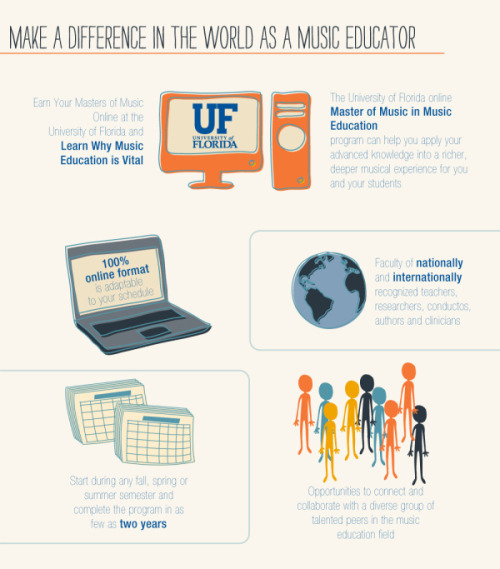

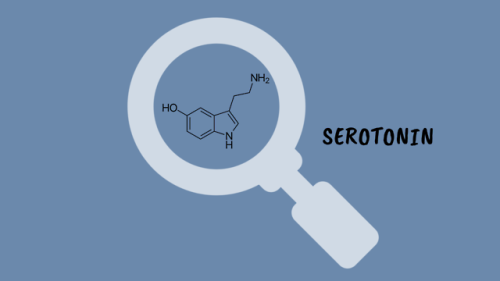

How Do Antidepressants Work? (Video)

Your brain is a network of billions of neurones, all somehow connected to each other. At this very second, millions of impulses are being transmitted through these connections carrying information about what you can see and hear, as well as your emotional state. It’s an incredibly complex system but sometimes things go wrong. Despite extensive research, we are still not certain on the biology that underlies mental illnesses- including depression. However, we have come pretty far in developing effective treatments.

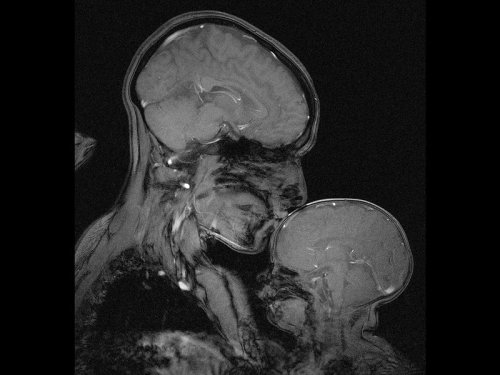

Neuroscientist captures an MRI of a mother and child

Professor Rebecca Saxe (MIT) has taken the first ever MR image of a mother and child.

“This picture is an MR image of a mother and a child that I made in my lab at MIT. You might see it as sweet and touching… an image of universal love. We can’t see clothes or hairstyles or even skin colour. From what we do see, the biology and the brains, this could be any mother and child or even father and child at any time and place in history; having an experience that any human can recognise.

Or you might see it as disturbing, a reminder that our human bodies are much too fragile as houses for ourselves. MRI’s are usually medical images and often bad news. Each white spot in that picture is a blood vessel that could clog, each tiny fold of those brains could harbour a tumour. The baby’s brain maybe looks particularly vulnerable pressed against the soft thin shell of its skull.

I see those things, universal emotions and frightening fragility but I also see one of the most amazing transformations in biology.”

Quotes have been taken from a TEDx talk given by Professor Saxe explaining the story behind the above picture.

A special organic dye, Nile Red in different solvents.

From left to right I dissolved equal amounts of Nile Red (a dye) in different solvents. The solvents were: methanol, diisopropyl ether, hexane, n-propanol, tetrahydrofuran, toluene, ethanol, acetone.

Depending on the solvents polarity, the dye dissolved to give different colored solutions (upper image), this is called solvatochromism. It is the ability of a chemical substance to change color due to a change in solvent polarity.

