Your Level Of Education Means Nothing If You Never Learned Any Compassion

your level of education means nothing if you never learned any compassion

More Posts from Milk-tea-no-sugar and Others

Writing Prompt #1200

“Oh, um, that’s an incredibly polite offer, but I don’t particularly think my girlfriend would want me going on a date with someone we don’t know.”

“Oh, I’m so sorry, I didn’t realize that you were—”

“We can put a rain check on it, if you’d like to meet her. We’re always open to getting to know someone new.”

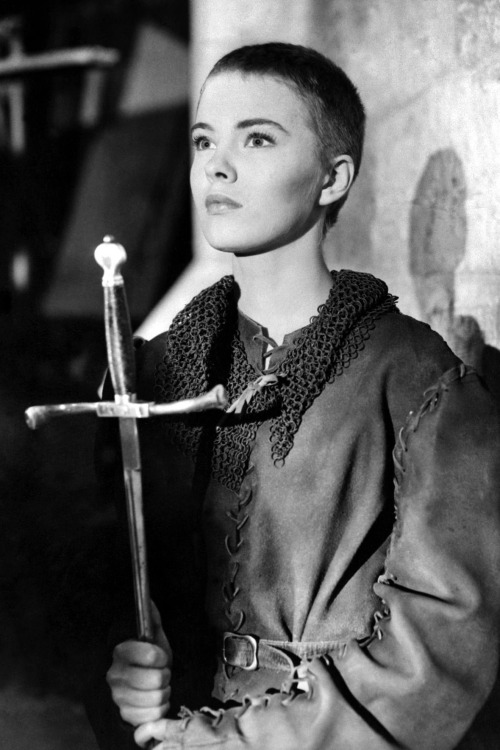

stage and film portrayals of joan of arc

condola rashad (saint joan, 2018) / renée jeanne falconetti (the passion of joan of arc, 1928) / jean seberg (saint joan, 1957) / ingrid bergman (joan of arc, 1948) / milla jovovich (the story of joan of arc, 1999) / diana sands (saint joan, 1967)

some important advice

did they just completely forget the word “with” or was this really how it was intended

English is weird

John McWhorter, The Week, December 20, 2015

English speakers know that their language is odd. So do nonspeakers saddled with learning it. The oddity that we all perceive most readily is its spelling, which is indeed a nightmare. In countries where English isn’t spoken, there is no such thing as a spelling bee. For a normal language, spelling at least pretends a basic correspondence to the way people pronounce the words. But English is not normal.

Even in its spoken form, English is weird. It’s weird in ways that are easy to miss, especially since Anglophones in the United States and Britain are not exactly rabid to learn other languages. Our monolingual tendency leaves us like the proverbial fish not knowing that it is wet. Our language feels “normal” only until you get a sense of what normal really is.

There is no other language, for example, that is close enough to English that we can get about half of what people are saying without training and the rest with only modest effort. German and Dutch are like that, as are Spanish and Portuguese, or Thai and Lao. The closest an Anglophone can get is with the obscure Northern European language called Frisian. If you know that tsiis is cheese and Frysk is Frisian, then it isn’t hard to figure out what this means: Brea, bûter, en griene tsiis is goed Ingelsk en goed Frysk. But that sentence is a cooked one, and overall, we tend to find Frisian more like German, which it is.

We think it’s a nuisance that so many European languages assign gender to nouns for no reason, with French having female moons and male boats and such. But actually, it’s we who are odd: Almost all European languages belong to one family–Indo-European–and of all of them, English is the only one that doesn’t assign genders.

More weirdness? OK. There is exactly one language on Earth whose present tense requires a special ending only in the third-person singular. I’m writing in it. I talk, you talk, he/she talks–why? The present-tense verbs of a normal language have either no endings or a bunch of different ones (Spanish: hablo, hablas, habla). And try naming another language where you have to slip do into sentences to negate or question something. Do you find that difficult?

Why is our language so eccentric? Just what is this thing we’re speaking, and what happened to make it this way?

