Molecule Of The Day: Chloroform

Molecule of the Day: Chloroform

Chloroform (CHCl3) is a colourless, dense liquid that is immiscible with water at room temperature and pressure. Popularised by movies and dramas, it is often cited as an incapacitating agent in popular culture.

Chloroform was used as a general anaesthetic due to its ability to depress the central nervous system, a property that was discovered in 1842. This produced a medically-induced coma, allowing surgeons to operate on patients without them feeling any pain.

However, chloroform was found to be associated with many side effects, such as vomiting, nausea, jaundice, depression of the respiratory system, liver necrosis and tumour formation, and its use was gradually superseded in the early 20th century by other anaesthetics and sedatives such as diethyl ether and hexobarbital respectively.

While chloroform has been implicated in several criminal cases, its use as an incapacitating agent is largely restricted to fiction; the usage of a chloroform-soaked fabric to knock a person out would take at least 5 minutes.

Chloroform is metabolised in the liver to form phosgene, which can react with DNA and proteins. Additionally, phosgene is hydrolysed to produced hydrochloric acid. These are believed to cause chloroform’s nephrotoxicity.

Chloroform is often used as a reagent to produce dichlorocarbene in situ via its reaction with a base like sodium tert-butoxide. This is a useful precursor to many derivatives. For example, the dichlorocarbene can be reacted with alkenes to form cyclopropanes, which can be difficult to synthesise otherwise.

Chloroform is industrially synthesised by the free radical chlorination of methane:

CH4 + 3 Cl2 –> CHCl3 + 3 HCl

It can also be synthesised by the reaction of acetone with sodium hypochlorite in bleach by successive aldol-like reactions:

More Posts from Philosophical-amoeba and Others

One of my favorite things about working with archival materials is the opportunity to see earlier iterations of familiar, everyday items, such as this 1870 U.S. passport for chemical engineer Samuel Phillip Sadtler (1847-1923). While the text of the passport echoes that of contemporary ones (albeit in fancier script!), the size of the paper compared to today’s passbooks is staggering and the description of the passport holder is just delightful. In the absence of a photograph, we are advised that Sadtler, aged 22, has a “high” forehead, “straight” nose, “small” mouth, and “long” face, among other distinctive qualities. And since beauty is in the eye of the beholder, I wonder if there was some kind of standard for judging a forehead “high” or a face “long,” but perhaps that’s an archival find for another day.

Photo credits: Samuel P. Sadtler materials, 1867-1893. CHF Archives (accession 1989:02).

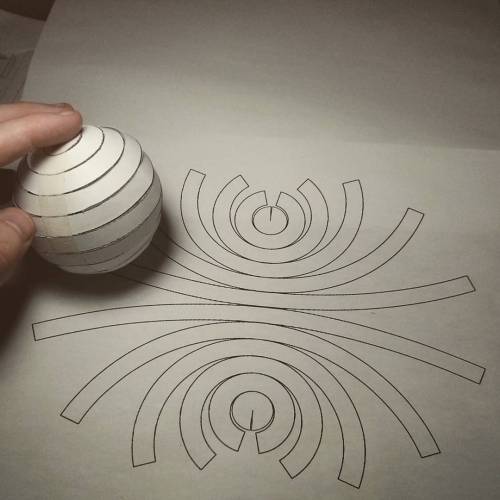

Can you flatten a sphere?

The answer is NO, you can not. This is why all map projections are innacurate and distorted, requiring some form of compromise between how accurate the angles, distances and areas in a globe are represented.

This is all due to Gauss’s Theorema Egregium, which dictates that you can only bend surfaces without distortion/stretching if you don’t change their Gaussian curvature.

The Gaussian curvature is an intrinsic and important property of a surface. Planes, cylinders and cones all have zero Gaussian curvature, and this is why you can make a tube or a party hat out of a flat piece of paper. A sphere has a positive Gaussian curvature, and a saddle shape has a negative one, so you cannot make those starting out with something flat.

If you like pizza then you are probably intimately familiar with this theorem. That universal trick of bending a pizza slice so it stiffens up is a direct result of the theorem, as the bend forces the other direction to stay flat as to maintain zero Gaussian curvature on the slice. Here’s a Numberphile video explaining it in more detail.