Under UV light, these solutions emitted different colors (bottom pics), this is called solvatofluorescence. The emission and excitation wavelength both shift depending on solvent polarity, so it fluoresces with different color depending on the solvent what it’s dissolved in.

Nile Red is a quite expensive dye, which costs a bit over 1000 USD/gram, therefore I had to make it. The purification of the raw material was posted HERE.

To help the blog, donate to Labphoto through Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/labphoto

Thorny life of new-born neurons

Even in adult brains, new neurons are generated throughout a lifetime. In a publication in the scientific journal PNAS, a research group led by Goethe University describes plastic changes of adult-born neurons in the hippocampus, a critical region for learning: frequent nerve signals enlarge the spines on neuronal dendrites, which in turn enables contact with the existing neural network.

Practise makes perfect, and constant repetition promotes the ability to remember. Researchers have been aware for some time that repeated electrical stimulation strengthens neuron connections (synapses) in the brain. It is similar to the way a frequently used trail gradually widens into a path. Conversely, if rarely used, synapses can also be removed – for example, when the vocabulary of a foreign language is forgotten after leaving school because it is no longer practised. Researchers designate the ability to change interconnections permanently and as needed as the plasticity of the brain.

Plasticity is especially important in the hippocampus, a primary region associated with long-term memory, in which new neurons are formed throughout life. The research groups led by Dr Stephan Schwarzacher (Goethe University), Professor Peter Jedlicka (Goethe University and Justus Liebig University in Gießen) and Dr Hermann Cuntz (FIAS, Frankfurt) therefore studied the long-term plasticity of synapses in new-born hippocampal granule cells. Synaptic interconnections between neurons are predominantly anchored on small thorny protrusions on the dendrites called spines. The dendrites of most neurons are covered with these spines, similar to the thorns on a rose stem.

In their recently published work, the scientists were able to demonstrate for the first time that synaptic plasticity in new-born neurons is connected to long-term structural changes in the dendritic spines: repeated electrical stimulation strengthens the synapses by enlarging their spines. A particularly surprising observation was that the overall size and number of spines did not change: when the stimulation strengthened a group of synapses, and their dendritic spines enlarged, a different group of synapses that were not being stimulated simultaneously became weaker and their dendritic spines shrank.

“This observation was only technically possible because our students Tassilo Jungenitz and Marcel Beining succeeded for the first time in examining plastic changes in stimulated and non-stimulated dendritic spines within individual new-born cells using 2-photon microscopy and viral labelling,” says Stephan Schwarzacher from the Institute for Anatomy at the University Hospital Frankfurt. Peter Jedlicka adds: “The enlargement of stimulated synapses and the shrinking of non-stimulated synapses was at equilibrium. Our computer models predict that this is important for maintaining neuron activity and ensuring their survival.”

The scientists now want to study the impenetrable, spiny forest of new-born neuron dendrites in detail. They hope to better understand how the equilibrated changes in dendritic spines and their synapses contribute the efficient storing of information and consequently to learning processes in the hippocampus.

Anti-microbial Peptides: Proteins that Pack a Punch

Antimicrobial resistance is a growing concern and it is currently estimated that approximately 2 million people are infected annually with serious infections that show antibiotic resistance to some degree. This contributes to the mortality of 23, 000 people with many more suffering severe complications as a direct result of antibiotic resistant infections. The economic burden on the US is thought to exceed $20 billion simply on health care bills alone, and a further $35 billion due to a societal loss in work based productivity (1).

The spread of antibiotic resistance is now widely believed to be a direct result of the anthropogenic release of antibiotics into the biosphere. We are now faced with the dilemma of how to treat these infections. In previous articles, I’ve talked largely about bacteriophages and how they are one possible solution to this complex problem. This article will introduce you to another class of antimicrobial agents, aptly called antimicrobial peptides (AMPs).

What are Antimicrobial Peptides?

