Using The Appropriate Vocabulary In Your Novel

Using the appropriate vocabulary in your novel

It is very important that the language in your novel reflects the time and place in which the story is set.

For example, my story is set in Italy. My characters would never “ride shotgun”, a term coined in US in the early 1900s referring to riding alongside the driver with a shotgun to gun bandits.

Do your research! A free tool that I found to be very useful is Ngram Viewer.

You can type any word and see when it started appearing in books. For example…one of my characters was going to say “gazillion” (I write YA) in 1994. Was “gazillion” used back then?

And the answer is…YES! It started trending in 1988 and was quite popular in 1994.

Enjoy ^_^

More Posts from Thequeerish and Others

I’m going to try this!

how to make a story file

As I am preparing for Camp NaNo*, I have been working on my story file. It occurred to me this might not be common or popular practice. “Story File” is a name I gave it and maybe some of y’all have a different name with the same contents.

*There’s still time to apply to join my Camp NaNo cabin!

My Story File contains everything about my story that doesn’t go in the outline.

It’s broken up into major categories and specific templates. So without further ado, here is how I structure my Story File.

Intro

Title

Logline

Synopsis

Genre

Estimated Total Length (word count)

Draft Length Goal (word count)

Character Bank

Main characters and brief, one-sentence descriptions with ages

Themes and Character Development

Central Question

The Yes/No question that is being asked through the whole story

Should have objective qualities, rather than subjective

i.e. “Will they fall in love?” (subjective) vs. “Will they leave their partners and become a couple?” (objective)

Thematic Questions

These are the internal conflict questions that reside in your character(s) and your story

ex. “Can there really be a successful government?”

ex. “Does grief excuse bad actions?”

Themes at a Glance

Words or phrases that relate to the themes of the story

ex. person vs. nature

ex. isolation

ex. grief

ex. first love

Motivation / Stasis State / Final State

for each main character, you should write a sentence or two pertaining to these three things

Motivation: What is the drive behind this character and their past, present, and future actions? What part of their background makes them the way that they are? What are they looking for? What do they want out of this/a situation?

Stasis State: What are they like before the inciting incident? What problems and questions do they have?

Final State: What has changed about them and their outlook? What questions have they resolved? What has happened to their internal conflict?

Relationships

I usually make a little web of the MCs and their relationship to one another. One for the stasis and one for final.

Stasis: How do these characters see each other? How do they act toward the other? (All before the inciting incident)

Final: How do these characters see each other now? How has their idea of one another shifted?

Even if a character dies before the end, include the most recent relationship status in the Final web.

ex. this is how I organize it, using the Draw feature of Google Docs

Character Bank

This is just a very preliminary character bank. If you prefer a more in-depth one, check out my 6 Box Method.

Per (relevant/important) character:

Name

Nickname/preferred name

Age

Field/Occupation

Physical Description

Personality

Personal History

Education/Occupation History

Extra Notes:

Worldbuilding Bank

(Check out my worldbuilding posts on Categories Pt. 1 and 2 for better context)

Seasons and Climate

Languages

Other Cultural Pockets

Folklore and Legends

Fine Arts

Dress and Modesty

Classes

Jobs

Currency and Economics

Shopping

Agriculture and Livestock

Imports and Exports

Literature, Pop Culture, and Entertainment

Food and Water

Holidays and Festivals

Family and Parenting

Relationships

Housing

Religion and Beliefs

Government

Health and Medicine

Technology and Communication

Death

Transportation

Plants, Animals, and Human-environment Interaction

Education

Beauty Standards

Gender and Sexuality

—————————

I hope this helps y’all and supplements what you’re probably already doing. I know it’s helped me tons to have everything in a central place.

Best of luck!

Hot take: Actual literary analysis requires at least as much skill as writing itself, with less obvious measures of whether or not you’re shit at it, and nobody is allowed to do any more god damn litcrit until they learn what the terms “show, don’t tell” and “pacing” mean.

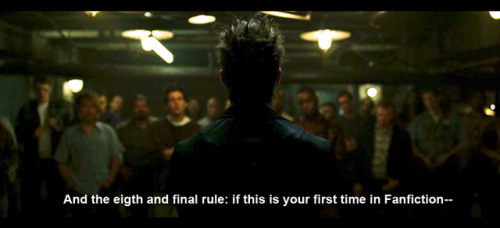

Fanfiction Club: The Rules

This idea came to me when I woke up first thing this morning.

author: sorry I’m jumping on this bandwagon and writing a fic with the same premise as all these other fics

me, has read 500 fics like this one and is prepared to read 500 more: please never apologize for giving the people (me) what they (also me) want

How to stop researching (or worldbuilding) and start writing

This is actually advice my mentoring professor gave me when I was writing my first thesis.

