241 posts

Latest Posts by s-afshar - Page 9

Presidente Andreotti – Ο Μεγαλύτερος Πολιτικός του Μεταπολεμικού Κόσμου: Τζούλιο Αντρεόττι

"Presidente Andreotti": Giulio Andreotti, the Greatest Statesman of Post-WWII World

ΑΝΑΔΗΜΟΣΙΕΥΣΗ ΑΠΟ ΤΟ ΣΗΜΕΡΑ ΑΝΕΝΕΡΓΟ ΜΠΛΟΓΚ “ΟΙ ΡΩΜΙΟΙ ΤΗΣ ΑΝΑΤΟΛΗΣ”

Το κείμενο του κ. Νίκου Μπαϋρακτάρη είχε αρχικά δημοσιευθεί την 29η Απριλίου 2018.

Ο κ. Μπαϋρακτάρης παρουσιάζει μέρος της συζήτησης και του διαλόγου τον οποίο διεξήγαγα με το ακροατήριο μιας διάλεξής μου στο Πεκίνο τον Ιανουάριο του 2018 αναφορικά με το ποιος είναι ένας πραγματικά ισχυρός ηγεμόνας (ή 'πολιτικός' - !!) και σχετικά με τα καίρια κριτήρια τα οποία καθορίζουν την πραγματική ισχύ ενός ανθρώπου γενικώτερα. Αυτά δεν έχουν τίποτα το κοινό με φυσική/σωματική ισχύ, οικονομική υποστήριξη, πολιτική-κομματική διασύνδεση, ή την όποια μορφωτική ('επιστημονική') γνώση (δηλαδή: αποβλάκωση). Η πραγματική ισχύς δεν φαίνεται: δεν είναι υλική, αλλά εξολοκλήρου ψυχική. Και είναι για απειροελάχιστους, οι οποίοι δεν έχουν κανένα ενδιαφέρον να επιδείξουν την ισχύ τους σε άλλους. Η αληθινή Ιστορία, δηλαδή το Γίγνεσθαι, είναι μυστικό.

--------------------------

https://greeksoftheorient.wordpress.com/2018/04/29/presidente-andreotti-ο-μεγαλύτερος-πολιτικός-του-μετα/ =============================

Οι Ρωμιοί της Ανατολής – Greeks of the Orient

Ρωμιοσύνη, Ρωμανία, Ανατολική Ρωμαϊκή Αυτοκρατορία

Σε προηγούμενο κείμενό μου σχετικά με τον Ντόναλντ Τραμπ, αναφέρθηκα στον Τζούλιο (Ιούλιο) Αντρεόττι, μυθική μορφή της μεταπολεμικής Ιταλίας και της διεθνούς πολιτικής. Πιο συγκεκριμένα, ολοκλήρωσα το κείμενό μου εκείνο με την εξής παράγραφο:

Όμως, εφόσον κάνουμε τόσες συγκρίσεις, δεν νομίζω ότι ο Τραμπ έχει την ικανότητα να περνάει με τόση ευκολία καθημερινά ανάμεσα σε τόσες πολλές σφαίρες που σφυρίζουν και για έξι δεκαετίες, όπως ένας Τζούλιο Αντρεόττι.

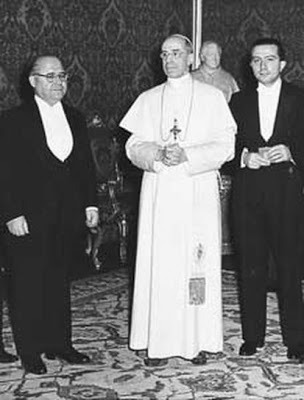

Με τον Πάπα Πίο ΙΒ’ (Εουτζένιο Πατσέλι) το 1953

Με την ευκαιρία της συμπλήρωσης πέντε ετών από τον θάνατο του βετεράνου της παγκόσμιας εξουσίας (6 Μαΐου 2013 σε ηλικία 94 ετών), αφιερώνω ένα σύντομο κείμενο με ασυνήθιστες αναφορές που δεν βρίσκονται εύκολα στα ΜΜΕ στον ‘Βεελζεβούλ’ ή στον ‘θεϊκό Ιούλιο’ – όπως τον δει κάποιος!

Giulio Andreotti, il Divo – Τζούλιο Αντρεόττι, ο Θεϊκός

Επονομασμένος και … Βεελζεβούλ!

45 χρόνια βουλευτής (υπουργός και πρωθυπουργός) και στη συνέχεια 22 χρόνια ισόβιος γερουσιαστής (ως τιμητική διάκριση): 67 χρόνια σε έδρανα δημόσιου βίου!

Il potere logora chi non ce l’ha – Η εξουσία φθείρει εκείνον που δεν την έχει

Ο μεγαλύτερος πολιτικός δεν είναι ο πλουσιώτερος από τους πολιτικούς, ή ο ισχυρώτερος, ή εκείνος που τον φοβούνται πιο πολύ, ή εκείνος που κάνει τα πιο εντυπωσιακά κι απρόσμενα πράγματα, γιατί όλα αυτά οφείλονται στην πραγματικότητα σε επιτελεία και σε παρασκηνιακές οργανώσεις που κινούν ως μαριονέτες εκείνους που ο μέσος ηλίθιος άνθρωπος θεωρεί ‘πανίσχυρους’.

Βεελζεβούλ και Βηλφεγώρ

Ο Τζούλιο Αντρεόττι, κορυφαίο στέλεχος των Ιησουϊτών, με τον μεγάλο του αντίπαλο, τον Λίτσιο Τζέλι, σεβάσμιο της μασωνικής στοάς Ρ2 και οργανωτή μιας πλειάδας αποπειρών δολοφονίας του Ιταλού πολιτικού.

Τους ονόμαζαν Βεελζεβούλ και Βηλφεγώρ.

Ο Λίτσιο Τζέλι (γεννημένος την ίδια χρονιά με τον Αντρεόττι, πέθανε δυο χρόνια μετά από κείνον / 1919-2015) είχε την ψυχική ισχύ να περάσει μέσα από τα τείχη των φυλακών, όπου τον είχαν κλείσει, αόρατος, και να μετατοπιστεί ακαριαία σε τεράστια απόσταση γελοιοποιώντας όσους κρύβοντας τη δική τους δύναμη ήθελαν να κάνουν εκείνον να δείξει τη δική του.

Ασχολούμενοι με τους δύο κορυφαίους της παγκόσμιας εξουσίας αφήνουμε τα ανθρώπινα και προσεγγίζουμε τα θεϊκά, υπερβατικά-ψυχικά επίπεδα ύπαρξης για τα οποία οι ψευτοθρησκείες των δήθεν πιστών είναι τιποτένιες αφηγήσεις κι αισχρή υποκρισία ξωφλημένη και προκαταδικασμένη να εξαφανιστεί στα επόμενα 10-20 χρόνια.

Και μαζί της κι όλη η σαββούρα των σημερινών ψευτοθρησκειών….

Κάνω λόγο για ‘θεϊκά επίπεδα ύπαρξης’.

Σωστά.

Ή σατανικά…….

Ο μεγαλύτερος πολιτικός δεν ο πιο μορφωμένος, ο πιο φιλοσοφημένος, ή ο πιο ιδεολόγος, επειδή οι υλι(στι)κές επιστήμες είναι μια παραχάραξη της αλήθειας, η φιλοσοφία αποτελεί από μόνη της αποδοχή προσωπικής έλλειψης της Σοφίας, οι ιδεολογίες και θεωρίες είναι ένα σκουπιδαριό και μια πολύ χαμηλή τακτική αποβλάκωσης των μαζών, κι η όποια ”μόρφωση είναι απλά συσσώρευση αχρήστων βλακειών που έχουν συγγράψει άνθρωποι τιποτένιοι, ανίσχυροι κι ολότελα ξεκομμένοι από την ψυχή τους – αντίθετα από το τι συνέβαινε στον Τζούλιο Αντρεόττι και στον Λίτσιο Τζέλι.

Ο μεγαλύτερος πολιτικός ή ηγέτης ή ηγεμών είναι εκείνος που δεν φοβάται να περάσει ανάμεσα σε σφαίρες που σφυρίζουν, γιατί γνωρίζει ότι έχει την ψυχική παντοδυναμία (ή αν θέλετε τα σωστά συντεταγμένα ηλεκτρομαγνητικά ρευστά του σώματός του) να τις εξοστρακίζει.

Κι ο Τζούλιο Αντρεόττι έκανε αυτό καθημερινά και για πολλές δεκαετίες.

Καμμιά από τις αναρίθμητες κι αποτυχημένες απόπειρες δολοφονίας του δεν αναφέρθηκε δημόσια.

Όποιος έχει την δύναμη δεν την δείχνει.

Γι’ αυτό κι αποκλήθηκε ο Αντρεόττι indecifrabile – μη αποκρυπτογραφήσιμος.

Non ho un temperamento avventuroso e giudico pericolose le improvvisazioni emotive. […] Lavorare molto m’è sempre piaciuto. È una… utile deformazione. Presidente Andreotti

Τζούλιο Αντρεόττι χορεύει δημοτικούς χορούς από την επίσκεψή του στα Γιάννινα στα τέλη του 1980.