However, there are several ways to approximate a sphere as a collection of shapes you can flatten. For instance, you can project the surface of the sphere onto an icosahedron, a solid with 20 equal triangular faces, giving you what it is called the Dymaxion projection.

The Dymaxion map projection.

The problem with this technique is that you still have a sphere approximated by flat shapes, and not curved ones.

One of the earliest proofs of the surface area of the sphere (4πr2) came from the great Greek mathematician Archimedes. He realized that he could approximate the surface of the sphere arbitrarily close by stacks of truncated cones. The animation below shows this construction.

The great thing about cones is that not only they are curved surfaces, they also have zero curvature! This means we can flatten each of those conical strips onto a flat sheet of paper, which will then be a good approximation of a sphere.

So what does this flattened sphere approximated by conical strips look like? Check the image below.

But this is not the only way to distribute the strips. We could also align them by a corner, like this:

All of this is not exactly new, of course, but I never saw anyone assembling one of these. I wanted to try it out with paper, and that photo above is the result.

It’s really hard to put together and it doesn’t hold itself up too well, but it’s a nice little reminder that math works after all!

Here’s the PDF to print it out, if you want to try it yourself. Send me a picture if you do!

Chai Tea

Word for tea in most of the world’s languages are all ultimately related, belonging to two groups of terms.

“Tea” itself belongs to one of those groups. It was a borrowing from Dutch thee, in turn from tê, the reading of 茶 in the Amoy dialect of Min Nan. Those languages whose introduction to tea was primaraly from Dutch traders typically use words likewise derived via the Dutch thee. The Polish herbata is also part of this family, though slightly obscured, being a borrowing from the Latin herba thea.

The other major group is represented by the word chai, a more recent borrowing in English. Chai was borrowed from the Hindi cāy, which in turn came from a Chinese dialect with a form similar to Mandarin chá. Languages that use chai-type terms generally were first introduced to tea through overland trade, ultimately to northern China, while those that use tea-type terms were generally introduced to it via sea trade, from Southern China.

Both tê and chá are derived from the same Middle Chinese form, ultimately derived from Proto-Sino-Tibetan *s-la “leaf”.

