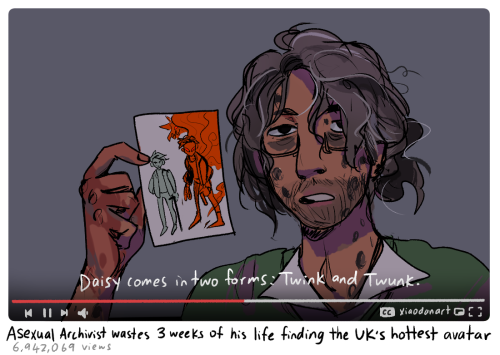

Went Digging Through The Old WIP Folder And Found This Idea I Never Got Around To Fully Realizing, Probably

went digging through the old WIP folder and found this idea I never got around to fully realizing, probably not gonna finish it but I still dig the vibe

More Posts from Pastaparty7 and Others

"KIM KITSURAGI – Detective, each of us has our part to play in the world. My part is to solve crimes. I am under no illusion that my role isn't a minor one, in the scheme of things... but I embrace it *because* it's my role, and it's yours too, detective, whether you accept it or not"

Tulips in Spring: a Magnus Archives Fanfic

Jon had thrown away godhood for him, like it hadn’t mattered.

Maybe it hadn’t.

Maybe Jon had just wanted the pain to end, and deification was something he had to step on to get there, like a stool to reach the top shelf.

Martin loved Jon. Jon loved him, and that meant they could fix this.

All Jon had to do was wake up.

Written for @seasons-in-the-archives' spring event. Takes place immediately after MAG 200.

AO3

------------------------

Cut the tether. Send them away.

He hadn’t thought he could.

Maybe we both die, but maybe not. Maybe everything works out, and we end up somewhere else.

One way or another, together. That was worth the risk.

Then he’d done the hard thing, the worst thing, the thing he’d warned himself he would have to do, and stabbed the one he loved.

The Web’s jury-rigged portal had taken them at once.

There’d been no time to process, no time to think, only to feel as they tore along the skein of pressure and speed, hurtled through the gaping wound between realities.

Martin hadn’t thought they’d wake up at all—never mind in some weird, brown field, three bodies under the moon.

Jon was bleeding, Jonah very dead, and Martin had not seen the tulips then.

It had been night, briskly cold under a star-choked sky. He had spotted a cabin and carried Jon there like he weighed nothing, shouting for help, bellowing himself into a hoarseness that would last for days.

The cabin was empty.

It was also unlocked, and Martin claimed it immediately as spoils of war.

#

There was power via solar panels. There was unlabeled canned food, and a… condition in the fridge of long-spoiled sustenance. None of that mattered.

The water ran clear and tasted fine, though it smelled of chlorine or something similar.

There was no phone. No television. No computer. That didn’t matter, either.

What mattered was the first aid kit under the bathroom sink.

Jon was alive, if unresponsive, and breathing sluggishly, but breathing, and his eyes were open and would not close, but they didn't move, so maybe he wasn’t seeing anything?

Was it like the apocalypse? Eyes open forever, not drying out, just spooky?

Didn’t matter.

The wound gaped like a mouth. Martin stitched, and cried, and thanked whatever goodness there was that he’d sewn so much in his teens.

Jon did not wake.

But he did not die, either.

#

Jon didn’t die.

And he didn’t die.

But Martin couldn’t get him to eat.

Maybe he still “ate” statements. Martin tried to recall ones he’d read before, but without the Eye’s power, he stumbled through them, forgot details, tripped over his own trailing thoughts.

It made no difference.

Jon didn’t die. After three days without infection, without things changing for the worse, without the Fears descending like ravenous wolves, Martin began to believe that Jon wouldn’t.

But he wouldn’t wake, either.

If only he’d wake up.

#

Martin was angry, after that.

The cabin sat in the center of a field, with only a distant blue line of hills to frame it.

He tripped over a handle in the backyard and so found the hidden door. Grass-covered, it opened with a hiss and ominous condensation.