Σε μοναστήρι του νομού Ιωαννίνων

Mi faccio una colpa di provare simpatia per Andreotti. È il più spiritoso di tutti. Mi diverte il suo cinismo, che è un cinismo vero, una particolare filosofia con la quale è nato. Montanelli

è distaccato, freddo, guardingo, ha sangue di ghiaccio. […] È autenticamente colto, cioè di quelli che non credono che la cultura sia cominciata con la sociologia e finisca lì. Montanelli

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giulio_Andreotti

-------------------------

più realista di Bismarck, più tempista di Talleyrand […] La sua smagliante conversazione sarebbe piaciuta a Voltaire, i suoi libri non sarebbero dispiaciuti a Sainte-Beuve. Roberto Gervaso

--------------------------

A joke about Andreotti (originally seen in a strip by Stefano Disegni and Massimo Caviglia) had him receiving a phone call from a fellow party member, who pleaded with him to attend judge Giovanni Falcone’s funeral. His friend supposedly begged, “The State must give an answer to the Mafia, and you are one of the top authorities in it!” To which a puzzled Andreotti asked, “Which one do you mean?”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giulio_Andreotti

Στη Μόσχα το 1973

Στην Παλμύρα της Συρίας το 1989

--------------------------------------

Περισσότερα:

https://el.wikipedia.org/wiki/Τζούλιο_Αντρεότι

http://unmondoimpossibile.blogspot.com/2015/10/giulio-andreotti-come-fecero-fuori.html

http://giulioandreotti.org/it

-------------------------------------------

Κατεβάστε την αναδημοσίευση σε Word doc.:

https://www.slideshare.net/MuhammadShamsaddinMe/presidente-andreotti

https://issuu.com/megalommatis/docs/presidente_andreotti.docx

https://vk.com/doc429864789_621710290

https://www.docdroid.net/0ouL4w6/presidente-andreotti-o-meghalyteros-politikos-toy-metapolemikou-kosmoy-docx

Το Ιράν των Αγιατολάχ: ένα Μασωνικό Παρασκεύασμα - αποκαλύπτει ο Έλληνας Ιρανολόγος καθ. Μουχάμαντ Σαμσαντίν Μεγαλομμάτης

Ayatollahs' Iran: A Freemasonic Fabrication, reveals the Greek Iranologist Prof. Mohammad Samsaddin Megalommatis

ΑΝΑΔΗΜΟΣΙΕΥΣΗ ΑΠΟ ΤΟ ΣΗΜΕΡΑ ΑΝΕΝΕΡΓΟ ΜΠΛΟΓΚ “ΟΙ ΡΩΜΙΟΙ ΤΗΣ ΑΝΑΤΟΛΗΣ”

Το κείμενο του κ. Νίκου Μπαϋρακτάρη είχε αρχικά δημοσιευθεί την 27η Σεπτεμβρίου 2018.

----------------------------

https://greeksoftheorient.wordpress.com/2018/09/27/το-ιράν-των-αγιατολάχ-ένα-μασωνικό-παρ/ =============================

Οι Ρωμιοί της Ανατολής – Greeks of the Orient

Ρωμιοσύνη, Ρωμανία, Ανατολική Ρωμαϊκή Αυτοκρατορία

Αναδημοσιεύω εδώ ένα εντυπωσιακό άρθρο του Έλληνα ανατολιστή ιστορικού και πολιτικού επιστήμονα, καθ. Μουχάμαντ Σαμσαντίν Μεγαλομμάτη, ο οποίος διαλύει πολλούς μύθους που υπάρχουν στην κοινή γνώμη σχετικά με το Ιράν ως τάχα ‘αντίπαλο’ της δυτικής Νέας Τάξης Πραγμάτων.

Αρχικά δημοσιευμένο το 2007, το ανατρεπτικό άρθρο αναδημοσιεύθηκε σε πολλά ιρανικά πόρταλς της Διασποράς επειδή οι Ιρανοί κατάλαβαν εύκολα το τι έλεγε για την χώρα τους ο εξαίρετος Έλληνας ιρανολόγος, ο οποίος έχει μελετήσει την ιστορία του Ιράν και έχει περιπλανηθεί στην χώρα εκείνη όσο ελάχιστοι άλλοι ειδικοί.

Ayatollahs’ Iran: a Nationalistic Theocracy as Freemasonic Machination

By M. Shamsaddin Megalommatis

Saturday 22 December 2007

http://www.fravahr.org/spip.php?article411

and https://www.academia.edu/24267250/Ayatollahs_Iran_a_Nationalistic_Theocracy_as_Freemasonic_Machination

======================

The current theocratic and utterly unrepresentative regime of Iran was not the choice of the peoples and nations of Iran. The events that triggered the fall of Shah and the return of Ayatollah Khomeini were all machinated by an Apostate Freemasonic Lodge that controls part of the French and the English establishments and through them part of the American establishment.

The danger that the late Shah of Iran represented for their eschatological plans was absolutely tremendous. This does not imply that they intended to help establish a pseudo-Shia theocracy in Iran; simply they were not able to completely control the developments. As a matter of fact, the late Shah intended to modernize, industrialize and westernize Iran in the 70s; one could compare his attempt to that of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk in Turkey, 50 years earlier.

A strong Iran next to a strong Turkey is enough to make the Anglo-French colonial establishments spend years without an easy sleep. Although this would look good for Western geo-political and geo-strategic interests, particularly in containing Tsarist Russia / USSR / Putin’s oligarchy, in real terms of Western Freemasonic conspiracy in the Middle East it is abominable because it would hinder all Freemasonic plans and projects for the Middle East, the area of their primary concern par excellence.

Mossadegh received by Truman

Mossadegh was a Freemason Islamist. His supporters became later the supporters of Khomeyni and founders of the Islamic regime.

It sounds awkward but it is absolutely real: the late Shah of Iran tried with a delay of 17 years (as of 1970) to implement the basic concepts of the Iranian nationalistic policies of Dr. Mohammed Mossadegh, a great Iranian statesman whom the Freemasonic mass media of the West did their ingenious best to defame and ridicule, while falsely portraying him as … related to the Iranian Communist party!

[In fact, Mohamad Mossadegh was himself a Freemason and an Islamist. His so-called nationalism was no more than an International-Islamism inspired by Freemasonry — Fravahr]

When Madeleine Albright, decades later, admitted that the Eisenhower administration was involved in the Operation Ajax that ended with the Mossadegh’s removal, she did not state any other reason except geopolitical considerations. In fact, these considerations were Freemasonic eschatological approaches to the Middle East, covered by English economic interests, and involved volumes of falsified information produced in order to mislead the gullible and deeply unaware American establishment — through use of pro-English agents who were active in Washington D.C.

The Shah himself must have felt in the early and mid 70s how right Mohammed Mossadegh was. In his last days in Tehran, the Shah must have also remembered his father’s last days in the throne, when in September 1941 the English had forced him to abdicate in favour of his young son, as they could not accept Iran’s neutrality in WW II.

The Freemasonic anti-Iranian conspiracy played on the Iranian peoples’ feelings against the Shah, and involved the return of Ayatollah Khomeini who had spent some months in France. In fact, the Apostate Freemasonic Lodge pushed to the political forefront Iranians who had already lived and studied in France where they had become Freemasons, like Mehdi Bazargan, Khomeini’s first Prime Minister, and Abolhassan Banisadr, the first Iranian President.

They were joined in their effort to canalize the Iranian Revolution by Sadegh Ghotbzadeh, who had studied in America, and had travelled with Ayatollah Khomeini from Paris to Tehran on February 1st 1979 to become later Foreign Minister (after Banisadr) and then be arrested and executed (September 1982) as betrayed by President George H. W. Bush. After 1983, Freemasonic influence on Iranian policies has been indirect.

Indirect manipulation involves the mental, spiritual, philosophical, ideological, and therefore political engulfment of the targeted establishment into erroneous perception of the present realities and the future targets of the Apostate Freemasonic Lodge within a context that can be rather parallelized with an iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma.

Shia Eschatology in contrast with Freemasonic Messianism

Worship of Isis

Freemasonic ritual as on the walls of the Isiac Freemasonic Lodge (Temple of Isis) at Pompeii

The worship of Isis is depicted in this wall-painting from Herculaneum. The high priest stands at the entrance to the temple and looks down on the ceremony beneath him, which is supervised by priests with shaven heads. In the case of the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the Freemasonic establishment’s arsenal reaches its limits. Drawing from a late Sassanid Zervanism that survived within Shia Islam since the early days of the Islamic conquest of Iran (636: Sassanid defeat at Qadisiyah, 641 Sassanid defeat at Nihavent, 651: arrival of Islamic armies at Merv in Central Asia), Shia Eschatology revolves around the prevalence of Time as determinant element in the Mystic History of the Mankind; this is utterly alien to Western Freemasonic dogmas and doctrines that draw from Late Antiquity’s Gnosticisms, Hermetism, and Messianic Isidism.

With Khomeini’s doctrine based on the termination of the Ghaybah (“Occultation”) of the Shia Islamic Twelfth Imam (the Shia version of the Messiah) by means of the Islamic Republic of Iran, we reach one step closer to what is called in Islam Al Yom al Ahar (“the End of Time”).

Despite the fact that Iran and most of the Islamic World are engulfed in ignorance and confusion due to the academic systems that Freemasonic Europe produced to facilitate the advent of the Freemasonic Messianic, namely the Hellenism, the Orientalism, the Pan-Arabism, and the (Sunni) Islamism, the Shia establishment of Iran, sticking to the completion of the work initiated by Ayatollah Khomeini, have little chance to be misguided and deceived.

Contrarily to the Freemasonic concept of a Horus — Messiah, creation of Isis (as Freemasonry is symbolized within the Freemasonic eschatological doctrine), a Zervan — Twelfth Imam hinges on the absorption of all into a New Aeon with little concern about an Elected People to be saved.

Contrarily to a Horus — Victorious King and Pacifier, the concept of Zervan — Twelfth Imam involves the liberation of every person from the negative energy therein encrusted through various ways; as Zervan Akarana promises a monstrous appearance, yet able to embody the Loftiest of the Divine, the Shia Islamic Twelfth Imam promises no peace and no return for any elected people, but heralds the miraculous transformation of the miserable into luminous sources in the present world (after Al Yom al Ahar) and the Hereafter (Al Yom al Qiyamah).