When my alcoholic uncle died - and how it impacted my life as a nurse

A recent post from another nurse was so beautifully honest and vulnerable that it made me lose my snark and just get human for a minute. So I will share an experience and I have permission from all involved. I had an uncle who was a terrible alcoholic. It ravaged every aspect of his life, his work as a union tradesman, his ability to be a father or husband and his relationships with his brothers and sisters. My mom and I often visited him when he’d get admitted to the floor. I could never bear to see him in the ER. Dirty, belligerent, withdrawing in the DTs. I was embarrassed because I knew he was a frequent flier. I was embarrassed that I was embarrassed. We tried to drop him groceries and buy his Dilantin every month, but he moved around a lot, mostly renting rooms above taverns. He wanted nothing to do with sobriety. He used drugs when he could, but whiskey was his poison. In the end he only tolerated a few beers a day to keep away the shakes. To any nurse or medic or doc who new him he was a local drunk, but to me he was my uncle. I knew him as a kind loving man as well. I remember family BBQs and him tossing me up in the air as a kid. I remember him showing up drunk to thanksgiving and not making it out out of the car before passing out. I remember the disappointment in my family’s faces. I remember the shame in his eyes. I remember driving around his neighborhood looking at the entrances of taverns to see if he was passed out. I wondered if anyone would know to call us if he died. I wondered if he even had any I.D. But they did call. And I knew when I saw him at age 55 in the ICU Weighing 90 lbs dying of Hep C and esophageal CA that he didn’t have a lot of time left. I was a nursing student and an ER tech but I knew in my heart this time was different. I saw people fear him. I saw nurses treat him as if he was a leper. One yelled at him to be still while she gave him a shot of heparin and he grimaced in pain. Nurses came in one by one to start a heplock and he grimaced in pain. Despite knowing better after the 4th nurse was unsuccessful I begged them to stop and give him a break. My hospital I worked accepted him into impatient hospice. I was relieved. When he arrived I saw the 2 EMTs toss him on the hospice bed and walk out without saying a word while he grimaced in pain. They probably got held over and he probably didn’t seem like an urgent transport. They didn’t want to touch him. I didn’t say anything. I was scared to touch him too. He was emaciated with a huge head and a gaunt appearance. I wondered if he had AIDS. I felt bad for thinking that. I still kissed his forehead and told him he was going to be okay. Because I loved him. He was my family. And then I saw nurses treat him with kindness. I saw the beauty of a non judgemental hospice team make his last 96 hours on Earth a time where he could make peace with his demons. I saw Roxy drops for the first time and I saw him get some relief from the pain of untreated cancer, from the pain of dying. I saw them allow me break the rules and lift his frail body into a wheelchair, fashion an old fashioned posey to hold him up and take him down stairs for his last cigarette on Route 30. I was able to spend my breaks with him. I got to suction him and help give him a bed bath. I got off my 3-11 shift and spend a few hours with him watching a baseball game on replay. I sat with him in silence and I held his hand. I finally knew what people meant when they said the dying watch their life play out in their minds. I swear I could see it happening. I asked him if he was thinking about things he said “yep”. I asked him if he wanted me to stay or go and he said “stay”. So I stayed. I heard the death rattle for the first time. I cried to a veteran hospice nurse and she explained how the Scopolamine patch would help. I finally felt what it was like to be helpless to a family member in need and her words of comfort and years of experience meant everything to me. She said he probably had 48 hours at the most. I read “Gone from my sight” the blue book of hospice by Barbara Karnes. The whole family trickled in. His kids, all his brothers and sisters and nieces and nephews. His children told him they loved him and they forgave him. We kissed his forehead and washed his hair. My mother shaved his face. His daughter said words of kindness that relieved him of any guilt or regret. I saw this beautiful cousin of mine watch me suction him and she asked how I could be so calm and so strong. I didn’t feel strong or knowledgeable but when you are the “medical person” in the family they see things in you that you didn’t know you had. We surrounded him with love and light and he died surrounded by everyone who ever meant anything to him. The nurses even cried. I got to see the dying process for what it was. It was beautiful and at the same time so humbling it brought me to my knees. I have never forgotten that feeling and I pray I never do. Is alcoholism a disease? We debate it as health care providers and wonder about the others whose lives have been impacted by the actions of an alcoholic. The amends that never got made. I guess I don’t care if it’s a disease, a condition, or a lifetime of conscious choices and poor judgement. In the end it’s a human being, usually a dirty foul smelling human being with missing teeth who may or may not be soiled in urine and vomit. Sometimes kicking, hurling obscenities, racial slurs, or spitting. Often doing all of the above at once. It’s hard to empathize with a human being who arrives packaged up that way. It’s hard to care or to want to go above and beyond. And I don’t think you should ever feel guilty if you don’t have those feelings. That is okay. It’s natural to wonder about the damage these people may have done to others. Wonder how many lives they might have ravaged. Please don’t take their pain as your own. At least try not to. It is not your pain to carry. And we all know that is easier said than done. But please, Treat them with dignity. They feel. They hear you. Give them the care you know you are capable of giving. I can tell you I hold a special place in my heart for every nurse who touched my uncle with a gentle hand. Who cleaned him for the fifth time when he was vomiting stool. Who asked him to smile. Who smiled back at him. Who stroked his forehead and put a cool washcloth on it. I am eternally grateful for anyone that saw beyond his alcoholism and saw a person. A human. A child of God (if you believe in God). A father. A son. An uncle. And I believe in my heart he felt the same way, even if he didn’t or couldn’t say it. If you have that patient. That difficult, hard to like, dreadful patient. Don’t think you have to love them or even like them. You don’t. But if you can preserve their dignity and show them the kind of nursing care that anyone would deserve, than you are good. You are the reason we are the world’s most trusted profession. And even though you don’t know it, someone saw and felt it, and it meant the world to them. Go to bed and sleep soundly because you deserve that. - J.R. RN

1971 Japanese re-release poster for THE GRADUATE (Mike Nichols, USA, 1967)

Designer: unknown

Poster source: Heritage Auctions

Celebrating the films of storyboard artist Harold Michelson and researcher Lillian Michelson–the subjects of the upcoming HAROLD AND LILLIAN - A HOLLYWOOD LOVE STORY. This weekend, TCM will mark the 50th anniversary of The Graduate—a film that Harold storyboarded and contributed an iconic shot to—by screening a 4K restoration of the film in 700 theaters nationwide on April 23 and 26. Read more at the Harold and Lillian blog and find out where to see The Graduate here.

