The Editing Agenda: Those Darn Dashes

The Editing Agenda: Those Darn Dashes

When it comes to formatting and punctuation issues, hyphens and dashes take the cake. Their use in books is incredibly inconsistent, which leads to a lot of confusion for anyone trying to learn them. This article will give a thorough breakdown of each kind and their uses as they pertain to fiction. Keep in mind that the rules I’m covering are the ones that are the most beneficial for fiction writing—there are some that won’t be addressed in this post. And all rules mentioned are based on The Chicago Manual of Style, 16th Edition.

Hyphens

Phrasal Adjectives

Phrasal adjectives are a short group of words (usually two but sometimes three or more) that link together to modify another noun. They typically precede the noun and are very common in fiction writing.

Example 1: rose-colored glasses

Example 2: four-chambered heart

A fantastic resource for this can be found on The Chicago Manual of Style website: http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/16/images/ch07_tab01.pdf

This chart shows you the breakdown of various combinations of adjectives and how they should be punctuated, including permanently hyphenated words and exceptions. The CMOS advises following Merriam-Webster’s dictionary for determining which words and phrases should always be hyphenated. Some of examples of this are the words life-form, run-down (not to be confused with rundown, which holds a different meaning), and short-lived.

Compound Name

Hyphens are also used for compound names, including surnames, first names, and other names.

Example 1: Merriam-Webster

Example 2: Mary-Kay

Example 3: Theta-Gamma

Word Division

The most common word division breaks where you’d find hyphens would be line breaks, syllable breaks (often used for pronunciation purposes), and prefixes and suffixes. Which isn’t all that common in fiction writing. However, you will often see it in dialogue, particularly with stuttering.

Example: “W-w-where’d you l-l-leave it?” Tom asked.

Separators

Hyphens can also be used to separate letters and numbers. That’s that type of thing you see with phone numbers, ID numbers, and the like. However, a great use for separation hyphens in fiction writing if when have a word that you need to spell out completely or partially.

Example: The sign read: “C-A-U-T.” The rest had long worn off.

En Dashes

Dates, Times, and Page Numbers

The en dash’s main purpose is to replace the word to. The most typical occurrence of this would be with dates, times, and page numbers.

Example 1: He held office from 1929–1932.

Example 2: The event is Saturday, 2:30p.m.–4:30p.m.

Example 3: Tonight’s assignment is to read pages 32–45.

You also might see this with scoring/votes and with an unfinished number range.

Example 4: We won our last game 13–2.

Example 5: The magazine (2003–) has produced six volumes so far.

However, you should always use the word “to” instead of an en dash if “from” precedes the range.

Example 6: He joined us from 11a.m. to 12p.m. but had to leave for lunch after that.

Directions and Compound Adjectives

En dashes are also sometimes used with words, as can be the case with directions.

Example 1: I took the London–Paris train last week.

And sometimes—very rarely—an en dash is used with compound adjectives. This is where it gets tricky because the intended meaning can often get muddled by using this method, so it’s usually best to reword and find a more elegant solution when possible.

Example 2a: I’d like to find more Taylor Swift–style music.

Example 2b: I’d like to find more artists like Taylor Swift.

Version 2b of the above example flows much better and is less confusing than the first, so it’s definitely the better choice.

And with two sets of compound adjectives where the sets are acting as coordinate adjectives to each other, a comma is the best option.

Example 3: This run-down, high-maintenance property will end up costing a lot of money.

Universities

The last use of en dashes is one that you probably won’t find in most fiction writing, but it’s useful to know nonetheless. You will sometimes find universities with multiple campus locations using an en dash to include the location name.

Example: I put my application in for Fordham University–Westchester.

Em Dashes

Em dashes are used to set off phrases and clauses in a manuscript that require an abrupt break, either to draw attention to it or because there is a large shift in the train of thought. This is one of the most useful tools an author has in fiction writing when it’s used correctly and sparingly. Note that em dashes should NOT be substituted with ellipses; the two serve different purposes.

Em Dashes vs. Ellipses

Em dashes are used for interruption or to set off an explanatory element. An ellipsis is used to indicate hesitation or trailing off.

Example 1: “Lucy, where did you put—”

“It’s none of your business!” Lucy shouted from the other room.