There is certainly a Manichaean influence on the late Sassanid Zervanism (and through this system on the Shia Islam) but the Western stern rejection of Manichaeism proliferated only confusion and dire practices among the Apostate Freemasons. In fact, the Freemasonic Apostasy is a repetition of an earlier Apostasy that took place in the Late Antiquity, and caused the disastrous descent into the Middle Ages.

Unable to transcend, the Apostate Freemasonic Lodge seems set for disastrous developments that will now cover the entire surface of the Earth. Determined to continue an evil process started by Napoleon and sped up by Edmund Allenby, the Apostate Freemasonic Lodge seems today unable to perceive the impending domino effect that will ensue from an attack on Iran. The Apostate Lodge machinated the Anglo-French colonialism in order to create a false and precarious Israel (for Jews, not Israelites), thus exterminate both Jews and Palestinians (after a supposed final peace), and then set up a true Israel able to accommodate the migrating — because of expected ominous natural phenomena — English, Irish, Scots, French, Belgian, Dutch, and Scandinavians (namely the true descendants of the Ten Tribes of Israel). That final Israel that would span between the rivers Euphrates (Assyria) and Nile (Egypt) may simply never come to existence because of the rise of a New Era for the Middle East triggered by an attack on Iran.

The Advent of the End of Time

If Ahmadinejad referred to Mahdi’s advent (which means automatically the End of Time) already in his first speech at the UN (in September 2005), what happened meanwhile that indicates that by now an apocalyptic scenario would follow an American attack on Iran? Why what could happen in March 2006 should not occur in December 2007?

The answer to such a question is at the same time a full response to a great number of eschatological interpretations. The History of the Mankind can also be viewed as a History of missed opportunities. More recently, after 2001, to give an example, the US could have pacified Iraq, if they had the knowledge and the courage to do what it would take. Simply, they were either unaware or misled. Usually, to know how a solution can be found to a historical — political problem, one has to transcend; this mainly means that one has to see the problem in question as a non-problem, or place it within wider frame, or view it through different standpoints, or apply all these methods. Basically, a historical — political problem’s solution involves the non-consideration of a part’s interests.

An answer to the aforementioned question is at the same time a complete rejection of numerous approaches to historical texts of eschatological contents. As a matter of fact, there has always been a vast interpretational literature of the Prophetic books of the Bible, of the Revelation, of the Apocalyptic Hadith, and of the eschatological traditions of various peoples from India to Mexico. With the inception of the web, and the rise of spiritual interest in a post-Communist world, the interpretational interest only multiplied. Specifications and clarifications about the time of the arrival of Mahdi, the Messiah, Jesus as Islamic Prophet, Jesus as Christ of the Christian religion, etc. can be found in great number.

All these approaches emanate from a world plunged into the swamp of Time, a world whereby all people take for granted that Time exists. Yet, the Mankind existed for several thousands of years without shaping the concept of Time. For many great thinkers and wise elders in Sumer, Akkad, Egypt, Assyria and Babylon, Hittite Anatolia, and Biblical Israel, Time simply did not exist. The interaction of Being and Becoming was perceived completely differently, particularly by peoples who used the same word for “day” and “time” (e.g. umu in Assyrian — Babylonian). In a world viewed, perceived, sensed, and experienced diachronically, there is little place for fanaticism and empathy, as all reflect an eternal recapitulation of everything.

In that world, great diachronic (and therefore apocalyptic and eschatological) Epics were compiled for a first and original occasion, and their elements, data, concepts and details were later diffused among later epics, mythical texts and apocalyptic literature. As a matter of fact, there is nothing original that was not already said before Moses. To give an example, it is sheer ignorance for anyone to believe that the concept of the Antichrist goes as back as the Revelation and Daniel.

More than 1500 years before the Revelation, for the Anatolian Hittites the Antichrist (Ullikummi) would rise from the Sea. The author of the Revelation reassessed the same topic, adding only an effort of identification of the Messiah (Tasmisu for the Ancient Hittites — Jesus as Christ for the Christians). More than 2000 years before Isaiah, the concept of the Messiah existed in the Egyptian Heliopolitan Doctrine.

Viewing the present world through the eyes of an Egyptian, Assyrian or Hittite erudite scholar would offer a completely different perspective, and certainly more authoritative as emanating from a diachronic consideration of the Mankind’s and the World’s existence. In most of the cases, this was avoided because of the salacity of Western Orientalists, who instead of serving truth, did promote preconceived ideas either of Freemasonic or Christian Catholic nature. What would destroy pillars of their false faiths had to be covered by silence; this is the “veracity” of the Western universities’ professors.

2007: A Changed World and Iran

In fact, many things have changed over the past 21 months; they are not easily visible to average people and supposed leaders. Even worse, it seems that they are not ostensible to panicked establishments and elites either.

Losing a unique opportunity to be the sole superpower and thus accomplish the wishes of the Founding Fathers, the US will have to become familiar with the reality of a multi-polar world.

If we exclude the nonsensical nuclear mutual destruction, which will be always a possibility, as long as nuclear weapons exist, America’s interests can be hit at any moment. America lost considerably because America allied itself with the only country they should never work together: England.

Discrediting America, exposing the US, while mobilizing others’ forces to contain America and finally avert a long perspective Pax Americana, England convinced the US leadership to pursue the only way that can truly damage the US interests: action against the Moral Principles that the Founding Fathers stipulated so clearly for the then young and promising, Anti-Colonial, nation that would diffuse Freedom, Justice and Democracy to the rest of the world.

The US leadership failed to assess that it would be detrimental to pursue after 1991 immoral practices employed at the times of the Cold War. The policy of double standards (two measures and two weights) would convince all possible adversaries that the US represents a threat, and would mobilize many against America. The enumeration could be very long.

Vice-president Cheney’s trip to Saudi Arabia in November 2006 was certainly taken very seriously by the Iranians — within eschatological context, I mean. The Islamic Messiah will certainly exterminate a cursed, Satanic regime in charge of Haramayn, the two holy cities of Mekka and Madinah.

One would not ask America to believe the Islamic eschatological literature; but one would anticipate America to take it into account, and shape its policy accordingly. The rest is just inane.

Saudi Arabia cannot exist — if Israel is to survive!

It was a pathetic American effort to continue English Colonial policies of division and strife in the Middle East; these policies targeting the existence of the Ottoman Empire and Imperial Iran, if pursued by America, against Turkey and Iran, can guarantee the total disaster of America.

Yet, Prof. Huntington, in a moment of truth, exposed the truth plainly, when he attributed the Islamic Extremism and Terrorism to the lack of a core State for the Muslim world. This was precisely the work of the Anglo-French Apostate Freemasonic Lodge that we already mentioned. America should not be confused with the Anglo-French secondary conflicts, as highlighted by the San Remo arguments between Clemenceau and Lloyd George.

For America’s interests to prevail, for the present state of Israel to survive, for a solution of the quasi-permanent Palestinian problem to be found, America should avoid any direct interference in the affairs of the Muslim World.

Any US attack against Iran would trigger an unexpected and unsuspected reaction that would certainly have a lot to do with Islamic eschatological expectations.

The explosion would immediately bring in other, sizeable, non-Islamic countries that are ready for a severe collapse of the present global economic structures, as their economies are better suited for barter trade. These countries would not necessarily help Iran militarily; they would simply make impossible for America to sustain the cost of a conflict spanning from Yemen and Israel to Afghanistan and Pakistan, at a moment Saudi and Emirati oilfields would not be anymore functional.

America should keep itself outside the Muslim World, and following the instructions of Prof. Huntington, help (with the cooperation of Israel) the rise of a core Muslim country in the Middle East that would eradicate the nefarious colonial deeds of the Apostate Freemasonic Lodge.

This country should be a secular and humanist, democratic country that would be committed to the elimination of Pan-Arabism and Islamic Extremism. To support the rise of a vast Oriental State, America should fervently oppose France and England.

This would redraw the map of the Middle East, but ultimately save the present state Israel, offer peace to the Palestinians, and grant concord to the other Middle Eastern countries. Only a vast Oriental State would have no problem in containing Iran and outmanoeuvring the Ayatollah regime.

Otherwise the Death will hit America — in an irrevocable and precipitated way.

Europe would be affected too; and that Apostate Freemasonic Lodge would be severely persecuted in a new — unrecognizable — Europe ruled by a new Iron Man of the North.

---------------------------------

Κατεβάστε την αναδημοσίευση σε Word doc.:

https://www.slideshare.net/MuhammadShamsaddinMe/ss-250701066

https://issuu.com/megalommatis/docs/iran_of_the_ayatullahs.docx

https://vk.com/doc429864789_621631094

https://www.docdroid.net/HEpNSXC/to-iran-ton-aghiatolakh-ena-masoniko-paraskeuasma-docx

Ορομία, 45 εκ. Ορόμο κι ο Αφρικανολόγος καθ. Μ. Σ. Μεγαλομμάτης, Πρωτεργάτης του Εθνικού – Απελευθερωτικού Αγώνα του Μεγαλύτερου Υπόδουλου Έθνους στον Κόσμο

Oromia, 45 million Oromos, and the Africanologist Prof. M. S. Megalommatis, Pioneer of the National Liberation Struggle of the World's Largest Enslaved Nation

ΑΝΑΔΗΜΟΣΙΕΥΣΗ ΑΠΟ ΤΟ ΣΗΜΕΡΑ ΑΝΕΝΕΡΓΟ ΜΠΛΟΓΚ “ΟΙ ΡΩΜΙΟΙ ΤΗΣ ΑΝΑΤΟΛΗΣ”

Το κείμενο του κ. Νίκου Μπαϋρακτάρη είχε αρχικά δημοσιευθεί την 20η Αυγούστου 2019.