He said: Accept that you are never done. There is always more to know, more to research, more questions raised than answered. At some point, you just got to start writing.

Now, “easier said than done, this accepting”, I thought.

I started writing because my thesis deadline was looming. But what if you’re writing a novel and you have no deadline? How do you know when it’s okay to stop researching? When is it okay to stop worldbuilding? (Which is just like doing research, but in your own head instead of in reality.)

My advice to you is: start writing, and you’ll run into the gaps you still need to fill. Then you know what to research before starting your second draft. Let your story tell you what it needs.

For example:

Just fill your margins with a to-research-list for your future self.

That way, it’s also managable: “I finished my first draft, and I have a list of 317 things I need to decide on.” Instead of: “I saw on tumblr that you can’t build a world without knowing everything about the sewage system! And gosh, I haven’t invented three languages yet!”

Advantages:

You get things done.

It’s not overwhelming.

You don’t spend your time inventing things you’ll like so much that you want to infodump them into your story.

You mainly research things that are relevant to your story.

Well, knowing you, you already researched enough irrelevant stuff too.

You get things done.

I hope this was helpful. Don’t hesitate to ask me any questions, and happy writing!

Follow me for more writing advice, or check out my other writing advice here. New topics to write advice about are also always welcome.

Tag list below the cut, a few people I like and admire and of course, you can be too. If you like to be added to or removed from the list, let me know.

Keep reading

Hanging Hearts

Watercolor and Ink on Cotton Paper

2019, 5"x 7"

Bleeding Hearts

Writing vs Storytelling Skills: Improving Writing

Though “writing skill” is often used to refer to all aspects of story crafting, it best refers to the actual writing and technical skills that create the written word of a novel. Addressed in the previous post: Writing vs Storytelling Skills (link embedded), now I’m here to tell you how to work on that specific writing skill.

1. Study up on Literary Techniques: English class isn’t just for assigned reading and essays if you’re serious about bettering your writing. While essay writing and creative writing are different, the literary techniques and how they’re used and applied is good knowledge to have. Especially because a lot of them overlap with tropes and tie into storytelling!

2. Read a variety of books. Various authors, various genres, the more you expand your examples the better. Variation of reading means you’ll be exposed to more ideas, more ways of thought, more writing styles, more everything that you can draw ideas from and help develop your own skill. Even take up books you may not like. Give them a chance, and if the writing isn’t working for you then keep tabs on why.

3. Critique the writing of others. What did you like? What didn’t you like? How does the writing style affect how the book reads? When you critique others, you identify what makes and doesn’t make “good writing”. While a writer can only critique at a close level to their skill, the more they critique, the higher skill climbs, and the better they get. To become a better writer, you should get used to tearing other’s, and your own, work apart. It can help to keep a journal or some kind of record of critiques because as you gain more skill you may change your mind on some points.

4. Tighten up your grammar. It’s fine to make mistakes, especially in a first draft, but if you have consistent grammar errors then it’s time to tackle the issue. Grammar isn’t optional; it exists to help with clarity of communication and a clearer writer is a better writer. It’s true that creative writing allows for the use of semantic grammar or a more fluid approach to sentence structure, but there’s a difference between using purposefully altered grammar for a reason versus just not knowing how to write properly.

5. Try writing exercises. Many of these exist, from things like The Sprint (link embedded), which can help train you get work done, or The POV Swap (link embedded), which works on distinguishing character voice and perspective. Not all exercises are for everyone because there’s a variation to writing styles, but it never hurts to put in some effort to step outside our comfort zone to see if it could work. Further the benefits of writing exercises by developing a routine of regular use.

6. Read your work out loud. The mind has a tendency to put a haze of glory over some things and one way to help look at your writing realistically is to read it out loud to yourself. Reading out loud helps catch errors, some even grammatical, measure flow, evaluate pacing– it’s an amazing technique that gives the writer a better idea of what they’ve really put down. When reading, don’t be afraid to get into it and put emotion into your voice as long as it’s coming from the flow of the writing itself and isn’t forced.

All that said, there’s no such thing as a “perfect writer”. Brushing up on writing skills isn’t about being perfect, it’s about getting better relative to where you were before (and potentially helping close the gap between writing and storytelling skills).

Keep trying, keep practicing– keep writing.

Thinking of asking a question? Please read the Rules and Considerations to make sure I’m the right resource, and check the Tag List to see if your question has already been asked. Also taking donations via Venmo Username: JustAWritingAid

Day forty-six

of @the-wip-project‘s challenge.