Martin let it air out for a few hours before going in.

Face covered with a towel, he carried his anger down, and found enough supplies to keep them fed for years.

Longer, if Jon never ate again.

Worryingly, he also found packages labeled, RADIATION EXPOSURE: #1, #2, #3.

None were open. He did not open them. If they were going to die from radiation, it was probably already too late.

And maybe Martin wanted it to be.

Jon wouldn’t wake.

Jonah lay out in the field, rotting.

Martin had blood on his hands, and though he’d long washed it off, he could feel it there still.

He was angry.

Suddenly, it wasn’t enough that Jonah was peacefully moldering, getting away with everything again, and Martin grabbed an axe and a shovel from this underground storage and took his anger outside.

It was time to dig a pit. It was time to make a mess.

Why worry when you could just make a hole really deep and drop in the pieces?

Why worry when you could chop the man at fault as many times as you wanted, and there was no one around to tell you, that’s enough?

Jonah wouldn’t feel it, but Martin told himself maybe he would. Told himself he was glad Jon had stabbed him, and had stabbed him a lot. Told himself maybe Jonah would know, that Hell was real just for him, that some cultures had it right, and damaging Jonah’s body would damage whatever opportunities arose in the afterlife.

Or maybe this was all there was, and Jonah was released into the ether.

Either way, dismembering the son of a bitch felt good.

Maybe, he thought as gore slicked his hands, Gertrude’d had the right idea, all along.

#

Sometimes, Jon breathed too fast.

Sometimes, Jon groaned, face tight as he shuddered.

Martin held him those times, rocked him, and cried.

He pleaded. Begged Jon to come back, or tell him what to do.

There were no signs given. Nothing changed, and those times, Martin felt more helpless than he ever had.

#

A month, and no one had come.

How did it feel? Good? Terrifying?

Abandoned?

Martin could no longer tell.

He yelled, sometimes. Yelled at Jon, though it was pointless.

Cried at him, too.

He found schoolbooks in the underground bunker (because that’s what it was), blank notebooks, and graphite pencils.

Martin tried not to think about the child who would have used them, and claimed the notebooks for himself.

He wrote and he journaled, and during one of these sessions, he realized he’d forgiven Jon.

Forgiven Jon for breaking his promise, for abandoning the plan they’d devised (okay, the others had devised, and Jon had never liked).

Forgiven him for spurning the Spider’s solution, the one Martin wanted to hear: that there was a magic button to turn the apocalypse off, and it wouldn’t cost anything to use.

Right. In hindsight, Martin felt sick that he’d believed it so quickly.

“I forgive you,” he’d whispered to Jon, and he had: even for swallowing godhood like a cyanide tooth, and in doing so, leaving Martin alone.

He felt like he’d skipped a couple stages of grief and landed in acceptance.

He was depressed, Martin wrote, the graphite smudging his hand. He told me how bad he felt, and that he had no hope, and I didn’t listen because it hurt to think of him suffering like that.

Martin’s breath came stuttered, and he furiously wiped at his tears.

He told me how bad it was. He sheltered me from it, but he couldn’t save himself. I feel stupid. Of course he decided to end everything. I should’ve seen it coming.

It was weirdly gratifying to sit in that and let it hurt, like punishment.

What if he had seen it coming?

He couldn’t have shielded Jon from the terrors of the world.

He couldn’t have “fixed” Jon’s depression, because depression didn’t work that way.

But he could have listened. Accepted. Even if he hadn’t liked what was said.

Here, in this quiet cabin in an empty world, Martin could see that if he had let himself feel the horror that was Jon’s every living moment, he would have seen it coming and absolutely been able to stop what Jon did.

It was a sobering thought. A terrible thought. A thought that made Martin want to go out and dig Jonah up so he could chop his bones some more.

Martin cried.

When he went to wash his hands, he was startled to find he’d rubbed graphite all over his face.

He looked bruised.

Fittingly, the words he’d smudged had stained him.

“Oh, Jon,” he whispered. They’d both wrecked things pretty handily, hadn’t they?