----------------------------

https://greeksoftheorient.wordpress.com/2019/08/20/ορομία-45-εκ-ορόμο-κι-ο-αφρικανολόγος-κα/ ====================

Οι Ρωμιοί της Ανατολής – Greeks of the Orient

Ρωμιοσύνη, Ρωμανία, Ανατολική Ρωμαϊκή Αυτοκρατορία

Περίπου 45 εκ. Ορόμο ζουν σήμερα σε όλο τον κόσμο, κυρίως στην Αβησσυνία (που ψευδώς αποκαλείται Αιθιοπία) και στην Κένυα. Η πατρίδα τους είναι η Κατεχόμενη Ορομία. Στην Αβησσυνία (που μόνον πρόσφατα, ψεύτικα και εγκληματικά αποκαλείται Αιθιοπία) υπάρχει μια μεγάλη επαρχία ονόματι Ορομία. Αλλά τα σύνορά της επαρχίας αυτής δεν αντιστοιχούν στα πραγματικά σύνορα της Κατεχόμενης Ορομία και έτσι πολλοί Ορόμο ζουν και σε άλλες επαρχίες του τυραννικού αυτού ψευτοκράτους του οποίου ο σχηματισμός οφείλεται σε πολλές γενοκτονίες διαφόρων αφρικανικών κουσιτικών και νειλοσαχαρικών εθνών κατά τον 19ο και 20ο αιώνα. Ορόμο Διασπορά υπάρχει σήμερα στις ΗΠΑ, στον Καναδά, στην Αυστραλία, στο Σουδάν, στην Αίγυπτο και σε άλλες χώρες.

Οι Ορόμο είναι ένα κουσιτικό έθνος (δηλαδή ανατολικό χαμιτικό έθνος) και οι πιο κοντινοί ‘συγγενείς’ τους είναι τα άλλα κουσιτικά έθνη της σημερινής Ανατολικής Αφρικής: οι Σομαλοί (που είναι επίσης διαιρεμένοι: στην ευρισκόμενη σε εμφύλιο από το 1991 Σομαλία, στο Ογκάντεν της Αβησσυνίας, στην Κένυα και στο Τζιμπουτί), οι Σιντάμα, οι Άφαρ, οι Κάφα και οι Καμπάτα. Τα τελευταία τέσσερα κουσιτικά έθνη είναι και αυτά υποδουλωμένα στην Αβησσυνία. Ιδιαίτερα μάλιστα οι Άφαρ είναι τριχοτομημένοι ανάμεσα στην Αβησσυνία, την Ερυθραία και το Τζιμπουτί.

Ο λόγος για τον οποίο η Σομαλία βυθίστηκε και παραμένει σε εμφύλιο προγραμματισμένα επί σχεδόν 30 χρόνια είναι ο ίδιος για τον οποίο οι Ορόμο αντιμετώπισαν την έχθρα όλων των μεγάλων αποικιοκρατικών χωρών (Αγγλία, Γαλλία, ΗΠΑ) και την άρνηση της κατευθυνόμενης από το παρασκήνιο διεθνούς κοινότητας να ανταποκριθεί στον δίκαιο εθνικό απελευθερωτικό αγώνα τους.

Ταυτόχρονα, πολλά ψέμματα διαδόθηκαν από πανεπιστήμια, εκδοτικούς οίκους, ερευνητικά κέντρα, και ΜΜΕ ώστε να μειωθούν οι αλήθειες που διέδιδαν εθνικά απελευθερωτικά κινήματα όπως το Oromo Liberation Front.

Ο λόγος για τον οποίο δεν ξέρουν για τους Ορόμο στην Ελλάδα, στην Γαλλία, την Αγγλία, την Γερμανία, την Ρωσσία, τις ΗΠΑ, την Κίνα και άλλες χώρες του κόσμου είναι ο ίδιος για τον οποίο οι περισσότεροι άνθρωποι σε όλα τα μήκη και πλάτη της γης ξέρουν μια ψευδέστατη ιστορία, έχουν στρεβλή πληροφόρηση κι έχουν λάθος εικόνα της κατά τόπους υπαρκτής κατάστασης.

Συχνά-πυκνά η παραπληροφόρηση και η αποπληροφόρηση συνοδεύονται από την παντελή αποσιώπηση.

Και στην περίπτωση των Ορόμο ό,τι επιχειρήθηκε επιμελώς να αποσιωπηθεί είναι η γενοκτονία των Ορόμο που είναι ένα σχεδόν συνεχές γεγονός το οποίο άρχισε στα μισά του 19ου αιώνα.

Ορόμο Ουακεφάτα, οπαδοί της παραδοσιακής μονοθεϊστικής και ανεικονικής θρησκείας τους, εορτάζουν την θρησκευτική εορτή Ιρίτσα.

Η διάλυση των αφρικανικών βασιλείων των Ορόμο και η γενοκτονία των Ορόμο οφείλεται στο γεγονός ότι οι κακουργηματικές και σατανικές ηγεσίες των αποικιοκρατικών χωρών του 19ου αιώνα, και πιο συγκεκριμένα οι κυβερνήσεις της Αγγλίας και της Γαλλίας, πούλησαν όπλα στο μικρό κρατίδιο των Αμχάρα και Τιγκράυ, την Αβησσυνία, για να κάνει πόλεμο εναντίον των Ορόμο και άλλων κουσιτικών και νειλοσαχαρικών εθνών, να τα κατακτήσει και να τα προσαρτήσει.

Έχει αποδειχθεί ότι κατά την περίοδο κατά την οποία αυτές οι δυο χώρες διεξήγαγαν μια παγκόσμια εκστρατεία εναντίον του δουλεμπορίου, επέτρεψαν στο μικρό και βαρβαρικό βασίλειο της Αβησσυνίας να διεξάγει δουλεμπόριο ώστε να έχει έσοδα και να αγοράζει όπλα. Οι τότε κατακτήσεις των άλλων ανατολικών αφρικανικών βασιλείων εκ μέρους των Αμχάρα και Τιγκράυ της Αβησσυνίας ήταν κανονικό χασάπικο επειδή εκείνα τα έθνη πολεμούσαν με ακόντια, τόξα, βέλη και σπαθιά. Έχει καταγραφεί από ουδέτερους παρατηρητές εκείνων των χρόνων ότι οι μισοί Ορόμο εσφαγιάσθησαν κατά την αβησσυνική κατάληψη της Ορομία.

Σήμερα μόνον σε κείμενα Ορόμο καθηγητών, ερευνητών και αναλυτών και σε άρθρα του καθ. Μουχάμαντ Σαμσαντίν Μεγαλομμάτη θα βρείτε την αλήθεια σχετικά με το θέμα. Όλοι οι άλλοι ερευνητές και ειδικοί είναι υποχρεωμένοι να σιωπούν γιατί το να μιλήσεις για την ιστορικώς πρώτη, την μεγαλύτερη, και την πλέον μακρόχρονη γενοκτονία των νεωτέρων χρόνων στις ανελεύθερες Ευρώπη, Αμερική και στα εξαρτήματά τους είναι κυριολεκτικά career terminator (τερματιστής σταδιοδρομίας).

Αλλά όταν ανέφερα σε Ορόμο υπαλλήλους κι εργάτες των εταιρειών που διευθύνω εδώ στην Κένυα ότι γνωρίζω προσωπικά τον Έλληνα ανατολιστή κι αφρικανολόγο κ. Μεγαλομμάτη που έκανε επί μακρόν μια media campaign υπέρ των Ορόμο, τα πρόσωπά τους έλαμψαν και μου ζήτησαν να τους τον γνωρίσω, γιατί τα περί των Ορόμο online άρθρα του της περιόδου 2004-2011 τυπώνονταν, μεταφράζονταν από τα αγγλικά στην γλώσσα των Ορόμο, και διαδίδονταν ανάμεσά τους ακόμη και στα πιο απόμακρα χωριά. Και μια φορά, όταν ο κ. Μεγαλομμάτης ήταν περαστικός από την Κένυα, τους έφερα σε επαφή και κείνοι τον αγκάλιαζαν και τον φιλούσαν σαν να ήταν εκείνος ένα μέλος της οικογένειάς τους. Και τι έκανε εκείνος; Μιλούσε τέλεια σε Αφαάν Ορόμο μαζί τους!

Αφαάν Ορόμο σημαίνει ‘γλώσσα των Ορόμο’ στην γλώσσα τους, όπως και Αφ Σομάλι σημαίνει ‘σομαλικά’ στην γλώσσα των Σομαλών, Αφαράφ σημαίνει γλώσσα ‘γλώσσα των Άφαρ’ στην γλώσσα εκείνου του έθνους, και Σινταμουάφο σημαίνει ‘γλώσσα των Σιντάμα’ στην γλώσσα του συγκεκριμένου κουσιτικού έθνους.

Αυτά τα αναφέρω για να καταδείξω την εγγύτητα των κουσιτικών εθνών και γλωσσών. Παραλλαγές του Αφ- σημαίνουν ‘γλώσσα’. Δηλαδή είναι όπως η λέξη lingua στις λατινογενείς γλώσσες. Τα Αφαάν Ορόμο, όπως και τα Σινταμουάφο και τα σομαλικά, γράφονται σήμερα με λατινικό αλφάβητο.

Οι Ορόμο χαρακτηρίζονται από θρησκευτική τριχοτόμηση: άλλοι είναι μουσουλμάνοι, άλλοι χριστιανοί και άλλοι Ουακεφάτα, δηλαδή πιστοί της Ουακεφάνα, της παραδοσιακής θρησκείας των Ορόμο.

Προ 200 ετών δεν υπήρχε ούτε ένας Ορόμο μουσουλμάνος ή χριστιανός.

Όταν όμως άρχισε η αβησσυνική κατάληψη που συνδυάστηκε με την εμφάνιση δυτικών ιεραποστόλων και την επιλογή ανάμεσα σε βίαιο εκχριστιανισμό ή θάνατο, πολλοί Ορόμο προσχώρησαν στο Ισλάμ και συνεργάστηκαν με τους Σομαλούς και την ιταλική αποικιοκρατική διοίκηση της Σομαλίας εναντίον των Αβησσυνών.