English started out as, essentially, a kind of German. Old English is so unlike the modern version that it’s a stretch to think of them as the same language. Hwæt, we gardena in geardagum þeodcyninga þrym gefrunon–does that really mean “So, we Spear-Danes have heard of the tribe-kings’ glory in days of yore”? Icelanders can still read similar stories written in the Old Norse ancestor of their language 1,000 years ago, and yet, to the untrained English-speaker’s eye, Beowulf might as well be in Turkish.

The first thing that got us from there to here was the fact that when the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes (and also Frisians) brought Germanic speech to England, the island was already inhabited by people who spoke Celtic languages–today represented by Welsh and Irish, and Breton across the Channel in France. The Celts were subjugated but survived, and since there were only about 250,000 Germanic invaders, very quickly most of the people speaking Old English were Celts.

Crucially, their own Celtic was quite unlike English. For one thing, the verb came first (came first the verb). Also, they had an odd construction with the verb do: They used it to form a question, to make a sentence negative, and even just as a kind of seasoning before any verb. Do you walk? I do not walk. I do walk. That looks familiar now because the Celts started doing it in their rendition of English. But before that, such sentences would have seemed bizarre to an English speaker–as they would today in just about any language other than our own and the surviving Celtic ones.

At this date there is no documented language on Earth beyond Celtic and English that uses do in just this way. Thus English’s weirdness began with its transformation in the mouths of people more at home with vastly different tongues. We’re still talking like them, and in ways we’d never think of. When saying “eeny, meeny, miny, moe,” have you ever felt like you were kind of counting? Well, you are–in Celtic numbers, chewed up over time but recognizably descended from the ones rural Britishers used when counting animals and playing games. “Hickory, dickory, dock”–what in the world do those words mean? Well, here’s a clue: hovera, dovera, dick were eight, nine, and ten in that same Celtic counting list.

The second thing that happened was that yet more Germanic-speakers came across the sea meaning business. This wave began in the 9th century, and this time the invaders were speaking another Germanic offshoot, Old Norse. But they didn’t impose their language. Instead, they married local women and switched to English. However, they were adults and, as a rule, adults don’t pick up new languages easily, especially not in oral societies. There was no such thing as school, and no media. Learning a new language meant listening hard and trying your best.

As long as the invaders got their meaning across, that was fine. But you can do that with a highly approximate rendition of a language–the legibility of the Frisian sentence you just read proves as much. So the Scandinavians did more or less what we would expect: They spoke bad Old English. Their kids heard as much of that as they did real Old English. Life went on, and pretty soon their bad Old English was real English, and here we are today: The Norse made English easier.

I should make a qualification here. In linguistics circles it’s risky to call one language easier than another one. But some languages plainly jangle with more bells and whistles than others. If someone were told he had a year to get as good at either Russian or Hebrew as possible, and would lose a fingernail for every mistake he made during a three-minute test of his competence, only the masochist would choose Russian–unless he already happened to speak a language related to it. In that sense, English is “easier” than other Germanic languages, and it’s because of those Vikings.

Old English had the crazy genders we would expect of a good European language–but the Scandinavians didn’t bother with those, and so now we have none. What’s more, the Vikings mastered only that one shred of a once lovely conjugation system: Hence the lonely third-person singular -s, hanging on like a dead bug on a windshield. Here and in other ways, they smoothed out the hard stuff.

They also left their mark on English grammar. Blissfully, it is becoming rare to be taught that it is wrong to say Which town do you come from?–ending with the preposition instead of laboriously squeezing it before the wh-word to make From which town do you come? In English, sentences with “dangling prepositions” are perfectly natural and clear and harm no one. Yet there is a wet-fish issue with them, too: Normal languages don’t dangle prepositions in this way. Every now and then a language allows it: an indigenous one in Mexico, another in Liberia. But that’s it. Overall, it’s an oddity. Yet, wouldn’t you know, it’s a construction that Old Norse also happened to permit (and that modern Danish retains).

We can display all these bizarre Norse influences in a single sentence. Say That’s the man you walk in with, and it’s odd because (1) the has no specifically masculine form to match man, (2) there’s no ending on walk, and (3) you don’t say in with whom you walk. All that strangeness is because of what Scandinavian Vikings did to good old English back in the day.

