A Wispy And Filamentary Cloud Of Gas And Dust, The Crab Nebula Is The Remnant Of A Supernova Explosion

A wispy and filamentary cloud of gas and dust, the Crab nebula is the remnant of a supernova explosion that was observed by Chinese astronomers in the year 1054.

The image combines Hubble’s view of the nebula at visible wavelengths, obtained using three different filters sensitive to the emission from oxygen and sulphur ions and is shown here in blue. Herschel’s far-infrared image reveals the emission from dust in the nebula and is shown here in red.

Credit: NASA/ESA/Hubble

More Posts from Xyhor-astronomy and Others

Resupply Mission Brings Mealworms and Mustard Seeds to Space Station

Orbital ATK will launch its Cygnus cargo spacecraft to the International Space Station on November 11, 2017 from Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia. It will be packed with cargo and scientific experiments for the six humans currently living and working on the orbiting laboratory.

The cargo spacecraft is named the S.S. Gene Cernan after former NASA astronaut Eugene Cernan, who is the last man to have walked on the moon.

Here are some of the really neat science and research experiments that will be delivered to the station:

What’s Microgravity Got to do with Bacterial Antibiotics?

Antibiotic resistance could pose a danger to astronauts, especially since microgravity has been shown to weaken human immune response. E. coli AntiMicrobial Satellite (EcAMSat) will study microgravity’s effect on bacterial antibiotic resistance.

Results from this experiment could help us determine appropriate antibiotic dosages to protect astronaut health during long-duration human spaceflight and help us understand how antibiotic effectiveness may change as a function of stress on Earth.

Laser Beams…Not on Sharks…But on a CubeSat

Traditional laser communication systems use transmitters that are far too large for small spacecraft. The Optical Communication Sensor Demonstration (OCSD) tests the functionality of laser-based communications using CubeSats that provide a compact version of the technology.

Results from OCSD could lead to improved GPS and other satellite networks on Earth and a better understanding of laser communication between small satellites in low-Earth orbit.

This Hybrid Solar Antenna Could Make Space Communication Even Better

As space exploration increases, so will the need for improved power and communication technologies. The Integrated Solar Array and Reflectarray Antenna (ISARA), a hybrid power and communication solar antenna that can send and receive messages, tests the use of this technology in CubeSat-based environmental monitoring.

ISARA may provide a solution for sending and receiving information to and from faraway destinations, both on Earth and in space.

More Plants in Space!

Ready for a mouthful…The Biological Nitrogen Fixation in Microgravity via Rhizobium-Legume Symbiosis…aka the Biological Nitrogen Fixation experiment, will examine how low-gravity conditions affect the nitrogen fixation process of the Microclover legume (a plant in the pea family). Nitrogen fixation is a process where nitrogen in the atmosphere is converted into ammonia. This crucial element of any ecosystem is also a natural fertilizer that is necessary for most types of plant growth.

This experiment could tell us about the space viability of the legume’s ability to use and recycle nutrients and give researchers a better understanding of this plant’s potential uses on Earth.

What Happens When Mealworms Live in Space?

Mealworms are high in nutrients and one of the most popular sources of alternative protein in developing countries. The Effects of Microgravity on the Life Cycle of Tenebrio Molitor (Tenebrio Molitor) investigation studies how the microgravity environment affects the mealworm life cycle.

In addition to alternative protein research, this investigation will provide information about animal growth under unique conditions.

Mustard Seeds in Microgravity

The Life Cycle of Arabidopsis thaliana in Microgravity experiment studies the formation and functionality of the Arabidopsis thaliana, a mustard plant with a genome that is fully mapped, in microgravity conditions.

The results from this investigation could contribute to an understanding of plant and crop growth in space.

Follow @ISS_Research on Twitter for more information about the science happening on space station.

Watch the launch live HERE on Nov. 11, liftoff is scheduled for 7:37 a.m. EDT!

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com.

What are brown dwarfs?