Proteins are found ubiquitously throughout all cellular life and are like the mechanical parts of a car, helping your cells carry out a vast array of functions every single day. Peptides are small proteins that contain two or more amino acids joined by peptide bonds. Anyone who is familiar with biochemistry will be aware of the sheer diversity found amongst these versatile molecules. Needless to say, it should not be surprising that there are a large class of proteins involved in offensive cellular warfare. They are found widely in all domains of life and have evolved to give a cell a competitive advantage over its nastier neighbours.

Without getting too bogged down with the biochemistry, AMPs are characterised by their overall properties. AMPs that share common structural features will also have a similar function when targeting a cell. The diversity amongst these proteins can be seen in Figure 1, which shows some examples from the four classes of AMPs. The class I AMPs, the lantibiotics for example, all contain similar motifs which assign them a similar job. AMPs can range from anywhere between 6 to >59 amino acids, but are generally considered to be small proteins (2). They generally have a rather amphipathic nature and feature both positive and negative charges.

These peptides may have a number of rare (Figure 1), modified amino acids. The lanthionines are a class of AMP that contain lanthionine rings made from dehydrated serine and threonine residues connected by thioether cross-links. This happens after the protein leaves the ribosome and gives the protein some very unique properties which will be explained later in the article (3).

Figure 1. The four classes of AMPs, showing common examples in each class. Rare, modified amino acids are indicated by coloured circles with the three letter codes indicating the name of the residue. Thioether cross-links are indicated by an S coordinated by two black lines (3).

Implications for the Pharmaceutical industry

Our antibiotic pipeline is drying up (Figure 2), with few new drugs being approved by the Food and Drug Administration. Identifying novel antibiotics is a tedious process that requires a lot of time and effort from drug companies, which they are not willing to do. The reason for this boils down to economic reasons, as antibiotics are just not worth the investment. Unlike other drugs such as statins, antibiotics are only used for short periods of time by a patient. One course of treatment therefore doesn’t return a massive profit for the company. The second issue antibiotics face is that resistance to them occurs rapidly after they are put into circulation, so the company is not likely to get much use out of the drug. Therefore we need to find a new source for our antimicrobials. This is where the AMPs come in.

Currently, nearly 900 AMPs have been identified and characterised with many more undiscovered (2). They are an untapped source of drug discovery and they exhibit numerous benefits over their antibiotic cousins. As they are proteins, they have a genetic origin, which could provide an amenable platform for further development through random mutagenesis. This could produce a vast library of antimicrobial compounds (4,5), drastically improving our options for therapy.

Figure 2. Graph showing the steady decline in antibiotic development from 1980 to 2012 (1)

Nisin; not so nice if you’re a bacterial cell

AMPs were discovered in the 1930s although their use in the health industry has been fairly limited, resulting from the sheer difficulty and cost of manufacturing and purifying proteins on a large scale. The bacterially produced lantibiotics are by far the most well studied AMPs and have the most potential for the pharmaceutical industry. Nisin (E234) is the most well studied lantibiotic (Refer to Figure 1, Class I) and is produced by the bacterium Lactococcus lactis (6).

It shows broad spectrum activity on a large number of Gram-positive bacteria including other lactic acid bacteria, which has made it a coveted preservative in food processing. Currently it is added to cheeses, meats and beverages to extend shelf life and prevent the growth of spoilage organisms including spore forming bacteria such as Clostridium botulinum (6). The lantibiotics have also proven their capabilities for treating the clinically relevant pathogens methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (7). They are also seen to have similar levels of activity as antibiotics and express low levels of toxicity to mammalian cells. Nisin exhibits poor oral availability making it more appealing as a topical agent or for intravenous application but there are also intentions to use it as a sterilising agent for catheters and medical equipment to help reduce the risk of infection (3).

So could lantibiotics like nisin be a good solution to antimicrobial resistance? Well more compelling evidence for nisin is that resistance has not been thoroughly documented. Nisin has been applied in sub-therapeutic concentrations in the food industry since the 1960s but still mostly retains its bactericidal ability. Resistance has been achieved artificially in the lab (discussed later in the article), but due to the mechanism of some lantibiotics including nisin, resistance is thought to be unlikely (6).