Example 2: I stumbled down the stairs—the power had gone out earlier that evening—before I found my way to the bathroom.

Example 3: “I don’t know…” I admitted. “I hadn’t really thought much about it.”

Interrupted Thoughts

Sometimes the interruptions can come in the form of narrative thoughts.

Example: Justin’s feet pounded against the ground as he blazed down the trail. Awesome. If he kept up the pace, he’d beat—a tree root caught his foot, and he was sent sprawling into the dirt.

And if you have a character that is having trouble forming a sentence due to the circumstances at hand and/or heighted emotions, em dashes can be used to indicate stammering between words (not syllables).

Example: “What I meant was—why can’t we—oh, just forget it,” Julie spat out.

Words and Phrases

An em dash can also be used to set off noun or pronoun at the beginning of the sentence.

Example: Cowards—they were the ones who sought power.

Another common use for the em dash is before the phrases “namely,” “that is,” “for example,” and others similar to those.

Example: We spent most of the afternoon in the garden—that is, until the heat got to be unbearable.

Note: You should never use em dashes within or immediately following an element that already has a set of em dashes. Not only would this look terrible aesthetically, but it could also cause potential misinterpretation.

Interrupted Dialogue

The last use of em dashes for fiction is probably one of the trickiest, but it can also be the most useful. If you have a line of dialogue that is split up by an action in the middle, you can use em dashes to set off that action.

Example 1: “Well, the thing is”—Tommy quickly turned his attention to his feet—“it’s just not working out between us.”

Note that the em dashes go outside of the quotation marks in such a case, and the quotation is a continuous line of dialogue that is being split. The first word of the dialogue after the split should be lowercase. You can’t use this method if you have two separate sentences that have an action in between. In that situation, you’d use periods.

Example 2: “You really mean it.” I could hear my voice catch in my throat. “I just don’t understand what happened.

Two-Em Dash

One type of em dashes that is not commonly used in fiction writing that is probably my favorite is the 2-em dash. The 2-em dash is used to omit words or parts of words that are missing or illegible, or to conceal a name. Two em dashes are most useful for the genres of fantasy, thriller, and mystery, where characters might come across documents that have damage to them. The example below is from a snippet of a work in progress of mine: book one of the Ansakerr series.

My dearest I——,

If you are reading this, I have long since p—— away. I can only pray that my —— box and this letter have fallen into your hands and your hands alone. There is much you have yet learn to about me. There is still a D——k O—— out there, one more dangerous than you can imagine. For now, you are protected, but be on your toes, my girl. One day soon, I fear the p—— will fade, and you’ll need to be ready. He is coming.

The key will lead you to A——. It will hold the answers you’re looking for.

Deepest love and affection,

Grandma Bea

Notice that most of the missing parts are for key elements, including names, places, and very specific items that are clearly key for the plot. If you craft these parts well, you can purposely mislead a reader in the narrative, giving a bit of a twist to your story.

Formatting and Stylistic Use

No spaces should be used around hyphens or dashes except in the case of the 2-em dash when it is being used to completely omit a word. This is probably the most common error regarding formatting of hyphens and dashes that I come across. Though there is some debate about spacing among various sources, the CMOS is pretty clear about it. But again, as with anything else in writing, consistency is the most important.

As for formatting the different dashes, mainstream word processors include symbols for each that you can insert into your document. In fact, some of them even automatically convert two hyphens used together into an em dash. While most publishers will accept em dashes in the form of two hyphens (in fact, some even request that you submit manuscripts that way), when it comes to actual printing and online publishing of the material, you’ll want to make sure they’re replaced. Your document will look more professional when you use the correct symbol, and your readers will likely notice as well.

Tip: To quickly find and replace any stray instances of two hyphens with an em dash symbol, use your word processors Replace function.

Lastly, when it comes to use with other punctuation, a question mark or an exclamation mark can precede an em dash, but never a comma, colon, or semicolon. In other words, if you use an em dash where one of the latter punctuation marks would typically be used, the dash takes the place of the punctuation.

Example: He bent down to tie his shoe—but he stopped when he saw Alyssa approaching.