Σε πλήθος άρθρων του, ο κ. Μεγαλομμάτης έχει καταδείξει τις στενές σχέσεις και τις ομοιότητες ανάμεσα

α) στην αρχαία αιγυπτιακή θρησκεία,

β) την αρχαία κουσιτική / μεροϊτική θρησκεία στο προχριστιανικό Σουδάν (που οι αρχαίοι Έλληνες αποκαλούσαν ‘Αιθιοπία’) και

γ) την Ουακεφάνα. Ακόμη περισσότερο,

ο Έλληνας αφρικανολόγος έχει ιστορικά αποδείξει την μεροϊτική – κουσιτική καταγωγή των σημερινών Ορόμο της Αβησσυνίας και της Κένυας από το Αρχαίο Σουδάν (την πραγματική Αιθιοπία), έτσι δίνοντας στο μεγαλύτερο σύγχρονο κουσιτικό έθνος μια ιστορικότητα που πάει πίσω στο 2500 π.Χ. και τον πολιτισμό της Κέρμα στο σημερινό βόρειο τμήμα του Σουδάν.

Ουακεφάνα σημαίνει πίστη στον Ουάκο, τον μόνο Θεό κατά τους Ορόμο. Οι μουσουλμάνοι Σομαλοί, αν και χρησιμοποιούν το όνομα Αλλάχ, διατηρούν και την κουσιτικής (Cushitic) καταγωγής λέξη Ουάκο. Συχνά μάλιστα την προσθέτουν μετά από λέξεις με ευεργετικό νόημα: δεν λένε ‘μπαρ’ (: βροχή) αλλά ‘μπαρ Ουάκο’, δηλαδή ‘η βροχή του Θεού’!

Στην συνέχεια παραθέτω μια σειρά από συνδέσμους για πρώτη εξοικείωση με το θέμα (η wikipedia έχει συχνά πολλές ανακρίβειες για λόγους που ήδη προανέφερα: επικρατεί σκοπίμως μεγάλη παραπληροφόρηση σχετικά) και αναδημοσιεύω ένα τεράστιο άρθρο του κ. Μεγαλομμάτη στα αγγλικά, αρχικά δημοσιευμένο στις 2 Μαΐου 2010, με τίτλο Oromo Action Plan for the Liberation of Oromia and the Destruction of Abyssinia (Fake Ethiopia), δηλαδή Σχέδιο Δράσης των Ορόμο για την Απελευθέρωση της Ορομία και την Καταστροφή της Αβησσυνίας (Ψεύτικης Αιθιοπίας).

Το συνηθισμένο στην Ορομία πελώριο δέντρο Οντάα (Odaa) επέχει κεντρική θέση στην κοινωνία, την πίστη και την ζωή των Ορόμο.

https://om.wikipedia.org/wiki/Odaa

Σημειώνω ότι ο κ. Μεγαλομμάτης είχε συγκρουστεί με τον αιγυπτιολόγο ακαδημαϊκό και καθηγητή του Jean Leclant, ο οποίος ήταν αυτός που συνέστησε προσωπικά στον φίλο του, τον ματοβαμμένο Αμχάρα τύραννο της Αβησσυνίας Χαϊλέ Σελασιέ, στα μισά της δεκαετίας του 1950 (όταν ο Leclant ίδρυσε την εκεί Γενική Διεύθυνση Αρχαιοτήτων) να αλλάξει το όνομα της χώρας από Αβησσυνία σε Αιθιοπία.

Το γιατί συνέβη αυτό είναι μια μεγάλη ιστορία, η οποία θα απασχολήσει όλο τον κόσμο στο μέλλον, αλλά ο κ. Μεγαλομμάτης έχει επανειλημμένα γράψει για το θέμα και γι’ αυτό θα επανέλθω.

Κλείνω ζητώντας σας να μην αποκαλείτε πλέον Αντίς Αμπέμπα την πόλη που είναι πρωτεύουσα του τυραννικού αυτού κράτους. Το όνομα αυτό στάζει αίμα. Αυτή ήταν η πρωτεύουσα ενός από τα βασίλεια των Ορόμο τον 19ο αιώνα και ονομαζόταν Φινφινέ. Οι Ορόμο ακόμη την ονομάζουν έτσι – και μόνον έτσι.

Διαβάστε:

http://www.oromoliberationfront.org/News/2008/Open%20Letter%20to%20HRH.html

http://oromoliberationfront.org/english/oromia-briefs/

http://oromoliberationfront.org/english/finfinne-addis-ababa-is-an-oromo-land/

http://www.genocidewatch.org/ethiopia.html

http://www.voicefinfinne.org/English/History/MB.html

http://www.voicefinfinne.org/English/index_interview.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oromia_Region

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oromo_people

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oromo_language

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oromo_conflict

http://free-oromiyaa.blogspot.com/2010/05/oromo-action-plan-for-liberation-of.html

https://oromiatimes.org/2014/01/04/evidence-meneliks-genocide-against-oromo-and-other-nations/

Η σημερινή διοικητική διαίρεση της Αβησσυνίας (Ψεύτικης Αιθιοπίας) εκφράζει τα συμφέροντα των κατακτητών Αμχάρα και Τιγκράυ, των δυο εθνών της Αβησσυνίας που με κατακτητικούς πολέμους και γενοκτονίες επεξέτειναν τον 19ο και τον 20ο αιώνα τα σύνορα του μικρού και βαρβαρικού κρατιδίου τους που εκτεινόταν από την λίμνη Τάνα στην Αξώμη μόνον.

—————————————————

Oromo Action Plan for the Liberation of Oromia and the Destruction of Abyssinia (Fake Ethiopia)

First published in the American Chronicle, Buzzle and AfroArticles on 2nd May 2010

Republished in the portal of the exiled Oromo Parliamentarians

https://www.oromoparliamentarians.org/English/News_Archive/Oromo%20Action%20Plan%20for%20the%20Liberation%20of%20Oromia.htm

Dr. Muhammad Shamsaddin Megalommatis

The present article is not an original, new text; it consists in the merge of eight articles first published in 2008. The text has been slightly modified, edited and updated. As the series was not completed, I will further expand in forthcoming articles in order to extensively describe the types of actions needed to be undertaken by independent average Oromos in view of the liberation of Oromia and the ultimate destruction of the monstrous colonial tyranny of Abyssinia, the world´s most racist and inhuman state. The present article consists of 21 units, as per below:

1. The Search for Oromo Leadership

2. A New Oromo Leadership: A Global First

3. Weaknesses of the Traditional Political Leadership

4. Identification of the Oromo Nation in 2010

5. Who is the enemy of the Oromos?

6. Local – Regional-level Foes

7. Authentic Oromos and Fabricated Amharas; the Total Opposition

8. Direct and Indirect Colonialism

9. Differentiation among Colonial Rulers

10. Anglo – French Colonial Establishment: Arch-enemy of the Oromo Nation

11. Millions of Oromo Leaders Organized in Independent Groups

12. Present Oromo “Leaderships” and their Inertia

13. Key Figures to Be Considered by All the Oromos

14. Biyya Oromo Independent – Whose Work Is It?

15. Groups of Oromo Liberation Activity – GOLA

16. Ground work

17. GOLA Security – Impenetrability

18. GOLA – Commitment

19. GOLA – Function

20. Basic Directions for GOLA Projects and Endeavours

21. Collection of Information Pertaining to the Oromo Nation

——————————————–

1. The Search for Oromo Leadership

I went very attentively through Mr. Abdulkadir Gumi´s article ´Oromos: unblessed with leaders´ and I do find it as an excellent opportunity to exchange with my friend some ideas and approaches in public. Mr. Abdulkadir Gumi is a young Borana Oromo political activist, who deserves great respect for the help he has offered to many Oromo refugees, penniless refugees, and undeservedly imprisoned asylum seekers. In an opinion editorial, Mr. Abdulkadir Gumi asserted that the Oromo Nation has currently no great caliber political leaders able to “rise above their village, clans, interest”. Little matters whether I agree with the statement or not. Abdulkadir may be right in his comparisons with examples of African leaders, but I would like to pinpoint some yet unnoticed truths.

Point 1 – Worldwide lack of political (and not only) leadership

Searching worldwide, one can hardly find political leaders worthy of their titles. One can go through numerous editorials, analyses and even books about the subject. The issue is not quite new, but I would add that it gets continually deteriorated year after year, decade after decade. I came to first notice it in the 80s, when political commentators in Europe explained that the then generation of statesmen and politicians (Helmut Kohl, Hans Dietrich Genscher, Giulio Andreotti, Margaret Thatcher, James Callaghan, Francois Mitterrand, Jacques Chirac, Jimmy Carter, etc.) were of smaller caliber and poorer performance than the previous generation of European and American statesmen who reshaped Europe and America in the aftermath of WW II (Konrad Adenauer, Alcide De Gasperi, Winston Churchill, Harry Truman, Dwight Eisenhower, Charles de Gaulle, etc.).

I would add that ever since the same motif has been repeatedly employed within more specific contexts, academic, artistic, philosophical, spiritual, etc. Viewed as such, it is omnipresent in almost every era and every period of human civilization; only in few periods of zenith it is momentarily forgotten. This is the so-called ´concept of decadence´, according to which the past is always greater, higher, nobler, and consequently, more classic. People have always been familiarized with the concept that in the past ancestors were heroic, epic, and grandiose.

In fact, average people and political leaders change very little and their caliber is generally the same; what changes and in the process confuses our understanding is the era in which we live. Our acts and our thoughts, our quests and our hopes create instantly different contexts within which everything is viewed differently. Sometimes, this is also true, another context is truly a lower context, and then it would be impossible to expect greater thinkers, leaders, intellectuals and visionaries. The context is always reflected in the people who compose it, because they first express in it their deep thoughts, worries and perceptions.