The mechanism behind nisin’s potency

Unlike animal cells, generally bacterial membranes have an overall negative charge and lack cholesterol (8). Nisin contains a high proportion of the positively charged (basic) amino acids lysine and arginine. These positive charges allow the protein to interact with the negative charges commonly associated with bacterial cell membranes (2). Nisin is good at aligning against Gram-positive bacterial membranes, where they multimerise to form short-lived pores (Figure 3). Hydrophobic regions help the protein to insert into the membrane and stabilise the pore (2), which allows the transport of ATP, ions and amino acids, eliminating the cellular membrane potential (9).

Nisin has a second trick up its sleeve. Its C-terminal, the portion of the protein containing the lanthionine ring motifs, allows it to latch onto the important membrane component lipid II (Figure 3). Lipid II is a precursor for peptidoglycan; the cell wall strengthening polymer found in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. It is a common target for antibiotics including penicillin and vancomycin, which both target different stages of its synthesis. It helps to maintain the cell structure and prevents it from bursting under high osmotic pressure. When nisin binds to lipid II, it sequesters this molecule from the enzymes that catalyse its addition to growing peptidoglycan chains. Binding lipid II also helps to stabilise the transmembrane pores, further damaging the cell. As a result, not only is the cell wall weakened, but the cell loses its metabolic capabilities, through the loss of charged molecules.

The dual targeting system of nisin is thought to be the reason why resistance to nisin has not be well documented (10). The two processes are completely physiologically separate, and therefore to develop resistance, the bacteria would have to develop two unrelated mutations to counteract the effects of nisin.

Figure 3. Diagram showing the mechanism of several lantibiotics including nisin. AMPs are represented by lines made with clear circles. Phospholipids represented by green circles with tails. Lipid II is represented by orange hexagons (3).

What do we know about resistance towards nisin?

There are several proposed means by which an organism can be resistance to a toxin. Firstly, an organism may have innate immunity to a toxin simply because of its physiology. We see this largely in the Gram-negative bacteria towards nisin. The lipopolysaccharide (LPS) layer found on the outside of their cell wall provides protection against nisin and it has been shown that the oligosaccharides found within the core region of this structure greatly improve protection against nisin. It is believed that this is because metal ions are sequestered within this layer, adding additional positive charges to the site. Such charges would help to prevent nisin from aligning with the cell membrane (11). Removing these metal ions by sequestering them sensitises Gram-negative bacteria to nisin.

Emergent resistance is the type of resistance that should concern us the most, as it is the reason why we are now faced with the problem of antimicrobial resistance. It involves the acquisition of mutations or DNA that help confer tolerance to stress resulting from the action of a toxin (12). Although currently only produced in the laboratory, experiments carried out on the tolerance of clinically relevant bacteria towards nisin are crucial in highlighting the future of implementing an antimicrobial.

Resistance mechanisms have been documented in several bacteria including the causative agent of listeriosis, Listeria monocytogenes. Although not fully understood, changes in membrane composition have been attributed for the decreased susceptibility in resistant strains. In resistant strains, the bacterial membrane is composed of less negatively charged phospholipids. Similarly to sequestering metal ions near the membrane, this alters the overall net charge, helping to repel nisin.

The number of long chain fatty acids within its membrane is increased helping to reducing fluidity. This is believed to play a role in preventing nisin from inserting itself into the membrane. Studies show that nisin resistant strains were also less susceptible to cell wall acting components such as lysozyme and cell wall acting antibiotics. They did not identify the phenotypic change that gave additional protection, but this does indicate that a number of defence mechanisms are involved in defending cells against environmental stress from nisin (13).