In order to understand what is a brown dwarf, we need to understand the difference between a star and a planet. It is not easy to tell a star from a planet when you look up at the night sky with your eyes. However, the two kinds of objects look very different to an astronomer using a telescope or spectroscope. Planets shine by reflected light; stars shine by producing their own light. So what makes some objects shine by themselves and other objects only reflect the light of some other body? That is the important difference to understand – and it will allow us to understand brown dwarfs as well.

As a star forms from a cloud of contracting gas, the temperature in its center becomes so large that hydrogen begins to fuse into helium – releasing an enormous amount of energy which causes the star to begin shining under its own power. A planet forms from small particles of dust left over from the formation of a star. These particles collide and stick together. There is never enough temperature to cause particles to fuse and release energy. In other words, a planet is not hot enough or heavy enough to produce its own light.

Brown dwarfs are objects which have a size between that of a giant planet like Jupiter and that of a small star. In fact, most astronomers would classify any object with between 13 times the mass of Jupiter and 75 times the mass of Jupiter to be a brown dwarf. Given that range of masses, the object would not have been able to sustain the fusion of hydrogen like a regular star; thus, many scientists have dubbed brown dwarfs as “failed stars”.

A Trio of Brown Dwarfs

This artist’s conception illustrates what brown dwarfs of different types might look like to a hypothetical interstellar traveler who has flown a spaceship to each one. Brown dwarfs are like stars, but they aren’t massive enough to fuse atoms steadily and shine with starlight – as our sun does so well.

On the left is an L dwarf, in the middle is a T dwarf, and on the right is a Y dwarf. The objects are progressively cooler in atmospheric temperatures as you move from left to right. Y dwarfs are the newest and coldest class of brown dwarfs and were discovered by NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or WISE. WISE was able to detect these Y dwarfs for the first time because it surveyed the entire sky deeply at the infrared wavelengths at which these bodies emit most of their light. The L dwarf is seen as a dim red orb to the eye. The T dwarf is even fainter and appears with a darker reddish, or magenta, hue. The Y dwarf is dimmer still. Because astronomers have not yet detected Y dwarfs at the visible wavelengths we see with our eyes, the choice of a purple hue is done mainly for artistic reasons. The Y dwarf is also illustrated as reflecting a faint amount of visible starlight from interstellar space.

In this rendering, the traveler’s spaceship is the same distance from each object. This illustrates an unusual property of brown dwarfs – that they all have the same dimensions, roughly the size of the planet Jupiter, regardless of their mass. This mass disparity can be as large as fifteen times or more when comparing an L to a Y dwarf, despite the fact that both objects have the same radius. The three brown dwarfs also have very different atmospheric temperatures. A typical L dwarf has a temperature of 2,600 degrees Fahrenheit (1,400 degrees Celsius). A typical T dwarf has a temperature of 1,700 degrees Fahrenheit (900 degrees Celsius). The coldest Y dwarf so far identified by WISE has a temperature of less than about 80 degrees Fahrenheit (25 degrees Celsius).

Sources: starchild.gsfc.nasa.gov & nasa.gov

image credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

Shadow Veil by Abi Ashra (Tumblr)

Meteor impact craters of the world

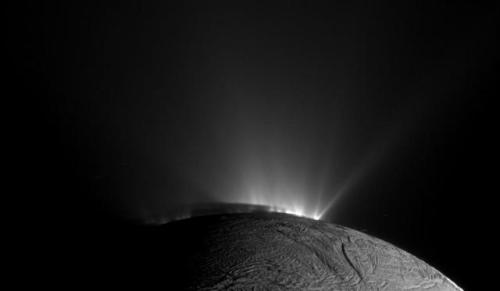

Enceladus, moon of Saturn, observed by the Voyager 2 space probe on August 26, 1981, from a distance of approximately 109,000 kilometers.

(Planetary Society)

Sequence of images of auroras seen at the south pole of Saturn. Images combine visible and ultraviolet light.