Placing the subject within the context of our times, we can only agree with the approach; our era of conventionalism, materialism, relativism, conformism and subjectivism helps proliferate corrupt statesmen, crestfallen leaders, and conventional thinkers who are held captive of fallacies and forgeries that appear to them as awfully great and therefore impossible to challenge. These are the myths of our times that we avoid to demolish because this would deprive us of the hierarchical approval of our lethargic society where the manipulation is omnipresent and the fraud remains omnipotent.

Befallen societies – real, decomposed social corpses cannot by definition bring forth great leaders; when an overwhelming pan-sexism is matched with cynical individualism, which is measured in millions of dollars and reconfirmed by social bubbles, the so-called leaders and intellectuals are devoid of originality, in-depth knowledge, and humane understanding, let alone wisdom and erudition. Social solidarity takes then the form of soiree de gala whereby caviar and champagne do not allow the attendants to focus on the dramas of billions of impoverished and starving masses.

In the societies of the End, there will be no leader; not because there are not or there cannot be. But because by accepting to lead the present elites, they would defame to very concept of leadership – which they are certainly not ready to consent with. In fact, the situation observed by Mr. Abdulkadir Gumi among the Oromo society hinges on global developments of the last 50 years.

Point 2 – Political leadership and “realistic” solutions

Political leadership does not necessarily mean great personality, but effective delivery of realistic political solutions. This is a point of clash within some Oromo leaders; I believe some of them are truly great people who have been exposed to extreme experience opportunities and formed very strong personalities. The same concerns Oromo theoreticians, academics and intellectuals.

One must have a perspicacious sight in this regard; what is a value for these Oromo leaders and intellectuals is not necessarily a value for our present collapsed world. Delivery of realistic solutions by a political leader and statesman is conditioned by adequate acceptance of the values of the present world. Yet, one can be a great person and fail to deliver a realistic political solution; the measures of this world are such that impose debasement and ignominy as key to success.

People who insist on preserving their integrity have definitely poor chances to successfully deliver.

Point 3 – Political action results from correct plan and timing

Epicenter of efficient political leadership is the well-timed and correctly planned political action. This is not an easy task for leaders of organizations, fronts and movements that struggle for the national liberation of oppressed peoples. Most of them have grown in clandestine conditions without attending a school of political science, thought and action.

Many Oromo leaders of liberation fronts and organizations, before taking a vital decision, ignore the real dimensions of the issue concerned, and are not able to correctly evaluate whether their impending action´s timing is good or not. This can be remedied through collective forms of leadership and through further involvement of the Oromo academics in the various liberation fronts, organizations and associations.

There is a great number of Oromo academics and intellectuals, who except from serving as the oppressed nation´s scholarly assets, could definitely help Oromo political leaders renowned for their strong clandestine experience but also for their political unawareness. For the years ahead, it will be decisive to offer these Oromo academics and intellectuals key positions of councilors and advisors and let them define many non political and political aspects of the Oromo National Struggle for Independence.

In fact, all the Oromos must understand that the real fight starts now! It would therefore be wise to view the ´Oromia Tomorrow´ project from scratch and holistically. There is always time for a comprehensive plan, target prioritization, adversary targets´ analysis, and internationalization of the Oromo struggle for National Independence – which must make the headlines and the breaking news allover the world.

Point 4 – Oromo Voluntarism

At this moment, I will refer to an excellent sample of American voluntarism that is very closely affiliated with Oromo social stance; it is the classic quote from President John Kennedy´s inaugural address (20 January 1960):

“And so, my fellow Americans, ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country”.

This consists in the best answer to Mr. Abdulkadir Gumi´s call for great and honest Oromo leaders to appear. The best Oromo leaders are indeed the unknown Oromos, all those who spent time in jail, have been persecuted throughout Abyssinia, were mistreated by the Abyssinian agents of secret services abroad, and without losing their faith in the ultimate liberation and the rehabilitation of the Oromo Nation, they are ready to do all it takes to get it done.

This is not a figure of speech; it is literally meant.

The aforementioned quote of the assassinated American President was said for citizens of an established country; for the homeless Oromos, the quote could be paraphrased into the following:

“And so, my fellow Oromos, ask not who will be your leader in the struggle for Independence; ask yourselves how you will be the leader in the struggle for Independence”.

Instead of waiting known and unknown persons to perform and lead the Oromo Nation to Independence, the Oromo youth must truly understand that their contribution to the long desired objective of National Independence is as important as that of any leader.

Through political activism in a great number of fields, pioneering initiatives and proper political monitoring and analysis, young Oormos, acting within small nuclei and impenetrable groups, can exercise a great impact on all the liberation movements, fronts or organizations, and on their leaders.

2. A New Oromo Leadership: A Global First

This will truly be the transcendental approach to the existing need for Oromo leadership; instead of getting involved into endless discussions of the style “we did all we could”, “no, you did nothing”, “you are tribalists without future”, “you want to impose political prevalence of one tribe when the others pay”, “you are sectarian”, “no, you got bribed in order to stay inactive”, “you are wrong in willing to shape an alliance with those” “you are isolated from the rest” and a thousand of possibly true but utterly disastrous sentences like the aforementioned, the Oromos must reflect and emulate their traditions, culture, behavioural system, and historically attested identity.

Almost all the Oromos can be the leaders of the Struggle for Liberation of Oromia. Little matters whether finally some of them will be absent. In this series of articles, I will examine what and how the Oromos should act in order to trigger tremendous changes and momentous political developments that neither their vicious enemies, the racist ´Ethiopianist´ Amharas, nor any possible traditional Oromo leadership could ever outmaneuver, disregard, avert or avoid.

3. Weaknesses of the Traditional Political Leadership

Before proceeding systematically into methodological steps, one should stress a point:

Why is collective leadership, shared by thousands of Oromo political activists and social voluntarists, preferable to traditional political leadership?

I think one does not need much to underscore the importance of this seminal point. Traditional political leaderships involve leaders, and rely extensively on personal leadership. Personal leadership is the weakest point of a liberation struggle; this is not widely known. A person is easily exposed to influence, impact, pressure, demands, extortion, inducement, bribery and blackmail. A traditional leader is engaged in personal contacts, consultations and deliberations.

Consequently, one understands clearly that a traditional leader of a liberation front is exposed to the world of global power (involving mainly diplomacy, administration, military, and financial corporations); the liberation front´s objectives and deeds usually clash with interests of some parts of the world of global power, and then contacts are resumed in order to solve the issues.

In these contacts, the eventual liberation front leader is an extremely weak being compared with the professionals of the world of global power (be they a diplomat, a military, a Chief Financial Officer or a special envoy). Such is the difference that the few first attempts of enticement usually bring a wonderful result and the liberation front leader is then suitably ´bought up´.

There is more to it; the aforementioned eventuality is not immediately detected by the followers or the colleagues of the (already bought up) leader. He then proceeds smoothly (is even advised to do so by his ´buyers´ who now are called ´international support´) and in the span of a few months, he suddenly expresses a strange and unexpected suggestion; he may then influence all the rest or he may not. But even before that, the change is detected by the opponents of his earlier interlocutors. Who are they? Well, practically speaking, anyone belonging to another part of the world of global power. Do not view this situation necessarily limited within the frame of a well known concurrence in Africa, such as US – China, Europe – China, US – Europe; it can be an internal European or American group of power that is opposed to the one that first contacted and bought the liberation front leader.

What happens in this case is a counter-negotiation, a counter-blackmail, and a counter-bribery; with more money in his pockets (I am sorry, rather read Swiss bank accounts), the leader acts differently and accommodates himself in another country. With all the divisions that the new situation may create, as the world of global power has enough money for all; when colleagues separate from leaders there is always an enticement – counter-enticement issue involved.

Few leaders have today the strength of Che Guevara; people become smaller when the world of global power becomes stronger. Usual thoughts of today´s liberation front leaders, who have been bought up, are theoretical questions like the following:

Why being assassinated, when one can live a nice and comfortable life, have position, climb up to a world class respectability, and even hear acclaim and finally enjoy posthumous fame?

One could expand up to the level of an encyclopedia on this execrable issue that delineates the world corruption just ´minutes´ before an excruciating disaster sends all these illegal and inhuman interests to the Hell they deserve, but this is not the subject of this article.

From the aforementioned it becomes clear that collective leadership, established out of simple people who first situated the center of their activities in small independent cells of work before merging them, can avoid the entire chapter of enticement and blackmail attempted by the world of global power at the prejudice of personal leadership. Simple people, who worked in simple groups of volunteers and all together meet the representatives of the world of global power, automatically cancel the possibility of these shameful representatives to act in their customary way.

Let´s study a hypothetical, yet possible case. If 10 representatives of a union of activists´ groups meet with one or two French or English diplomats, what sort of colonial tactics can be attempted? They will reject the bribe offered (if the offer is ever expressed) and thus they will effectively interrupt the shameful negotiations. The representatives of the world of global power will be in total despair because they will have no means to influence this union of activists´ groups as the personal contact and the evil exercise of enticement and blackmail practices would prove to be impossible. The representatives of the world of global power become powerless if they cannot isolate one person out of an entire group or union of groups. With the 10 representatives rejecting the bribe, the representatives of the world of global power would not know whom to contact and how to influence this headless union groups. They would have to interfere in more expensive, painful or uncomfortable ways; their bias would be then revealed more easily.

There is more to it; before reaching the level of being convoked by some representatives of the world of global power, the union of activists´ groups will have already done tremendous work which would be absolutely disproportional to the fainéant and indolent pseudo-leaders of the traditional political leadership. Absolutely colossal work can be done, and will have been done even before the level of the establishment of the union of activists´ groups; the essential and background work must be done first, and will have to be done by the activists´ groups and isolated cells. Never forget, the representatives of the world of global power very often ask their puppets precisely this: to stay inactive. This helps tremendously their agendas at times.