More Posts from Writersreferencez and Others

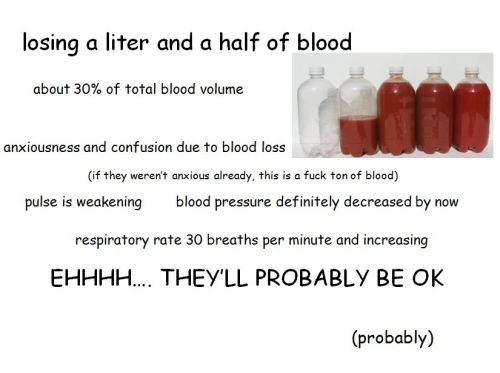

Here are some scientific facts about blood loss for all you psychopaths writers out there.

great ways to get injured solo

Sometimes another person is involved, but the truly talented whumpee can do it all on their own:

Falling out of a tree. Leads to broken bones, bruises from hitting other branches, and concussions

Food poisoning. Enough said.

Ice over a lake cracking. Full submersion leads to hypothermia. Or just a foot in the water leads to a bad case of frostbite

Animal bites. The ragged edges are hard to sew up leading to scarring. They get infected so easily, leading to fever and a long slow recovery

Snake bites. The properties of snake venom vary depending on the snake’s usual prey and predators. This means they offer a wide variety of symptoms to whump your characters with

Spider bites. See above.

Car accident. So many options. Bruising, internal bleeding, broken bones, bloody nose, whiplash, trauma, etc.

Being thrown from a horse. The old-school version of a car accident

random medical facts to use for your hospital whump writing. let your whumpee be a patient today!

if a patient has a seizure that lasts longer than 5 minutes, or if they suffer several seizures, they risk sustaining brain damage — because their brain can’t get oxygen during the seizure.

if a patient’s coughing up blood when they’re lying on their back, make sure to tune their face to the side so that they don’t choke on their own blood (the same applies to vomit too)

chest compression can and often leave patients with broken ribs. because you have to push down hard enough in order to help pump blood from the patient’s heart to their brain (the point is so that the brain gets blood, in order to prevent brain damage), and more often than not, you’ll end up breaking your patient’s ribs — that is normal and okay, because it’s better for your patient to have broken ribs than it is for them to lose their life.

after a course of electroconvulsive therapy, you’ll normally have to give your patient a dose of muscle relaxant, otherwise the aftermath of the shock may cause musculoskeletal complications.

you don't use a defibrillator to shock a patient if they already flat line, because their heart no longer has any electricity. quote "asystole isn't a shockable rhyme, and defibrillator may actually make it harder to restart the heart." (Cleveland Clinic)

the famous, classic "a character was knocked out and they stayed unconscious for hours before they woke up on their own with no lingering damage" trope is actually almost impossible if you want your work to be medically accurate (but if you don’t care about accuracy and are just here for the whump, that is totally fine!). if someone was knocked out and they stayed unconscious for more than several minutes, chances are that they suffer permanent brain damage, so they won't "wake up on their own in the next hour or two and be completely fine without intense medical attention".

Showing 'Fear' in Writing

Eyes wide with pupils dilated.

Hands trembling uncontrollably.

Heart pounding audibly in the chest.

Backing away slowly, seeking escape.

Holding breath or breathing shallowly.

Breaking out in a cold sweat.

Startling at the slightest sound.

Whispering or speaking in a hushed tone.

Looking over their shoulder repeatedly.

Clutching at clothing or objects for reassurance.

Voice quivering or stammering.

Legs feeling weak or buckling.

Feeling a chill run down the spine.

Hugging oneself protectively.

Trying to make themselves smaller.

Furtive glances around the room.

Feeling light-headed or dizzy.

Stiffening up and freezing in place.

Swallowing hard, throat dry.

Eyes darting around, unable to focus.

Emotionally reserved characters

Instead of openly sharing their emotions with others, they keep their feelings locked inside, letting their inner thoughts do all the talking. You get a glimpse into their mind, where a storm of conflicts, doubts, and desires brews quietly beneath a calm exterior. This internal monologue allows readers to understand what’s going on inside their head, even if they don’t show it on the outside. It’s like seeing the world through their eyes, where every little thing stirs up a wave of emotions that they never express out loud.

For these characters, actions speak louder than words, but even their actions are restrained. They communicate their emotions through the smallest of gestures—a slight tightening of the jaw when they’re angry or hurt, a brief flicker in their eyes when they’re surprised, or a controlled change in posture when something makes them uncomfortable. These tiny, almost imperceptible movements can say so much more than an outburst ever could, hinting at feelings they would never openly share. It’s about what they don’t do as much as what they do.