Credit: NASA, ESA, J. Clarke (Boston University, USA), and Z. Levay (STScI)

Tomorrow one of the most prolific and beloved spacecraft missions will come to an end when the Cassini spacecraft makes its final plunge into Saturn. After nearly 20 years in space and 13 years orbiting Saturn, the Cassini mission is close to running out of fuel. To prevent the craft from contaminating one of Saturn’s moons – which its mission revealed may harbor the ingredients for life – mission operators are instead sending it on a fatal dive into the gas giant.

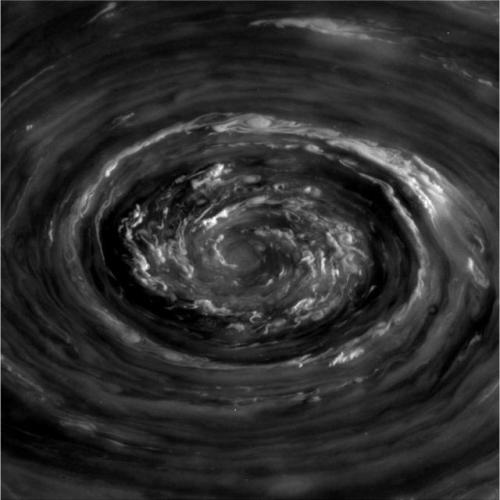

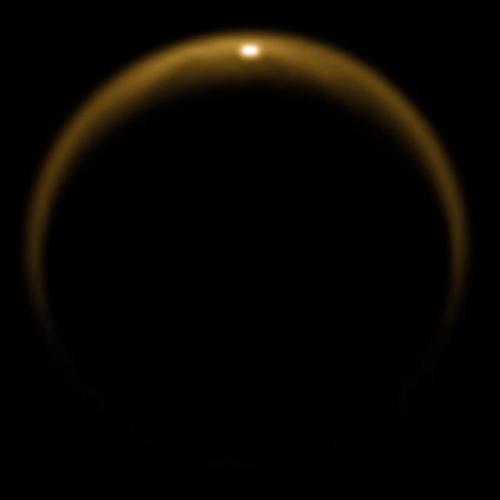

Cassini has and will continue to provide a trove of scientific insights about Saturn and its environs. It has given us front-row seats to a storm that wrapped around the entire planet. It shed new light on Saturn’s spectacular hexagonal polar vortex and showed us the beauty of auroras on other planets. Cassini also showed us that Saturn’s moon Titan has stable hydrocarbon lakes at its surface, fed by methane rains and driven by processes unfamiliar to terrestrial ones. It also gave us paths for future exploration by documenting plumes of water ejected from Enceladus’ icebound oceans.

Cassini also holds a special place in my heart. It launched while I was in middle school, reached Jupiter while I was in college, and collected data throughout my postgraduate research career. It was an inspiration for my undergraduate spacecraft mission design projects, and it provided fun and exciting fluid dynamical discoveries throughout my time writing FYFD. It’s my favorite mission (sorry, Mars rovers, New Horizons, Dawn, and Juno!) and likely to remain so for years to come.

So thank you, Cassini, and many thanks to all the scientists, engineers, and operators who’ve worked on the mission during the decades from its conception to completion. You did a hell of a job. Godspeed, Cassini! (Photo credits: NASA/JPL)

P.S. - Tonight I’ll be helping kick off the Ig Nobel Prize ceremony. You can tune into the live webcast here. The ceremony officially starts at 6 PM Eastern time, but I recommend tuning in early, especially if you want to catch my full spiel. - Nicole

Remnant of supernova toward the constellation of Vela, which exploded 11,000 years ago.

Image credit: NASA / Chandra x-ray Observatory

NGC 6960 (Western Veil nebula) & Horsehead Nebula and the Flame Nebula

by David Wills

False color image of Uranus taken with the Hale Telescope and the Palomar Observatory. The rings are the red pieces.