HAROLD AND LILLIAN opens next Friday at the Quad Cinema in New York.

Ornithorhynchus anatinus - Detail of Bill

The monotremes (egg-laying mammals) are the only mammalia with any sort of electroreception ability, and the platypus’ ability is far stronger than that of the echidna. They use neither sight nor smell while hunting for their food, which consists of small crustaceans and molluscs buried in lakes and slow-moving river bottoms. The platypus finds its food by sweeping its broad bill back and forth along the sediment, and the receptors that line the front and part of the sides of the bill pick up the electric field given off by its prey. It then uses its paws (with the flipper-ish part folded back) to dig out its snack.

Illustrations from the Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, Vol. I: Mammalia. 1848-1860.

Starting in the mid-seventh century, the Japanese government placed a ban on eating meat which lasted on and off for over 1,200 years. Probably influenced by the Buddhist precept that forbids the taking of life, Emperor Tenmu issued an edict in 675 CE that banned the eating of beef, monkeys, and domestic animals under penalty of death. (Side note: monkey must have been very popular to be named specifically in the law!) Emperor Tenmu’s original law was only meant to be observed between April and September. But later laws and religious practices essentially made eating most meat, especially beef, illegal or taboo.

It was not until 1872 that Japanese authorities officially lifted the ban. Even the emperor had become a meat eater, to show it was totally okay and not angering Buddha. While not everybody was immediately enthused, particularly monks, the centuries-old taboo on eating meat soon faded away.

Aphasia: The disorder that makes you lose your words

It’s hard to imagine being unable to turn thoughts into words. But, if the delicate web of language networks in your brain became disrupted by stroke, illness or trauma, you could find yourself truly at a loss for words. This disorder, called “aphasia,” can impair all aspects of communication. Approximately 1 million people in the U.S. alone suffer from aphasia, with an estimated 80,000 new cases per year. About one-third of stroke survivors suffer from aphasia, making it more prevalent than Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis, yet less widely known.

There are several types of aphasia, grouped into two categories: fluent (or “receptive”) aphasia and non-fluent (or “expressive”) aphasia.

People with fluent aphasia may have normal vocal inflection, but use words that lack meaning. They have difficulty comprehending the speech of others and are frequently unable to recognize their own speech errors.

People with non-fluent aphasia, on the other hand, may have good comprehension, but will experience long hesitations between words and make grammatical errors. We all have that “tip-of-the-tongue” feeling from time to time when we can’t think of a word. But having aphasia can make it hard to name simple everyday objects. Even reading and writing can be difficult and frustrating.

It’s important to remember that aphasia does not signify a loss in intelligence. People who have aphasia know what they want to say, but can’t always get their words to come out correctly. They may unintentionally use substitutions, called “paraphasias” – switching related words, like saying dog for cat, or words that sound similar, such as house for horse. Sometimes their words may even be unrecognizable.

So, how does this language-loss happen? The human brain has two hemispheres. In most people, the left hemisphere governs language. We know this because in 1861, the physician Paul Broca studied a patient who lost the ability to use all but a single word: “tan.” During a postmortem study of that patient’s brain, Broca discovered a large lesion in the left hemisphere, now known as “Broca’s area.” Scientists today believe that Broca’s area is responsible in part for naming objects and coordinating the muscles involved in speech. Behind Broca’s area is Wernicke’s area, near the auditory cortex. That’s where the brain attaches meaning to speech sounds. Damage to Wernicke’s area impairs the brain’s ability to comprehend language. Aphasia is caused by injury to one or both of these specialized language areas.