When they do speak, every word is carefully chosen. Emotionally reserved characters don’t ramble or spill their feelings in a flood of words. Instead, they speak in a measured and controlled manner, always keeping their emotions in check. Their sentences are concise, sometimes even vague or indirect, leaving others guessing about what they’re really thinking. It’s not that they don’t feel deeply, they just prefer to keep those feelings close to the chest, hidden behind a mask of calm and composure.

For these characters, what they do is often more telling than what they say. They might not say “I care about you” outright, but you’ll see it in the way they go out of their way to help, the quiet ways they show up for the people they love. Their actions reveal their emotions—whether it’s a protective gesture, a silent sacrifice, or a kind deed done without expectation of recognition. It’s these unspoken acts of kindness that show their true feelings, even if they never say them out loud.

They often have strong personal boundaries. They keep their private lives just that - private. They don’t open up easily and are cautious about who they let into their inner circle. They might deflect conversations away from themselves or avoid sharing personal details altogether. It’s not that they don’t want to connect, it’s just that they find it hard to lower their walls and let others in, fearing vulnerability or judgment.

When they do show vulnerability, it’s in small, controlled doses. These characters may have moments where they let their guard down, but only in private or with someone they deeply trust.

Sometimes, emotionally reserved characters express their feelings through objects that hold special significance to them. Maybe it’s a worn-out book they keep close, a piece of jewelry they never take off, or an old letter tucked away in a drawer. These symbolic objects are like anchors, holding memories and emotions they can’t express in words. They serve as tangible reminders of their inner world, representing feelings they keep buried deep inside.

When these characters communicate, there’s often more to their words than meets the eye. They speak in subtext, using irony, implication, or ambiguity to convey what they really mean without saying it outright. Their conversations are filled with hidden meanings and unspoken truths, creating layers of depth in their interactions with others. You have to read between the lines to understand what they’re really saying because what they leave unsaid is just as important as what they do say.

Despite their calm demeanor, there are certain things that can break through their emotional reserve. Specific triggers - like a painful memory, a deep-seated fear, or a personal loss - can elicit a strong emotional response, revealing the depth of their feelings. These moments of intensity are rare but powerful, showing that even the most reserved characters have a breaking point.

Over time, emotionally reserved characters can evolve, gradually revealing more about themselves as they grow and change. Maybe they start to trust more, opening up to those around them, or perhaps they experience something that challenges their emotional barriers, forcing them to confront their feelings head-on.

Showing 'Jealousy' in Writing

Eyes narrowing with a sharp, intense stare.

Clenched jaw and pursed lips.

Crossing arms defensively.

Making snide or sarcastic remarks.

Glancing repeatedly at the object of jealousy.

Trying to outdo or one-up the rival.

Faking a smile that doesn’t reach the eyes.

Speaking in a tense, clipped tone.

Avoiding eye contact with the person they’re jealous of.

Drumming fingers impatiently on a surface.

Feeling a burning sensation in the chest.

Sighing loudly or rolling their eyes.

Gritting teeth and taking deep, forced breaths.

Biting their lower lip hard.

Tapping foot incessantly.

Passive-aggressively commenting on the situation.

Mimicking or mocking the rival’s behavior.

Frequently changing the subject away from the rival.

Feeling a knot tighten in their stomach.

Casting resentful, sidelong glances.

Instead of "Looked", consider

glanced

peered

gazed

stared

watched

observed

examined

scrutinized

surveyed

glimpsed

eyed

beheld

inspected

checked

viewed

glanced at

regarded

noticed

gawked

spied

How to Use an Ellipsis Properly in Fiction

Ever wonder why some ellipses seem to have three dots and others have four? Some have spaces between each dot and some don’t? Why sometimes you capitalize after an ellipsis and other times you lowercase?

To be honest, I don’t think most of us were taught properly how to use an ellipsis. I know I wasn’t. I see a lot of writers who don’t understand all the rules of ellipses either.

Some of you may be wondering what an “ellipsis” is. It’s a fancy name for the three dots or “periods” you see in writing ( … ). The word “ellipsis” is Greek for “omission,” which is what it does. It shows that something has been omitted or left out.