But that didn’t mean it was over.

Martin crawled back into bed like he’d crawled through the burned-flesh hole in his heart, and knew he still loved Jon.

Martin knew Jon loved him, too.

Jon had thrown away godhood for him, like it hadn’t mattered.

Maybe it hadn’t.

Maybe Jon had just wanted the pain to end, and deification was something he had to step on to get there, like a stool to reach the top shelf.

Jon loved him, and that meant they could fix this.

They could still make this work.

All Jon had to do was wake.[1]

“I get it, Jon, all right?” said Martin. “I get it, and I’m sorry. Please wake up.”

Jon didn’t.

“What do you want me to do? I’ll do it. Anything.” Martin held him tightly, trying to find his warmth and heartbeat reassuring, and not just byproducts of eternal sleep.

Jon would wake up. He had to. He had to.

Maybe Martin hadn’t skipped denial, after all.

#

Nights were cold. Martin gave in and used the fireplace, which he’d been hesitant to do because there were no trees anywhere, and the only wood he’d found was already in the hearth.

It turned out his worry was unnecessary. The weird brass lighter sparked to life, and the wood caught—but did not burn.

The fire blazed indigo, like something out of a science experiment. It gave off no smoke, but produced a lovely heat.

The wood stayed intact. Absolutely wild.

Martin decided not to look a gift horse in the mouth. This world may have killed everyone in it, but at least they’d invented some nifty stuff before they died.

Stuff hadn’t saved them, though.

Martin tried not to think he and Jon wouldn’t make it, either. He would not think that.

He dared not.

Besides, he’d gotten used to unlabeled cans of savory mush, and his body digested it just fine. He was healthy. He was good.

Jon was healthy, too, if unconscious.

This was fine.

Jon would wake up any day now.

He must.

#

Spring came like a kiss, light and wet and sweet, and only when the fields began to bloom did Martin realize what all the brown things were.

Tulips.

This was clearly once a tended place, like Amsterdam, or something. The flowerbed stretched out from the front door in widening rows, as if the cabin had once spewed beauty.

He walked it; his best guess was three miles of flowers, and all were not, in fact, dead.

He was no gardener, and had no clue how long it had all lain fallow, but he figured he could give it a go.

After all, he knew by now that no one else was coming to do it.

There’d been no planes. Never a voice, or music. Not a motor, or smoke, or a distant, barking dog.

The bunker had tools, books on homesteading, and hermetically sealed seeds.

It also had bones.

He’d found them in the back. Three skeletons, each a little smaller than the other, like a family that had decided to lie down and die.

No flesh. No rot. No bugs. Whatever ended them had cleaned them well. He was grateful for that, at least.

Maybe this whole world really was dead.

It would explain why the Fears were so quiet.

He’d feltlonely the first weeks, but he’d been in full stage-two anger by then, and beat it back with rage and tantrums. It wasn’t the Lonely. It was just being alone.

Maybe the Fears were starving.

Or maybe they were all feeding off Jon, and he was trapped in an unending nightmare, unable to get free.

That thought made Martin afraid he was hurting him, keeping him alive. If maybe it would be kinder to…

Nope.

“You only have to stab your boyfriend once in your life, thank you very much,” he informed the tulip field. “I’ve already played that card.”

It was supposed to be funny, but it wasn’t, and Martin went back to the cabin and cried.

#

Martin buried the family’s bones in the flat, empty field. He didn’t know how else to thank them.

#

He spent a few precious days reading gardening books to Jon.

It felt like some kind of deal. He’d do this, coax the land back to life, and Jon would come back, too.

It didn’t really make sense, but neither did fire-baby messiahs or mannequins that talked, so who knew?

It couldn’t hurt to try.

#

Day after day, he trimmed old tulips, and dug up ones that were dead. Day after day, he cleared out space so the rows realigned, and transplanted the colors that bloomed in the wrong spot.

And day after day, he returned to Jon, and told him about the flowers, and about the poem he was writing. Then he bathed them both, ate some mush, and went to bed.