Image credit: Palomar Observatory & Hale telescope

-

unsuredefleur liked this · 1 month ago

unsuredefleur liked this · 1 month ago -

paradise-restored liked this · 4 months ago

paradise-restored liked this · 4 months ago -

transbordei-o liked this · 6 months ago

transbordei-o liked this · 6 months ago -

zurgy-space reblogged this · 11 months ago

zurgy-space reblogged this · 11 months ago -

zurgy liked this · 11 months ago

zurgy liked this · 11 months ago -

darkempressrising liked this · 1 year ago

darkempressrising liked this · 1 year ago -

ravexandxlust liked this · 1 year ago

ravexandxlust liked this · 1 year ago -

softedgessculptures reblogged this · 1 year ago

softedgessculptures reblogged this · 1 year ago -

softedgessculptures liked this · 1 year ago

softedgessculptures liked this · 1 year ago -

purp1e-nebula liked this · 2 years ago

purp1e-nebula liked this · 2 years ago -

clowningachievement liked this · 2 years ago

clowningachievement liked this · 2 years ago -

summonsofink reblogged this · 2 years ago

summonsofink reblogged this · 2 years ago -

susidark liked this · 2 years ago

susidark liked this · 2 years ago -

equiuszahhak reblogged this · 2 years ago

equiuszahhak reblogged this · 2 years ago -

tekras-iszovh reblogged this · 2 years ago

tekras-iszovh reblogged this · 2 years ago -

infiniteproxy reblogged this · 2 years ago

infiniteproxy reblogged this · 2 years ago -

exhausted-asterism reblogged this · 2 years ago

exhausted-asterism reblogged this · 2 years ago -

mariavasqez8 liked this · 2 years ago

mariavasqez8 liked this · 2 years ago -

agirlwithwingsnonecansee reblogged this · 2 years ago

agirlwithwingsnonecansee reblogged this · 2 years ago -

squidsandthings liked this · 2 years ago

squidsandthings liked this · 2 years ago -

sparkyairstuff liked this · 3 years ago

sparkyairstuff liked this · 3 years ago -

sophisticatedexuberance liked this · 3 years ago

sophisticatedexuberance liked this · 3 years ago -

jvcquelynn reblogged this · 3 years ago

jvcquelynn reblogged this · 3 years ago -

jvcquelynn liked this · 3 years ago

jvcquelynn liked this · 3 years ago -

bashirs reblogged this · 3 years ago

bashirs reblogged this · 3 years ago -

bashirs liked this · 3 years ago

bashirs liked this · 3 years ago -

omg-saberkitsune liked this · 3 years ago

omg-saberkitsune liked this · 3 years ago -

venus-born reblogged this · 3 years ago

venus-born reblogged this · 3 years ago -

0110100101 reblogged this · 3 years ago

0110100101 reblogged this · 3 years ago -

writing5ever liked this · 3 years ago

writing5ever liked this · 3 years ago -

the-galaxy-is-my-bxtch reblogged this · 3 years ago

the-galaxy-is-my-bxtch reblogged this · 3 years ago -

silentexplorer liked this · 3 years ago

silentexplorer liked this · 3 years ago -

blackcr0wking reblogged this · 3 years ago

blackcr0wking reblogged this · 3 years ago -

lafleur-de-mer reblogged this · 3 years ago

lafleur-de-mer reblogged this · 3 years ago -

cepn reblogged this · 3 years ago

cepn reblogged this · 3 years ago -

lasatfat reblogged this · 3 years ago

lasatfat reblogged this · 3 years ago -

its-astrotea-love liked this · 3 years ago

its-astrotea-love liked this · 3 years ago

For more content, Click Here and experience this XYHor in its entirety!Space...the Final Frontier. Let's boldly go where few have gone before with XYHor: Space: Astronomy & Spacefaring: the collection of the latest finds and science behind exploring our solar system, how we'll get there and what we need to be prepared for!

128 posts