Now with research papers, this might be obvious. Maybe you are quoting a source and don’t want to quote every single word of it, so you use an ellipsis to show that you left some stuff out. Like this:

Full quote:

“You know you’re in love when you can’t fall asleep because reality is finally better than your dreams.” - Dr. Suess

Quote with omission:

“You know you’re in love when … reality is finally better than your dreams.” - Dr. Suess

In fiction, we usually aren’t quoting sources. But the ellipsis works in similar ways, it conveys that something is omitted. This might be something directly omitted. Mamma Mia uses this method well:

July seventeenth, what a night. Sam rowed me over to the little island. We danced on the beach, and we kissed on the beach, and …

The ellipsis is used to imply they got intimate, but that part is “omitted.”

Other times things are omitted because they are incomplete–maybe an incomplete line of dialogue such as when a character trails off.

“I started to go to the school, but …” she trailed off.

Or an incomplete thought.

Would she actually want … ? she wondered.

Or maybe something is “omitted” for the sake of something else, like a character trying to censor or tone down his word choice.

“Sarah is really very … fanciful, isn’t she?” David said.

In pauses like this, the ellipsis may convey thinking. It’s completely fine to use them that way.

In rare occasions, an ellipsis might be used to indirectly convey the passing of time.

She ate … she drank … and she went shopping.

And you may occasionally see them used other ways stylistically, but these are the main situations.

In a sense, though, in all these examples, something is omitted, whether it’s directly, or indirectly, like an incomplete or changing thought, or actions in between.

When used smartly, ellipses can be powerful in fiction because they convey more than what is on the page, and that is vital to good storytelling.

Too often, however, newer writers just throw them in because they like the feel and sound of them or the long pause, or even in some cases … because they are lazy. Make sure if you use them, they have a point.

Now let’s get to the technicalities. Years ago, I used to be confused that sometimes ellipses seemed to be three dots and other times four, and I didn’t know when to use which. Ellipses are three dots. However, if it comes after a complete sentence, you still use a period.

I was so hungry… . chicken, cereal, tofu, pasta–all of it sounded good.

If it follows an incomplete sentence, you don’t use a period.

“You know you’re in love when … reality is finally better than your dreams.” - Dr. Suess

If the words after the ellipsis are the start of a new sentence, you capitalize them.

"They treated me like … Want to go to dinner?“ she asked suddenly.

If not, you don’t.

When it comes to spacing before and after an ellipsis, handle it how you would a regular word.

Sarah was really very[space]…[space]fanciful.

“I started to go to the school, but[space] …[no space]” she trailed off.

One exception to this is if there is a question mark following.

Would she actually want[space]…[space]? she wondered.

According to The Chicago Manual of Style, ellipses should have a space between each dot.

Would she actually want[space].[space].[space].[space]? she wondered.

However, in APA style, there are no spaces between dots.

Would she actually want … ? she wondered.

Fiction typically follows The Chicago Manual of Style, but you may still see the ellipsis with no spaces, especially since word processors sometimes reformat ellipses automatically. So while technically they should have spaces between each dot, you probably aren’t going to get reprimanded if you don’t. Even The Chicago Manual of Style notes that some places will be fine with the no-space ellipsis. I use spaces because that’s how I was corrected by a mentor once.

One more thing: Ellipses do not signify an interruption.

WRONG:

“I wish …”

“Shut up!” Mike interrupted.

Use em dashes for that.

Correct:

“I wish–”

“Shut up!” Mike interrupted.

Dashes are another subject.

But hopefully now you know how to handle ellipses!

Words instead of sighed and frowned?

Sighed - let out a deep audible breath or made a similar sound (such as weariness or relief)

Exhaled - breathed out

Heaved - uttered with obvious effort or with a deep breath

Huffed - emitted puffs (as of breath); usually with indignation or scorn

Insufflated - blew on, into, or in (something)

Puffed - blew in short gusts; exhaled forcibly

Snorted - forced air violently through the nose with a rough harsh sound (to express scorn, anger, indignation, or surprise)

Snuffled - breathed through an obstructed nose with a sniffing sound

Suspired - drew a long deep breath; sighed

Frowned - contracted the brow in displeasure or concentration

Glared - stared angrily or fiercely

Glouted - (archaic) frowned, scowled

Glowered - looked or stared with sullen annoyance or anger

Grimaced - distorted one's face in an expression usually of pain, disgust, or disapproval

Loured - looked sullen; frowned

Moue - a twisting of the facial features in disgust or disapproval

Pouted - showed displeasure by thrusting out the lips or wearing a sullen expression

Scoffed - expressed scorn, derision, or contempt

Scowled - contracted the brow in an expression of displeasure

Sulked - silently went about in a bad mood

Hope this helps. If it inspires your writing in any way, please tag me, or send me a link. I would love to read your work!