Conclusion:

So could AMPs like nisin possibly serve as a replacement to our current armamentarium of antibiotics? AMPs are a largely untapped source of antimicrobials with many more still to be identified. AMPs may therefore serve as a new source of antimicrobials to help relieve the stress exerted on microorganisms by antibiotics. We have seen that nisin is an effective antimicrobial against a wide range of Gram-positive bacteria including spore forming bacteria. The dual-action of nisin challenges bacterial cells making it difficult for them to develop resistance. However, lab-based experiments have shown that it is possible to generate resistant strains showing the tenacity of bacteria to adapt to such potent environmental stresses. To learn from our previous mistakes with antibiotics, more responsible practices would need to be applied. Using combination therapy or rotating drug usage, as done with pesticides, could help further prevent resistance. Where they are likely to be applied in high concentration (in medical settings and agriculture), combination therapies should be used to further reduce the likelihood of resistance.

1. CDC. Antibiotic resistance threats. US Dep Healh Hum Serv. 2013;22–50.

2. Brogden KA. Antimicrobial peptides: pore formers or metabolic inhibitors in bacteria? Nat Rev Microbiol [Internet]. 2005;3(3):238–50. Available from: http://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/nrmicro1098

3. Dischinger J, Basi Chipalu S, Bierbaum G. Lantibiotics: Promising candidates for future applications in health care. Int J Med Microbiol [Internet]. Elsevier GmbH.; 2014;304(1):51–62. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmm.2013.09.003

4. Field D, Begley M, O’Connor PM, Daly KM, Hugenholtz F, Cotter PD, et al. Bioengineered Nisin A Derivatives with Enhanced Activity against Both Gram Positive and Gram Negative Pathogens. PLoS One. 2012;7(10).

5. Hilpert K, Volkmer-Engert R, Walter T, Hancock REW. High-throughput generation of small antibacterial peptides with improved activity. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23(8):1008–12.

6. van Heel AJ, Montalban-Lopez M, Kuipers OP. Evaluating the feasibility of lantibiotics as an alternative therapy against bacterial infections in humans. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2011;7(6):675–80.

7. Barbosa J, Caetano T, Mendo S. Class I and Class II Lanthipeptides Produced by Bacillus spp. J Nat Prod [Internet]. 2015;151008121848005. Available from: http://pubsdc3.acs.org/doi/10.1021/np500424y

8. Neumann A, Berends ETM, Nerlich A, Molhoek EM, Gallo RL, Meerloo T, et al. The antimicrobial peptide LL-37 facilitates the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. Biochem J [Internet]. 2014 Nov 15 [cited 2014 Oct 28];464(1):3–11. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25181554

9. Kordel M, Schuller F, Sahl HG. Interaction of the pore forming-peptide antibiotics Pep 5, nisin and subtilin with non-energized liposomes. FEBS Lett. 1989;244(1):99–102.

10. Islam MR, Nagao J, Zendo T, Sonomoto K. Antimicrobial mechanism of lantibiotics. Biochem Soc Trans [Internet]. 2012;40(6):1528–33. Available from: http://www.biochemsoctrans.org/bst/040/bst0401528.htm

11. Stevens K a., Sheldon BW, Klapes N a., Klaenhammer TR. Nisin treatment for inactivation of Salmonella species and other gram- negative bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57(12):3613–5.

12. Kaur G, Malik RK, Mishra SK, Singh TP, Bhardwaj A, Singroha G, et al. Nisin and class IIa bacteriocin resistance among Listeria and other Foodborne pathogens and spoilage bacteria. Microb Drug Resist. 2011;17(2).