At least none of the cans were peaches.

Maybe he’d spent too much time in the Lonely to be right in the head, but… this wasn’t so bad.

Carrying Jon to the frankly enormous bathtub felt precious, like a rite. Kissing his scars, holding him in warm and bubbly water, felt like worship.

Sometimes, he sat in the tub with him.

He used the hot water to loosen Jon’s limbs so he could move them, bending his joints, lightly exercising his muscles. He’d learned to do that taking care of his mother, what felt like centuries ago. When Jon finally woke, after all, Martin wanted him well.

If Jon woke.

Often, in the bath, Martin told Jon how hard it was to be alone, and told him he was sorry.

Told him he forgave him for what he’d done.

Begged him to come back.

Jon still wouldn’t wake up.

#

The place he’d buried Jonah grew white tulips, and they were not in the correct row.

They were a cancerous blotch across yellow and red, startling like the scars Jon carried because of him.

Martin decided they’d stay: an ugly monument to the worst bastard he’d ever known.

#

Martin liked to brush Jon’s hair. “You’re not alone,” he told him as he worked the gray-black braid.

It had grown so damned fast; Martin had stopped trying to cut it, and instead just kept it neat, and his graying beard trimmed.

“Whatever’s hurting you in there, I’d chop that, too, if I could.” And he’d laughed. “I think you may have fallen in love with an axe-murderer.”

But if that were true, Jon was a knife-murderer, so it balanced out.

“Who are we, anymore?” Martin kissed Jon’s temple. “Doesn’t matter, I guess. I’m not leaving.”

And: “I’m never leaving you.”

And: “I won’t give up. I love you, Jon.”

Martin liked to believe that Jon’s breathing calmed when he said that, and the time between groans grew longer.

#

By week fourteen, springtime was barreling toward summer, and Martin was pleased with his work.

The tulips fanned out from the cabin in vibrant waves, and in an odd sense, he felt like he’d accomplished something for the first time in his life.

Maybe he had. Every job he’d had was for his mother, to do what he had to do. Every hobby had been hidden, done in secret and embarrassing when found out.

But he’d done this without shame, and he had done it well.

It was good.

He hadn’t taken any tulips inside. In his head, he’d pictured Jon waking, gasping out the window at the cultivated love-note Martin had made for him, but maybe… maybe that wasn’t going to happen.

It was okay, if it didn’t. It hurt; but Martin loved Jon. If this was the rest of their life together, then this was the rest of their life.

In sickness and in health, he thought, and decided to bring the tulips to him.

He cut quite a few. Yellow, for hope. Red, for love. Pink, for luck.

He was pretty sure he’d gotten the floriography wrong, but his personal apocalyptic Google wasn’t functioning at the moment, so he did the best he could.

He trimmed them, placed them in a vase he’d found under the kitchen sink, and brought them to the bedside.

“I saw a bee today,” he said, putting the vase by Jon’s head. “First one. You’d think there’d be more, wouldn’t you? But there aren’t a lot of bugs. That’s only the third one I’ve seen.”

Jon didn’t answer, but his breathing was deep and steady.

“I know, right? Poor Annabelle’s spiders have got to all be starved by now.” He leaned over and smoothed Jon’s hair out of his face.

Jon was beautiful, he thought, scars and all.

“Maybe they’ve all starved,” he said, voice cracking. “I mean, it’s not like you’ve got enough fear to keep them going all by yourself, right?”

Nothing.

Martin swallowed and put his hand over Jon’s—always warm, softer than Martin’s. “I wish you could smell them. They’re lovely. It’s a shame nobody’s around to share them with. By which I mean you, you know.”

Jon merely breathed.

“Please don’t be suffering, Jon.” As he had every night since the Scottish safe house, he got into the bed and pulled Jon against him. “Please don’t. I need you. Don’t you know I need you?”

It wasn’t the first time he’d wept over Jon, helpless in a bed.

Martin wiped his eyes. “You know what? I think you should smell them.” He sat up, holding Jon close, and lay Jon’s cheek on his shoulder. Then, he reached for the vase.