More: Word Lists ⚜ Writing Resources PDFs

-

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 1 week ago

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 1 week ago -

heckcareoxytwit liked this · 2 weeks ago

heckcareoxytwit liked this · 2 weeks ago -

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 3 months ago

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 3 months ago -

cremebrulee-69 reblogged this · 9 months ago

cremebrulee-69 reblogged this · 9 months ago -

cremebrulee-69 liked this · 9 months ago

cremebrulee-69 liked this · 9 months ago -

hattsravenandwritingdesk reblogged this · 10 months ago

hattsravenandwritingdesk reblogged this · 10 months ago -

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 10 months ago

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 10 months ago -

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 1 year ago

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 1 year ago -

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 1 year ago

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 1 year ago -

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 1 year ago

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 1 year ago -

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 1 year ago

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 1 year ago -

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 1 year ago

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 1 year ago -

write-101 reblogged this · 1 year ago

write-101 reblogged this · 1 year ago -

oligoweee reblogged this · 1 year ago

oligoweee reblogged this · 1 year ago -

audreycecilemoore reblogged this · 1 year ago

audreycecilemoore reblogged this · 1 year ago -

iwillhaveamoonbase liked this · 2 years ago

iwillhaveamoonbase liked this · 2 years ago -

mildly-upset-cat liked this · 2 years ago

mildly-upset-cat liked this · 2 years ago -

s-j-u-r-s liked this · 2 years ago

s-j-u-r-s liked this · 2 years ago -

exorcist-taylor-kaine liked this · 2 years ago

exorcist-taylor-kaine liked this · 2 years ago -

onionhighonionandrenown reblogged this · 2 years ago

onionhighonionandrenown reblogged this · 2 years ago -

onionhighonionandrenown liked this · 2 years ago

onionhighonionandrenown liked this · 2 years ago -

swimmingcomicbookscomicsflap liked this · 2 years ago

swimmingcomicbookscomicsflap liked this · 2 years ago -

oxymitch-archive reblogged this · 2 years ago

oxymitch-archive reblogged this · 2 years ago -

oxymitch-archive liked this · 2 years ago

oxymitch-archive liked this · 2 years ago -

tritagonists liked this · 2 years ago

tritagonists liked this · 2 years ago -

ofinkblotsandscript reblogged this · 3 years ago

ofinkblotsandscript reblogged this · 3 years ago -

mr-cactisold liked this · 3 years ago

mr-cactisold liked this · 3 years ago -

wiskeyindrometano15 liked this · 3 years ago

wiskeyindrometano15 liked this · 3 years ago -

nomore-peep reblogged this · 3 years ago

nomore-peep reblogged this · 3 years ago -

worldevastator reblogged this · 3 years ago

worldevastator reblogged this · 3 years ago -

ilightmytorch reblogged this · 3 years ago

ilightmytorch reblogged this · 3 years ago -

sovvannight liked this · 3 years ago

sovvannight liked this · 3 years ago -

anartcalledwriting reblogged this · 4 years ago

anartcalledwriting reblogged this · 4 years ago -

worldevastator liked this · 4 years ago

worldevastator liked this · 4 years ago -

strangelyxnormal-a reblogged this · 4 years ago

strangelyxnormal-a reblogged this · 4 years ago -

writingandtherapy reblogged this · 4 years ago

writingandtherapy reblogged this · 4 years ago -

jupitersref reblogged this · 4 years ago

jupitersref reblogged this · 4 years ago -

artist-in-space liked this · 4 years ago

artist-in-space liked this · 4 years ago -

scribblerinprogress reblogged this · 4 years ago

scribblerinprogress reblogged this · 4 years ago -

jestxering-a2 liked this · 4 years ago

jestxering-a2 liked this · 4 years ago