Finally, as if all this weren’t enough, English got hit by a fire-hose spray of words from yet more languages. After the Norse came the French. The Normans–descended from the same Vikings, as it happens–conquered England and ruled for several centuries, and before long, English had picked up 10,000 new words. Then, starting in the 16th century, educated Anglophones began to develop English as a vehicle for sophisticated writing, and it became fashionable to cherry-pick words from Latin to lend the language a more elevated tone.

It was thanks to this influx from French and Latin (it’s often hard to tell which was the original source of a given word) that English acquired the likes of crucified, fundamental, definition, and conclusion. These words feel sufficiently English to us today, but when they were new, many persons of letters in the 1500s (and beyond) considered them irritatingly pretentious and intrusive, as indeed they would have found the phrase “irritatingly pretentious and intrusive.” There were even writerly sorts who proposed native English replacements for those lofty Latinates, and it’s hard not to yearn for some of these: In place of crucified, fundamental, definition, and conclusion, how about crossed, groundwrought, saywhat, and endsay?

But language tends not to do what we want it to. The die was cast: English had thousands of new words competing with native English words for the same things. One result was triplets allowing us to express ideas with varying degrees of formality. Help is English, aid is French, assist is Latin. Or, kingly is English, royal is French, regal is Latin–note how one imagines posture improving with each level: Kingly sounds almost mocking, regal is straight-backed like a throne, royal is somewhere in the middle, a worthy but fallible monarch.

Then there are doublets, less dramatic than triplets but fun nevertheless, such as the English/French pairs begin/commence and want/desire. Especially noteworthy here are the culinary transformations: We kill a cow or a pig (English) to yield beef or pork (French). Why? Well, generally in Norman England, English-speaking laborers did the slaughtering for moneyed French speakers at the table. The different ways of referring to meat depended on one’s place in the scheme of things, and those class distinctions have carried down to us in discreet form today.

The multiple influxes of foreign vocabulary partly explain the striking fact that English words can trace to so many different sources–often several within the same sentence. The very idea of etymology being a polyglot smorgasbord, each word a fascinating story of migration and exchange, seems everyday to us. But the roots of a great many languages are much duller. The typical word comes from, well, an earlier version of that same word and there it is. The study of etymology holds little interest for, say, Arabic speakers.

To be fair, mongrel vocabularies are hardly uncommon worldwide, but English’s hybridity is high on the scale compared with most European languages. The previous sentence, for example, is a riot of words from Old English, Old Norse, French, and Latin. Greek is another element: In an alternate universe, we would call photographs “lightwriting.”

Because of this fire-hose spray, we English speakers also have to contend with two different ways of accenting words. Clip on a suffix to the word wonder, and you get wonderful. But–clip an ending to the word modern and the ending pulls the accent along with it: MO-dern, but mo-DERN-ity, not MO-dern-ity. That doesn’t happen with WON-der and WON-der-ful, or CHEER-y and CHEER-i-ly. But it does happen with PER-sonal, person-AL-ity.

What’s the difference? It’s that -ful and -ly are Germanic endings, while -ity came in with French. French and Latin endings pull the accent closer–TEM-pest, tem-PEST-uous–while Germanic ones leave the accent alone. One never notices such a thing, but it’s one way this “simple” language is actually not so.

Thus English is indeed an odd language, and its spelling is only the beginning of it. What English does have on other tongues is that it is deeply peculiar in the structural sense. And it became peculiar because of the slings and arrows–as well as caprices–of outrageous history.