This has very prejudicial side-effects. If one considers the work that needs to be done and the work that has been done by all the existing Oromo liberation fronts, one realizes automatically why Oromia has not yet been liberated. The detrimental comparison (certainly less than 1%) is due to the fact that the indolent leaders render the entire Oromo Nation indolent as well. Why bother if you think that a leader and an organization will manage it altogether? Relax! Contemplate the wonderful lines of the Oromia mountains´ peaks in the horizon, and expect the liberation to fall from the sky!

On the contrary, if you know that the liberation of your country is simply your own affair – and none else´s – then you are bound to act, ceaselessly, passionately and wholeheartedly. And who is the Oromo who would not give everything to see the black – red – white flag in the UN General Assembly?

4. Identification of the Oromo Nation in 2010

Before going ahead with the necessary fields of Oromo grassroots revolutionary cells and groups of work, we have to make a clear-cut demarcation of who can be members of such a group. In fact, only Oromos, either in Oromia or the Diaspora, can be members in these cells. Who can be considered as Oromo native in 2008?

Every person whose origin involves an Oromo father and/or mother, every person who speaks Afaan Oromo as native language, and every person who in addition to the aforementioned conditions is totally committed to the Struggle for the National Liberation and Independence of Oromia is an Oromo. Abiding by Gadaa social and behavioural values, rules and activities is imperative, and if for any possible reasons some Oromos may have partly or totally forgotten, neglected or abandoned Gadaa, related training and education must be offered to them – which is one more concern for the activists´ groups.

In addition to the aforementioned compulsory and incontrovertible conditions of Oromoness, one should provide for the integration within the Oromo society of all the people married with Oromos, and of their children, as long as they abide by the second and the third of the previous three conditions. Abiding by Gadaa values, rules and activities is always imperative, and related training and education must be offered to them as well.

Furthermore, for people exposed to and victimized by racist policies of assimilation, carried out by Oromos´ enemies who targeted the diachronic existence of the Kushitic Oromo Nation, there must be a provision. As result of the criminal anti-Oromo policies imposed tyrannically over the span of the last ca. 130 years, several Oromo natives lost their Afaan Oromo linguistic skills and even their identity. They should undergo – if this is explicitly demanded by them – an intensive course of Oromo identity rehabilitation which will also be a matter of concern and endeavour for the activists´ groups. They will have to learn Afaan Oromo, integrate themselves within exclusively Oromo social and professional context, and adhere to one of the two traditional Oromo religions, Waaqeffannaa or Islam. Not only a concern for their Oromization must be shared, but a vivid effort of de-Amharanization must be applied (upon their request), and their rejection of any element of the terrorist, racist theory of ´Ethiopianism´ must be total and absolute. Abiding by Gadaa values, rules and activities is imperative for them too, and related training and education must be offered to them. Under these conditions, and following their 18 to 24 months long training, they could be considered Oromos, and then participate in the Oromoo activists´ cells and groups of volunteers.

Finally, a provision must be made for the eventual Waaqeffannaa proselytes, and all those who may find in Waaqeffannaa a system of beliefs and practices that suits their mindsets and visions best, under condition of learning Afaan Oromo, and permanently ascribing themselves to Oromo social values, rules and activities (Gadaa).

Before focusing on the ways to establish Oromo cells of political activists and social volunteers, we must analyze a critical point; the lack of independence for the entire nation is not the result of mere coincidence. Real, criminal enemies have existed and are currently active against the Oromo Nation. No success will ever mark a socio-political project if foe identification is neglected or undermined.

5. Who is the Enemy of the Oromos?

This question can be phrased only by true Oromos; this means that not a single individual, who does not see his life purpose included in the effort for the Liberation – by all possible means – and National Independence of Oromia, has the right to speak in this regard.

As we already stipulated, there may be people whose ancestry is only partly Oromo; however, one cannot accept them as properly speaking Oromos (either they speak Afaan Oromo or not), as long as they do not fully admit the National Need for Independent Oromia and do not acknowledge that for them top life priority is the Liberation – by all possible means – of Oromia.

Consequently, people who are not Oromos, have no right to participate in the debate about Oromos, their liberation, and their enemies´ elimination. These pseudo-Oromos are alien, sick and evil elements that must be cut off from the Oromo Nation and adequately – and paradigmatically – punished.

In the same way an Englishman or a Russian will not tell the Georgians who their enemies are and what their national objectives should be, a non Oromo – by virtue of his rejection of, or opposition to, Independent Oromia – has nothing to say and should therefore be properly isolated.

In addition to the Native Oromos, historians and political scientists, analysts and commentators, fully committed to unadulterated truth and objective stance, have to participate in the national Oromo debate, and contribute to a critical political subject, such as the Oromos´ foe identification.

At this point, we must direct our analysis´ efforts to two different levels, first the local – regional platform, and second the regional – global arena.

6. Local – Regional-level Foes

Over the past few months, we observed an Abyssinian governmental effort to fuel disputes among Oromos inhabiting different parts of the occupied Oromia and other subjugated nations of the obsolete Abyssinian colonial state. There were clashes with the Sidamas, the oppressed nations of the Benishangul province, and others. Are these nations enemies of the Oromos?

This is a viciously setup trap; these nations have been incorporated in the obsolete Abyssinian colonial state without their political willpower and personal determination.

Other tyrannized nations are not enemies.

These oppressed nations have been forced to accept the reality of their lands´ invasion, their historical rulers´ and leaders´ physical annihilation, their properties´ confiscation, their houses´ destruction, their ancestors´ assassination or slavery, and their culture´s, religion´s and language´s prohibition. In brief, they have lived a dark national and personal experience similar to that of the Oromos.

Their socioeconomic and political manipulation by any Abyssinian tyrannical administration helps only further victimize them; the Oromos must understand that since they form the largest nation within the colonial hell Abyssinia (fallaciously re-baptized ´Ethiopia´), the criminal tyrannical rulers will certainly try repeatedly to oppose them by using all possible means – not only the governmental oppression.

1. Tigray Monophysitic (Tewahedo) Abyssinians are not enemies.

Many analysts and commentators use the term ´Tigray-led´ to describe Meles Zenawi´s tyrannical administration. There is no doubt about the origin of the Abyssinian dictator; equally, there is no doubt about the increased proportion of Tigrays hired and present in Abyssinia´s public administration. Under conditions of democratic rule, the Tigrays should not outnumber the Ogadenis hired in the public sector, ´elected´ in the parliament, and appointed in the government and the military, as the two nations´ total population comprised within Abyssinian borders is the same.

It would be inaccurate to identify the entire Tigray nation with Meles Zenawi´s tyrannical administration. First of all, the Tigrinya and Tigre speaking people live in great numbers outside Abyssinia, forming the majority of Eritrea.

Second, the Tigray Muslims, who represent a significant portion of the Tigray nation, are systematically persecuted in Abyssinia, and methodically kept out of the government.

Third, and more importantly, the Tigrays, as an independent nation with different identity, historical heritage, culture and traditions, are equally targeted by the state-imposed, historically false, and politically racist dogma of ´Ethiopianism´, which was setup by the Amhara Monophysitic Abyssinians in order to ensure the criminal project and evil plan of the assimilation (amharanization) of all the subjugated nations of Abyssinia with the Amharas.

In a way, Tigray traitor Meles Zenawi contributes to an Anti-Tigray, Anti-Abyssinian racist theory that greatly and irreparably damages his own nation. The same concerns all his followers, as well as every Tigray ascribed to the evil theory of Ethiopianism which is promoted by the Ethio-fascist crooks of Kinijit and Ginbot-7, Hitler´s children in Africa.

But there are Tigrays who reject the evil Amhara racism and their bogus-historical dogma, and Oromos must reach out to them and setup structures of future cooperation to comprehensively destroy Ethiopianism, and isolate the evil Amhara racists.

2. Amharas: the Insidious Invaders, Criminal Settlers, and Monstrous Tyrants

Before explaining why the Amharas consist in the focus of evil and anti-Oromo criminality, I want to quote an excellent study carried out by Sandra F. Joireman and Thomas S. Szayna, researchers of the Rand Corporation, who drew pertinent conclusions as regards the nature of the Amhara ideology, as ´insidious´: (http://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1188/MR1188.ch5.pdf):

“The long stretch of Amhara leaders in Ethiopia has led to two inaccurate and insidious ideas among the Amhara. The first is the association of a particular Amhara “type” with the definition of Ethiopian: by this notion, an “Ethiopian” is a slight, light-skinned, Christian, Amharic-speaking farmer. The second is a sense of manifest destiny: an idea that the Amhara are somehow ordained to rule a “Greater Ethiopia.” These ideas are insidious because they give no quarter to the majority of the population who do not fit this “type” linguistically, religiously, or ethnically”. (p. 12)

7. Authentic Oromos and Fabricated Amharas; the Total Opposition

The historical reality is simple and easy for all the Oromos to learn, understand, admit and thence use as basis for their political orientation. It is encapsulated in the foreign points:

1. Oromos and Amharas originate from different ethno-linguistic groups which opposed one another over the ages; the former are the descendants of the indigenous Kushites, the real ancient Ethiopians who developed a most ancient and illustrious civilization on the Nile´s banks in Northern Sudan (the real Ethiopia of the Ancient Greek and Latin sources) from the 3rd millennium BCE down to the middle of the 2nd millennium CE (involving three great Ethiopian Christian states, Nobatia, Makuria and Alodia). The Amharas are an Ancient Yemenite, Semitic, offspring that crossed the Red Sea and settled in the Eastern African coastland of today´s Eritrea before expanding in the inland.

The difference between Amharas and Tigray Abyssinians may even reflect different Yemenite settlements in Eastern Africa, but the Ethiopian Kushites had been in constant conflict with the Abyssinians even before the Abyssinian invasion of Ethiopia (Northern Sudan) and destruction of Meroe (the last pre-Christian Ethiopian capital) at 360 CE.