Faces together, he brought the tulips near, closed his eyes, and inhaled.

Beautiful. Sort of spicy; almost citrusy. “They’re like some kind of lemony cousin, right?” he murmured, planting a kiss on his head. “Really refreshing.”

“It’s because of the eucalyptol and ocimene,” Jon said, and Martin damn near dropped the vase.

“Jon!”

Jon’s eyes had closed. His brow had knit, and he was breathing too fast. “Martin?”

“Jon!” Martin tossed the vase back onto the nightstand so fast that water sloshed all over. He was breathing fast, too, which made it hard to reply. “Jon!”

“You’re real?” Jon’s peek was fearful, as if he thought Martin might sprout sharp teeth and bite him.

Martin tried to say something intelligent, and instead, burst into tears.

“You’re real,” said Jon, and then they were both crying, and kissing, and clutching as if to merge into one.

“You’re awake!” Martin sobbed. “How? What happened?”

“They’re gone,” whispered Jon, who was trembling and weak and weeping. “It worked. I held on. It’s over, Martin. It’s over,” and that would have to be explained, but what with the crying and the kissing, it would take a good long while.

At some point, they knocked over the tulips, and they both managed to laugh as Martin cleaned up the spill.

#

They sat on the porch, sharing a blanket, and watched the moon descend the sky.

“You heard me?” said Martin.

“I heard everything you said,” Jon repeated, head on Martin’s shoulder. “You have no idea. It kept me sane, what you said.”

“I didn’t say nice things,” said Martin.

“But you said you-things. You were saying them, not any… nightmare-version of you they produced to make me let go. I don’t know if I could’ve hung on if I hadn’t heard you. If you hadn’t kept talking. You saved me.”

Martin swallowed. “From what?”

A gentle breeze wafted flowery scent over them like a prayer, and they both paused to take it in.

“When you tried to cut the tether and we fell through, they were unmoored from the world, but they were still connected to me because I survived.” Jon swallowed. “So when we came here, I had a choice.”

Martin groaned. “Please don’t tell me you could’ve let them go, and you didn’t.”

“Yes,” said Jon. “Not that it would in any way make up for what I’ve done.”

“You self-righteous idiot,” said Martin with frustrated affection, and kissed the side of his head. “Why did you do that?”

“I had to, Martin. This world isn’t empty,” said Jon, which was a surprise.

“It’s not?”

“No—though most of this continent is. At least it’s been cleaned since their great war; their technology is much better than ours. That’s why you aren’t dying from radiation poisoning.”

Martin shuddered.

“I couldn’t let the Fears loose here, Martin. Not on these people. They’d been through enough. I had to hang on.”

“So they were feeding off you,” Martin whispered. “For weeks and weeks.”

“It took billions of people to keep them alive, and I wasn’t enough,” Jon said, low and dark. “They starved to death, and it hurt.”

“It hurt you too, Jon!”

“I had to make them die,” said Jon with a viciousness Martin had never heard before, and hoped Jonah had in his final, bastard moments.

“They’re really gone?”

“They’re really gone. The Web was the last. Tried to trick me into letting her free.”

Martin swallowed. “You didn’t, though.”

“A manipulative fear, let loose in a world that already survived nuclear apocalypse? Of course I didn’t let her go.” Jon paused. “She said ‘good luck’ at the end. Like Jonah did. But… I almost think she actually meant it.”

“Ugh. Jonah said ‘good luck?’ What the hell?”

“Had to get the last word,” Jon sighed. “White tulips are an apology, by the way. I don’t know if it means anything, but there you are.”

“Bastard man is not forgiven,” Martin said warmly, and kissed him, and Jon laughed, and it was a good and grateful moment.

The breeze moved, but that was all; no traffic. No construction. No voices.

This really wasn’t so bad.

“If we do decide to travel, it’ll take weeks,” said Jon, “so we’d need to go stocked. Not to worry—there’s an underground garage you didn’t find, with a solar-powered vehicle, so we wouldn’t have to go on foot.”