13. Crandall AD, Montville TJ. Nisin resistance in Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 700302 is a complex phenotype. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998

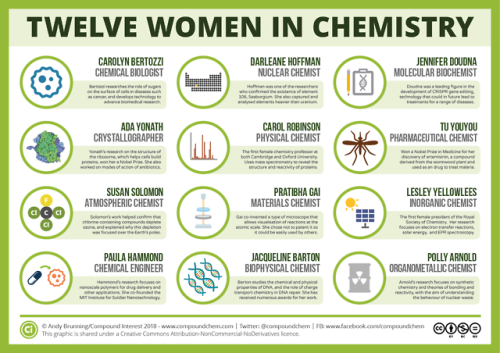

For International Women’s Day, here are 12 women from chemistry history: wp.me/p4aPLT-2ra and 12 from chemistry present: wp.me/p4aPLT-5w7

-

applauseforsally liked this · 8 years ago

applauseforsally liked this · 8 years ago -

dapperkillerwhale2222 reblogged this · 8 years ago

dapperkillerwhale2222 reblogged this · 8 years ago -

the-psychic-paligin reblogged this · 8 years ago

the-psychic-paligin reblogged this · 8 years ago -

concerned-relatives reblogged this · 8 years ago

concerned-relatives reblogged this · 8 years ago -

astroanarchy reblogged this · 8 years ago

astroanarchy reblogged this · 8 years ago -

555-evil-gnomes reblogged this · 8 years ago

555-evil-gnomes reblogged this · 8 years ago -

brokentowels liked this · 8 years ago

brokentowels liked this · 8 years ago -

unwitnessed liked this · 8 years ago

unwitnessed liked this · 8 years ago -

agayconcept reblogged this · 8 years ago

agayconcept reblogged this · 8 years ago -

agayconcept liked this · 8 years ago

agayconcept liked this · 8 years ago -

last-hag liked this · 8 years ago

last-hag liked this · 8 years ago -

moonspren liked this · 8 years ago

moonspren liked this · 8 years ago -

queenlabonte-blog liked this · 8 years ago

queenlabonte-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

queer-z0mbies liked this · 8 years ago

queer-z0mbies liked this · 8 years ago -

littleclouds reblogged this · 8 years ago

littleclouds reblogged this · 8 years ago -

jsrocks reblogged this · 8 years ago

jsrocks reblogged this · 8 years ago -

canadianabroadvery liked this · 8 years ago

canadianabroadvery liked this · 8 years ago -

idonotliketheconeofshamesblog reblogged this · 8 years ago

idonotliketheconeofshamesblog reblogged this · 8 years ago -

idonotliketheconeofshamesblog liked this · 8 years ago

idonotliketheconeofshamesblog liked this · 8 years ago -

theuseofashes reblogged this · 8 years ago

theuseofashes reblogged this · 8 years ago -

dammar reblogged this · 8 years ago

dammar reblogged this · 8 years ago -

kinkyfinky12-blog liked this · 8 years ago

kinkyfinky12-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

thoths-foundry-blog reblogged this · 8 years ago

thoths-foundry-blog reblogged this · 8 years ago -

lattendicht reblogged this · 8 years ago

lattendicht reblogged this · 8 years ago -

thefourthpurpleone liked this · 8 years ago

thefourthpurpleone liked this · 8 years ago -

chaointe reblogged this · 8 years ago

chaointe reblogged this · 8 years ago -

chaointe liked this · 8 years ago

chaointe liked this · 8 years ago -

nanophile liked this · 8 years ago

nanophile liked this · 8 years ago -

what-is-sociallife reblogged this · 8 years ago

what-is-sociallife reblogged this · 8 years ago -

kobayashii-maru liked this · 8 years ago

kobayashii-maru liked this · 8 years ago -

jennaann2017-blog liked this · 8 years ago

jennaann2017-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

elithegr8 liked this · 8 years ago

elithegr8 liked this · 8 years ago -

ministryofsillykisses liked this · 8 years ago

ministryofsillykisses liked this · 8 years ago -

astrangekindofhistory-blog liked this · 8 years ago

astrangekindofhistory-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

leafy-leifster reblogged this · 8 years ago

leafy-leifster reblogged this · 8 years ago -

taillessthedragon liked this · 8 years ago

taillessthedragon liked this · 8 years ago -

5idestuff liked this · 8 years ago

5idestuff liked this · 8 years ago

A pharmacist and a little science sideblog. "Knowledge belongs to humanity, and is the torch which illuminates the world." - Louis Pasteur

215 posts