2. African Oromo Kushitic opposition to the Abyssinian Semitic presence in Africa is noticeable throughout the Christian, Islamic and Modern periods of Eastern African History. Quite characteristically, although Christian Abyssinians invaded Meroe, they failed to be accepted by the indigenous Ethiopians, the ancestors of the Oromos, and to diffuse Christianity in the Nile´s valley. Christianity was diffused in Ethiopia (Ancient Sudan) through Egypt.

3. The interconnection between the three Christian Ethiopian states and Christian Abyssinia was minimal, if not inexistent, until the demise of the Abyssinian Axumite state in the advent of Islam (ca. 650).

4. The three Christian Ethiopian states survived during the first period of Islamic expansion, whereas Christianity in Abyssinia was demolished with the rise of Islamic control over the Eastern African coastlands in the Red Sea area. The contacts between the isolated remnant of inland Axumite Abyssinia with the three Christian Ethiopian states were very limited.

5. The rise of the Kushitic Agaw Christian dynasty in the middle of 10th century in a small part of the present Tigray and Afar provinces´ territory helped Christianity survive in Abyssinia, but it consists in an abrupt dynastic, cultural, and national discontinuity. The Christian Agaw state was small and equally isolated. It resumed few contacts with the two Christian Kushitic Ethiopian states (Nobatia and Makuria merged to confront the Islamic pressure in 10th century Upper Egypt, whereas Alodia was comfortably far). However, it was deeply reviled by the disparate, revengeful Abyssinian elements that were wisely kept out of control. It finally collapsed because of their conspiracy.

6. The subsequent rise of the barbaric, criminal, adulterous, and evil pseudo-Solomonic dynasty in the 13th century opened the gates of the Hell for a multitude of civilized African nations who – with the Agaws first – became the target of the criminal Amhara forgers who introduced the counterfeit, spurious theory that the Axumite Abyssinians king had descended from the Biblical Queen of Sheba, an unhistorical Ancient Yemenite ruler (known as Balqis in the Islamic traditions that reshaped the Biblical and the Talmudic references), and the Ancient Israelite king Solomon.

7. There is not a single pre-Agaw or Agaw evidence (religious-historical, archeological or philological) that pre-Christian and Christian Axumite Abyssinians had ever believed that they had any sort of connection with the mythical Yemenite queen and the historical Hebrew king. It is all a criminal lie that kills millions of humans, and enslaves and tyrannizes all the rest who may come to an encounter with it.

8. This bastard theory reflected the projection of illegitimate needs of the Semitic Amharas on the Kushitic Agaw throne, and was used as political ideology by the theocratic, lunatic Amhara kingdom´s elite in their effort to serve and promote their heinous, utterly inhuman and antihuman objectives, namely Anti-Islamic hatred, Anti-African odium, and systematic barbarization and assimilation of all the Eastern African nations.

9. Following historical clashes with Christian and Muslim nations (Agaw, Afars, Somalis, Hadiyas), the Amharas – who did not bother to save the ailing Christian kingdom of Alodia (the last Christian Ethiopian kingdom in Sudan) when it was (ca. 1500 – 1520) attacked by the Funj Muslims – engaged in confrontation with the Oromo Nation, which lasted for centuries before the Oromos were (almost in their entirety) enslaved by the Abyssinians.

10. A pattern of the utmost importance in this confrontation is the persistent Amhara malignancy to act in premeditated manner matched with hypocrisy, duplicity, mendacity and to intentionally target the very existence of the Oromo Nation.

11. The fact that during the long historical process some disoriented, deceived or disenchanted Oromos entered into any sort of contact and relationship with the Amharas, involving even royal marriages, does not change in anything the reality that for every Amhara action and/or initiative there has always been a proven Amhara plan of racist, anti-Oromo nature, which was unveiled after each planned event had been unfolded.

12. The eventuality of a half-Oromo ancestry for an Amhara ruler means nothing but an Amhara Anti-Oromo plan. It would be otherwise only if, due to the eventual half-Oromo ancestry, the Amhara ruler denied the heretic, pseudo-Christian Monophysitic Abyssinian Church and introduced Waaqeffannaa religion among the Amharas.

If such an action had been taken, then we could have discussed about the fair and bi-dimensional character of the relationship between the two nations. When an Oromo gets absorbed within the Amhara socio-behavioural system (do not call it ´culture´), he / she becomes a non-issue and a non-subject for the Oromo National History.

13. Part of the Amhara pseudo-royal obscenity was the permanent practice to force marriages between people of supposedly noble origin and vulgar felons to enable the permanence of the theocratic control over the supposed ´palace´ of the Amhara Abyssinia. The practice started with the first pseudo-king of the bogus-Solomonic “dynasty”, Yekuno Amlak, who was the son of nobody, but was presented as the descendant of the last king of Axum, which would make even chimpanzees laugh!

14. On all this background, 13 – 14 decades of deliberate, coldhearted genocide perpetrated against the Oromos by the Amhara invaders, the terrorist Amhara settlers, the notorious Nafxagna, and the accompanying cruel soldiers was added to irreversibly stamp an irreconcilable relationship, which will end only with the liberation of the Oromos, the total separation of the two nations, the expulsion of the Amhara settlers from Finfinnee, Shoa and Gojjam, and the UN patronage of the two separate states´ relationship.

The Amhara anti-Oromo animosity reflects today a 2-millennium long opposition between the indigenous, African, Kushitic Ethiopians and the emigrant, Semitic, Yemenite Abyssinians. It should however be clearly understood that the Amharas are not the only enemy of the Oromos. Simply, the propinquity makes them more reviled.

For a subjugated nation, a faraway enemy can be more harmful and perilous; one can generally call the case ´colonialism´; however, this phenomenon is vast and nuanced. There can be direct and indirect colonialism. This is one point; the other point is that not all the colonial powers have been equally detrimental to the colonized peoples. It is essential to illuminate these two point before proceeding with the identification of the Oromos´ regional – global enemies.

8. Direct and Indirect Colonialism

Yemen, as integral part of the Islamic World for no less than 900 years, became normally an undisputed province of the Ottoman Empire, when the Sultans of Istanbul became Caliphs, and the Ottoman forces arrived in Yemen. Colonialism in Yemen started in the 1830s with the British invasion of Aden in their vicious plan of encircling and destroying the Islamic Caliphate – quintessence of the Islamic World. This example is a typical direct colonialism. The departure of the British brought an end to the direct colonial rule.

The British had also colonized the Ottoman province of Sudan in the second half of the 19th century; but to do this, they involved the Egyptians who were by then under a particular regime of a Viceroy who was nominally subject to the Ottoman Empire (as Egypt had been an integral part of the Caliphate for almost 300 years / 1517 – 1798) and essentially controlled (and therefore colonized) by the combined colonial forces of France and England. The military and economic presence of Europeans in Sudan was pseudo-legitimized by the idiotic cooperation of the Viceroy (Khedive), who was not even an Egyptian but Albanian of descent. This case is a composed, indirect and direct colonial, regime.

In the case of the colonial Abyssinian expansion at the prejudice of numerous African nations which lost their independence in the process, we have sheer French and English offer of support, technical assistance, financial aid, military know how transfer, and key intelligence info handed over the Abyssinian tyrannical rulers.

Both, France and England, wanted Abyssinia to expand colonially in order to

1. contain the Italian colonial expansion in the Red Sea and the Horn of Africa region, and

2. balance their own colonial expansion in the aforementioned area. The French were pushing from the West (Sahara and the territories of today´s Central African Republic and Chad), and the English were trying the establish a colonial axis from the North to the South of the Black Continent.

Consequently, the nations that have been subjugated by the Abyssinians, have been indirectly colonized by the British and the French. This is a key point to take into consideration.

In fact, indirect colonialism can last longer and take different forms; England colonized India, and after more than 200 years of colonial conspiracy, presence and rule, the English left. By dividing their previous colony, through a disreputable UN involvement, into many countries, the English managed that an entire nation, the Baluchs, be divided among three states, namely Pakistan, Iran and Afghanistan.

The treatment that the Baluchs have received within Pakistan is purely colonial, but the direct colonial presence of the Pakistani authorities in Baluchistan does not minimize in anything the indirect – still present – English colonialism.

A similar case can be noted in NW Africa, whereby the ongoing, indirect French colonialism left the Kabylian Berbers without a state.

9. Differentiation among Colonial Rulers

Colonialism itself is a vast issue that does not belong exclusively to modern periods of the History of the Mankind. In the Antiquity, we easily identify Egyptian, Phoenician, Assyrian – Babylonian, Aramaean, Persian, Yemenite, Greek, Hebrew and Roman colonies.

The reasons that bring the settlers to faraway places vary; from commercial motifs to military conquest, and from interest for exploration to flight due to tyranny, many varied motives bring people – sometimes in great numbers – to distant places.

In modern times, colonialism started with the efforts of the kings of Spain and Portugal to reach out to India in order to break the Ottoman monopoly over the commercial routes to the spices, fragrances, incense and other products of the Orient. Spanish colonialism proved to be extremely brutal as it took the form of intentional genocide of the Mayas, the Aztecs and the Incas, who were forced to Christianity.

Holland, France, and England followed on the Spanish and Portuguese colons´ footprints; contrarily, great maritime powers of the Mediterranean, like Genoa and Venice, remained confined within the same geographical area and gradually lost their significance. Although parts of Africa and Asia had been colonized by some of the five European colonial powers, first America was completely colonized (by Spain, Portugal, France, Holland, England and Russia), and then the competition was transferred in Africa where for centuries the Ottoman Empire controlled lands inhabited by Muslims that totaled an area of more than 8 million km2.

As all African Muslims (with the exception of the Moroccans, the Malians and other Muslims of the Western confines of Africa who were organized in at times sizeable states) from Algeria to Egypt to Somalia viewed the Sultan – Caliph and the Sheikh-ul-Islam as their political and spiritual leaders, we cannot possibly discuss of Ottoman colonialism.