“Jon,” said Martin, wary. “You still know an awful lot of things, for the Eye being dead.”

“Past things,” said Jon, and smiled. “Now, I don’t. I won’t know names, or traumas, or whether anyone means us good or ill. I’ll know absolutely nothing without learning it the old-fashioned way.”

Did that mean Jon would finally need to eat? “I found seeds. We can plant them. We can grow food that isn’t mush. We could just… stay,” Martin suggested. “At least for a while.”

“You know what? We could.” And Jon didn’t sound disappointed at all.

“We could. We did our part, Jon. We don’t have to go anywhere.”

“Nobody knows who we are here,” whispered Jon. “Nobody’s coming after us, or trying to make us do things, or seeking revenge. We’re free.”

Martin laughed, a shaky, too-much sound. “We’re free.”

“We’re free.” Jon turned his face to Martin’s shoulder. “And I’m sorry.”

“I know. And we’ve got all the time we need to talk about that later,” said Martin, because the sting was gone, and such sweetness had taken its place. “I forgive you, you know. This is what I wanted, if I’m honest. Just… us.”

“Just us,” Jon whispered. “We’ve got a proper second chance. Like those flowers, practically resurrected.”

“A little hard work is all they needed.”

“They needed you.” Jon kissed him, lidded and lingering. “So do I.”

“Making me blush, Sims.”

“Not nearly enough, Blackwood.” Jon touched his cheek. “I love you.”

“I love you, too. Let’s stay out here a little longer? I’m afraid I’m going to wake up.”

Jon touched his lips. “This is real,” he said, and didn’t blink, and his eyes still weren’t fully human.

They were Jon’s eyes, though. That made them wonderful. Beloved, under the moon. (And Martin knew what his next poem was going to be about.)

Martin laughed again. “I can’t believe it. Everything worked out.”

“One way or another, together,” said Jon. “You didn’t give up on me. Thank you for not giving up on me.”

“That’s never, ever going to happen,” Martin swore, and sealed it with a kiss.

They stayed until the moon sank low, and the breeze promised warm days and clear skies, and when they finally went to bed, they both knew they’d sleep well.

-----------------

NOTES:

Written for the "Spring in the Archives" event, centered around the general themes of rebirth, healing, growth, and also new beginnings.

Rebirth, healing, growth - they both need these things, and I knew Martin needed some time alone to find them.

I think I can safely say he did.

This truly is a happily-ever-after

IT’S HIVE DAY BABY!!! Jane Prentiss gave her statement 9 effervescent years ago.

(It is also my birthday. Celebrating turning 16 by looking at worm woman image)

(click for better quality)

year three of me drawing jon and the admiral cuddling in tones of purple for jon sims and cats day

its for my mental health

[I.D.: digital illustration of jon sims and the admiral sleeping on georgie's couch, made in warm shades of blue and purple. jon is a skinny Black person with curly greying hair and circular scars on their face and neck. he has a bandage on his neck and bags under his eyes, and the clothes he's wearing are clearly too large. the admiral is a fluffy grey cat who is very happy to snuggle with jon as they take a nap. next to the couch there is a small table, and on it, an empty cup and a tape recorder. in the bottom right, the artist's signature: coelho. end I.D./]