Q46: What does your editing/revision process look like?

A46: I’ve been thinking a lot about this. My former process was not working for me as I ended up with multiple drafts of the same scene. My current approach (and subject to change) is to write out the whole story then perform a series of editing pass throughs with specific intentions, e.g., plot structure, characters behave within character, believable science, doing rather than saying/explaining, appropriate tech/ fashion/ music per era, grammar and spelling, “awesome” eradication.

-

catalllo reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

catalllo reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

silviaelric reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

silviaelric reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

newdawnhorizon reblogged this · 3 weeks ago

newdawnhorizon reblogged this · 3 weeks ago -

savingwritingthings reblogged this · 1 month ago

savingwritingthings reblogged this · 1 month ago -

shans-writings reblogged this · 1 month ago

shans-writings reblogged this · 1 month ago -

sentryofwords reblogged this · 2 months ago

sentryofwords reblogged this · 2 months ago -

writeshine reblogged this · 2 months ago

writeshine reblogged this · 2 months ago -

collectedwritingresources reblogged this · 3 months ago

collectedwritingresources reblogged this · 3 months ago -

convictshipcaptain liked this · 3 months ago

convictshipcaptain liked this · 3 months ago -

ladyofmisfortune liked this · 3 months ago

ladyofmisfortune liked this · 3 months ago -

linde121 liked this · 3 months ago

linde121 liked this · 3 months ago -

onestabbyraccoon liked this · 3 months ago

onestabbyraccoon liked this · 3 months ago -

tenderheliotrope reblogged this · 3 months ago

tenderheliotrope reblogged this · 3 months ago -

tenderheliotrope liked this · 3 months ago

tenderheliotrope liked this · 3 months ago -

southern-gothicc reblogged this · 3 months ago

southern-gothicc reblogged this · 3 months ago -

maiaofmischief reblogged this · 3 months ago

maiaofmischief reblogged this · 3 months ago -

iseiseri reblogged this · 4 months ago

iseiseri reblogged this · 4 months ago -

cure-bluepetal liked this · 4 months ago

cure-bluepetal liked this · 4 months ago -

mxballerrs liked this · 4 months ago

mxballerrs liked this · 4 months ago -

spinokitten reblogged this · 4 months ago

spinokitten reblogged this · 4 months ago -

3ambird reblogged this · 4 months ago

3ambird reblogged this · 4 months ago -

enihk liked this · 4 months ago

enihk liked this · 4 months ago -

breqvendaai liked this · 4 months ago

breqvendaai liked this · 4 months ago -

vocallife reblogged this · 4 months ago

vocallife reblogged this · 4 months ago -

ethanthealien liked this · 4 months ago

ethanthealien liked this · 4 months ago -

icereader12 reblogged this · 4 months ago

icereader12 reblogged this · 4 months ago -

icereader12 liked this · 4 months ago

icereader12 liked this · 4 months ago -

livefungus reblogged this · 4 months ago

livefungus reblogged this · 4 months ago -

giratina-and-the-skys-bouquet liked this · 4 months ago

giratina-and-the-skys-bouquet liked this · 4 months ago -

giratina-and-the-skys-bouquet reblogged this · 4 months ago

giratina-and-the-skys-bouquet reblogged this · 4 months ago -

megan-halsey liked this · 4 months ago

megan-halsey liked this · 4 months ago -

smol-awkward-potato liked this · 4 months ago

smol-awkward-potato liked this · 4 months ago -

mozarteanchaos liked this · 4 months ago

mozarteanchaos liked this · 4 months ago -

onefernecito reblogged this · 4 months ago

onefernecito reblogged this · 4 months ago -

splatoonlink liked this · 4 months ago

splatoonlink liked this · 4 months ago -

kromazque liked this · 4 months ago

kromazque liked this · 4 months ago -

shinylyni reblogged this · 4 months ago

shinylyni reblogged this · 4 months ago -

duskgryphon liked this · 4 months ago

duskgryphon liked this · 4 months ago -

avonsdrabbles reblogged this · 4 months ago

avonsdrabbles reblogged this · 4 months ago -

avonsdrabbles liked this · 4 months ago

avonsdrabbles liked this · 4 months ago -

finalexit liked this · 4 months ago

finalexit liked this · 4 months ago -

shipshaunted reblogged this · 4 months ago

shipshaunted reblogged this · 4 months ago -

shipshaunted liked this · 4 months ago

shipshaunted liked this · 4 months ago -

zaprowsdower27 liked this · 4 months ago

zaprowsdower27 liked this · 4 months ago -

valencrime reblogged this · 4 months ago

valencrime reblogged this · 4 months ago