-

uzupiss liked this · 1 month ago

uzupiss liked this · 1 month ago -

actualnerdtrash liked this · 1 month ago

actualnerdtrash liked this · 1 month ago -

strawberrytendou liked this · 1 month ago

strawberrytendou liked this · 1 month ago -

chemicaltreachery reblogged this · 1 month ago

chemicaltreachery reblogged this · 1 month ago -

theblue-princess reblogged this · 1 month ago

theblue-princess reblogged this · 1 month ago -

brandylolz reblogged this · 1 month ago

brandylolz reblogged this · 1 month ago -

deathandbutterflies reblogged this · 1 month ago

deathandbutterflies reblogged this · 1 month ago -

deathandbutterflies liked this · 1 month ago

deathandbutterflies liked this · 1 month ago -

voldey reblogged this · 1 month ago

voldey reblogged this · 1 month ago -

3amchild reblogged this · 1 month ago

3amchild reblogged this · 1 month ago -

crystalclrs liked this · 1 month ago

crystalclrs liked this · 1 month ago -

consulsmirror reblogged this · 1 month ago

consulsmirror reblogged this · 1 month ago -

vandiste liked this · 1 month ago

vandiste liked this · 1 month ago -

suicidollz reblogged this · 1 month ago

suicidollz reblogged this · 1 month ago -

suicidollz liked this · 1 month ago

suicidollz liked this · 1 month ago -

aunty-tiger-potato reblogged this · 1 month ago

aunty-tiger-potato reblogged this · 1 month ago -

uhave-ctrl reblogged this · 1 month ago

uhave-ctrl reblogged this · 1 month ago -

uhave-ctrl liked this · 1 month ago

uhave-ctrl liked this · 1 month ago -

8teenndream liked this · 1 month ago

8teenndream liked this · 1 month ago -

kuviras-eyeliner reblogged this · 1 month ago

kuviras-eyeliner reblogged this · 1 month ago -

kuviras-eyeliner liked this · 1 month ago

kuviras-eyeliner liked this · 1 month ago -

sakurabakugo liked this · 1 month ago

sakurabakugo liked this · 1 month ago -

serenitycushing liked this · 1 month ago

serenitycushing liked this · 1 month ago -

inumaki-toge-senpai liked this · 1 month ago

inumaki-toge-senpai liked this · 1 month ago -

rikeza liked this · 1 month ago

rikeza liked this · 1 month ago -

rikeza reblogged this · 1 month ago

rikeza reblogged this · 1 month ago -

efflorescing-mary liked this · 1 month ago

efflorescing-mary liked this · 1 month ago -

gojosato liked this · 1 month ago

gojosato liked this · 1 month ago -

livelaughlovenavia liked this · 1 month ago

livelaughlovenavia liked this · 1 month ago -

lightningnose reblogged this · 1 month ago

lightningnose reblogged this · 1 month ago -

existing-apparently liked this · 1 month ago

existing-apparently liked this · 1 month ago -

scrawled-in-ink liked this · 1 month ago

scrawled-in-ink liked this · 1 month ago -

oceanwoozi reblogged this · 1 month ago

oceanwoozi reblogged this · 1 month ago -

ashookykooky reblogged this · 1 month ago

ashookykooky reblogged this · 1 month ago -

ashookykooky liked this · 1 month ago

ashookykooky liked this · 1 month ago -

milk-violet liked this · 1 month ago

milk-violet liked this · 1 month ago -

liberhoe reblogged this · 1 month ago

liberhoe reblogged this · 1 month ago -

beingsuneone reblogged this · 1 month ago

beingsuneone reblogged this · 1 month ago -

liberhoe liked this · 1 month ago

liberhoe liked this · 1 month ago -

beingsuneone liked this · 1 month ago

beingsuneone liked this · 1 month ago -

strxnged reblogged this · 1 month ago

strxnged reblogged this · 1 month ago -

strxnged liked this · 1 month ago

strxnged liked this · 1 month ago -

andromeda-nova-writing reblogged this · 1 month ago

andromeda-nova-writing reblogged this · 1 month ago -

milkstore reblogged this · 1 month ago

milkstore reblogged this · 1 month ago -

realjonahofficial liked this · 1 month ago

realjonahofficial liked this · 1 month ago -

naefelldaurk reblogged this · 1 month ago

naefelldaurk reblogged this · 1 month ago -

naefelldaurk liked this · 1 month ago

naefelldaurk liked this · 1 month ago -

freshsunberries liked this · 1 month ago

freshsunberries liked this · 1 month ago -

shibarakudesu liked this · 1 month ago

shibarakudesu liked this · 1 month ago -

shalem-things reblogged this · 1 month ago

shalem-things reblogged this · 1 month ago