Fortunately, there are other areas of the brain which support these language centers and can assist with communication. Even brain areas that control movement are connected to language. Our other hemisphere contributes to language too, enhancing the rhythm and intonation of our speech. These non-language areas sometimes assist people with aphasia when communication is difficult.

However, when aphasia is acquired from a stroke or brain trauma, language improvement may be achieved through speech therapy. Our brain’s ability to repair itself, known as “brain plasticity,” permits areas surrounding a brain lesion to take over some functions during the recovery process. Scientists have been conducting experiments using new forms of technology, which they believe may encourage brain plasticity in people with aphasia.

Meanwhile, many people with aphasia remain isolated, afraid that others won’t understand them or give them extra time to speak. By offering them the time and flexibility to communicate in whatever way they can, you can help open the door to language again, moving beyond the limitations of aphasia.

David Bowie (1947-2016) at Kyoto - Japan - 1980

Photos by Sukita Masayoshi 鋤田 正義

-

majiida liked this · 3 years ago

majiida liked this · 3 years ago -

alchimiste-etoile reblogged this · 4 years ago

alchimiste-etoile reblogged this · 4 years ago -

drbr13111 liked this · 5 years ago

drbr13111 liked this · 5 years ago -

lilpiscesvenus liked this · 5 years ago

lilpiscesvenus liked this · 5 years ago -

theusualjasper liked this · 5 years ago

theusualjasper liked this · 5 years ago -

scarandtear liked this · 5 years ago

scarandtear liked this · 5 years ago -

letsflytoparis liked this · 5 years ago

letsflytoparis liked this · 5 years ago -

horny999 liked this · 5 years ago

horny999 liked this · 5 years ago -

dalonelybreadstick reblogged this · 5 years ago

dalonelybreadstick reblogged this · 5 years ago -

dalonelybreadstick liked this · 5 years ago

dalonelybreadstick liked this · 5 years ago -

dadcollectr liked this · 5 years ago

dadcollectr liked this · 5 years ago -

vidavelha reblogged this · 5 years ago

vidavelha reblogged this · 5 years ago -

huhhuheeee liked this · 5 years ago

huhhuheeee liked this · 5 years ago -

moksoriwa liked this · 5 years ago

moksoriwa liked this · 5 years ago -

franissad reblogged this · 5 years ago

franissad reblogged this · 5 years ago -

pandahoernchen liked this · 5 years ago

pandahoernchen liked this · 5 years ago -

daddy-bayern liked this · 6 years ago

daddy-bayern liked this · 6 years ago -

honeysweetthalia reblogged this · 6 years ago

honeysweetthalia reblogged this · 6 years ago -

honeysweetthalia liked this · 6 years ago

honeysweetthalia liked this · 6 years ago -

twixie98 liked this · 6 years ago

twixie98 liked this · 6 years ago -

infernal-fox liked this · 6 years ago

infernal-fox liked this · 6 years ago -

subjectaash-maxx liked this · 6 years ago

subjectaash-maxx liked this · 6 years ago -

mikeecho33 reblogged this · 6 years ago

mikeecho33 reblogged this · 6 years ago -

katheluu liked this · 6 years ago

katheluu liked this · 6 years ago -

chaotic-evil-rogue liked this · 6 years ago

chaotic-evil-rogue liked this · 6 years ago -

butwithglasses liked this · 6 years ago

butwithglasses liked this · 6 years ago -

its-mega-charizard-x liked this · 6 years ago

its-mega-charizard-x liked this · 6 years ago -

mind0ve liked this · 6 years ago

mind0ve liked this · 6 years ago -

whytho9 liked this · 6 years ago

whytho9 liked this · 6 years ago -

cokeandsodomy liked this · 6 years ago

cokeandsodomy liked this · 6 years ago -

shes666searchingrevenge liked this · 6 years ago

shes666searchingrevenge liked this · 6 years ago -

shes666searchingrevenge reblogged this · 6 years ago

shes666searchingrevenge reblogged this · 6 years ago -

its5amandiamstillonduolingo reblogged this · 6 years ago

its5amandiamstillonduolingo reblogged this · 6 years ago -

allycat173 liked this · 6 years ago

allycat173 liked this · 6 years ago

A reblog of nerdy and quirky stuff that pique my interest.

291 posts