-

climclem liked this · 3 weeks ago

climclem liked this · 3 weeks ago -

regrettably-the-main-blog liked this · 4 months ago

regrettably-the-main-blog liked this · 4 months ago -

goodkid-cinnamon reblogged this · 11 months ago

goodkid-cinnamon reblogged this · 11 months ago -

eclecticcosmonaut liked this · 1 year ago

eclecticcosmonaut liked this · 1 year ago -

seraphicrose reblogged this · 1 year ago

seraphicrose reblogged this · 1 year ago -

rittersporne liked this · 1 year ago

rittersporne liked this · 1 year ago -

ex-alias reblogged this · 1 year ago

ex-alias reblogged this · 1 year ago -

special-interest-mushroom liked this · 1 year ago

special-interest-mushroom liked this · 1 year ago -

lizard-spams-your-dash-too liked this · 1 year ago

lizard-spams-your-dash-too liked this · 1 year ago -

gwendolyn-of-loxley reblogged this · 1 year ago

gwendolyn-of-loxley reblogged this · 1 year ago -

gwendolyn-of-loxley liked this · 1 year ago

gwendolyn-of-loxley liked this · 1 year ago -

ex-alias liked this · 1 year ago

ex-alias liked this · 1 year ago -

philosophicallie liked this · 1 year ago

philosophicallie liked this · 1 year ago -

spursthatjinglejanglejingle reblogged this · 1 year ago

spursthatjinglejanglejingle reblogged this · 1 year ago -

mmiirage liked this · 1 year ago

mmiirage liked this · 1 year ago -

shinysheepeagle liked this · 1 year ago

shinysheepeagle liked this · 1 year ago -

cobaltrequiem liked this · 1 year ago

cobaltrequiem liked this · 1 year ago -

blessed-pineapple-cruncher liked this · 1 year ago

blessed-pineapple-cruncher liked this · 1 year ago -

trlvsn liked this · 1 year ago

trlvsn liked this · 1 year ago -

doodlecrumb liked this · 1 year ago

doodlecrumb liked this · 1 year ago -

lunarsanctuary reblogged this · 1 year ago

lunarsanctuary reblogged this · 1 year ago -

lepetitprincipito reblogged this · 1 year ago

lepetitprincipito reblogged this · 1 year ago -

spursthatjinglejanglejingle liked this · 1 year ago

spursthatjinglejanglejingle liked this · 1 year ago -

soggyspegit liked this · 1 year ago

soggyspegit liked this · 1 year ago -

serxei liked this · 1 year ago

serxei liked this · 1 year ago -

magicvion liked this · 1 year ago

magicvion liked this · 1 year ago -

shutupthepunx111 liked this · 1 year ago

shutupthepunx111 liked this · 1 year ago -

they-hear-the-music reblogged this · 1 year ago

they-hear-the-music reblogged this · 1 year ago -

riiiimssss liked this · 1 year ago

riiiimssss liked this · 1 year ago -

lykoshi reblogged this · 1 year ago

lykoshi reblogged this · 1 year ago -

charbes liked this · 1 year ago

charbes liked this · 1 year ago -

invention-of-god liked this · 1 year ago

invention-of-god liked this · 1 year ago -

carrotundaschtick liked this · 1 year ago

carrotundaschtick liked this · 1 year ago -

sooapiie reblogged this · 1 year ago

sooapiie reblogged this · 1 year ago -

theinklingofcats reblogged this · 1 year ago

theinklingofcats reblogged this · 1 year ago -

crayonpencil liked this · 1 year ago

crayonpencil liked this · 1 year ago -

they-hear-the-music liked this · 1 year ago

they-hear-the-music liked this · 1 year ago -

blogowner11485 liked this · 1 year ago

blogowner11485 liked this · 1 year ago -

mansccre liked this · 1 year ago

mansccre liked this · 1 year ago -

sailorque liked this · 1 year ago

sailorque liked this · 1 year ago -

misak1to liked this · 1 year ago

misak1to liked this · 1 year ago -

chiraldreamscape liked this · 1 year ago

chiraldreamscape liked this · 1 year ago -

p-e-a-r liked this · 1 year ago

p-e-a-r liked this · 1 year ago -

vagaryvigilante reblogged this · 1 year ago

vagaryvigilante reblogged this · 1 year ago -

vagaryvigilante liked this · 1 year ago

vagaryvigilante liked this · 1 year ago -

normal-prommy reblogged this · 1 year ago

normal-prommy reblogged this · 1 year ago -

gay-people-exist liked this · 1 year ago

gay-people-exist liked this · 1 year ago -

jimboakimbo reblogged this · 1 year ago

jimboakimbo reblogged this · 1 year ago

Header by Peachymatsu on deviantart. Pfp is from the TGCF manhua (StarEmber)

157 posts