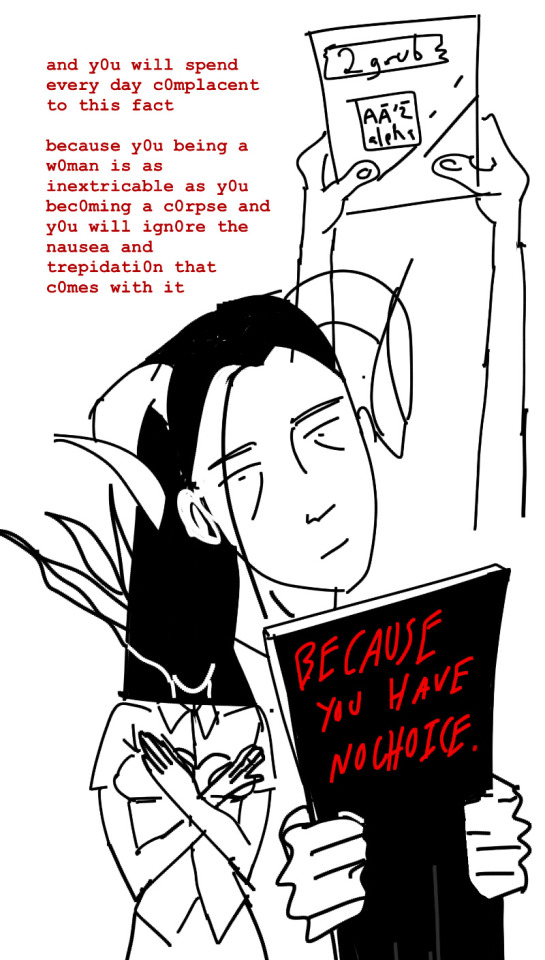

Aradia Gender Meta Post : 1/2 ( Part 2 Is In The Reblogs! )

Aradia gender meta post : 1/2 ( part 2 is in the reblogs! )

More Posts from Manosuavez and Others

"I think Homer outwits most writers who have written on the War [fantasy archetype], by not taking sides.

The Trojan war is not and you cannot make it be the War of Good vs. Evil. It’s just a war, a wasteful, useless, needless, stupid, protracted, cruel mess full of individual acts of courage, cowardice, nobility, betrayal, limb-hacking-off, and disembowelment. Homer was a Greek and might have been partial to the Greek side, but he had a sense of justice or balance that seems characteristically Greek — maybe his people learned a good deal of it from him? His impartiality is far from dispassionate; the story is a torrent of passionate actions, generous, despicable, magnificent, trivial. But it is unprejudiced. It isn’t Satan vs. Angels. It isn’t Holy Warriors vs. Infidels. It isn’t hobbits vs. orcs. It’s just people vs. people.

Of course you can take sides, and almost everybody does. I try not to, but it’s no use; I just like the Trojans better than the Greeks. But Homer truly doesn’t take sides, and so he permits the story to be tragic. By tragedy, mind and soul are grieved, enlarged, and exalted.

Whether war itself can rise to tragedy, can enlarge and exalt the soul, I leave to those who have been more immediately part of a war than I have. I think some believe that it can, and might say that the opportunity for heroism and tragedy justifies war. I don’t know; all I know is what a poem about a war can do. In any case, war is something human beings do and show no signs of stopping doing, and so it may be less important to condemn it or to justify it than to be able to perceive it as tragic.

But once you take sides, you have lost that ability.

Is it our dominant religion that makes us want war to be between the good guys and the bad guys?

In the War of Good vs. Evil there can be divine or supernal justice but not human tragedy. It is by definition, technically, comic (as in The Divine Comedy): the good guys win. It has a happy ending. If the bad guys beat the good guys, unhappy ending, that’s mere reversal, flip side of the same coin. The author is not impartial. Dystopia is not tragedy.

Milton, a Christian, had to take sides, and couldn’t avoid comedy. He could approach tragedy only by making Evil, in the person of Lucifer, grand, heroic, and even sympathetic — which is faking it. He faked it very well.

Maybe it’s not only Christian habits of thought but the difficulty we all have in growing up that makes us insist justice must favor the good.

After all, 'Let the best man win' doesn’t mean the good man will win. It means, 'This will be a fair fight, no prejudice, no interference — so the best fighter will win it.' If the treacherous bully fairly defeats the nice guy, the treacherous bully is declared champion. This is justice. But it’s the kind of justice that children can’t bear. They rage against it. It’s not fair!

But if children never learn to bear it, they can’t go on to learn that a victory or a defeat in battle, or in any competition other than a purely moral one (whatever that might be), has nothing to do with who is morally better.

Might does not make right — right?

Therefore right does not make might. Right?

But we want it to. 'My strength is as the strength of ten because my heart is pure.'

If we insist that in the real world the ultimate victor must be the good guy, we’ve sacrificed right to might. (That’s what History does after most wars, when it applauds the victors for their superior virtue as well as their superior firepower.) If we falsify the terms of the competition, handicapping it, so that the good guys may lose the battle but always win the war, we’ve left the real world, we’re in fantasy land — wishful thinking country.

Homer didn’t do wishful thinking.

Homer’s Achilles is a disobedient officer, a sulky, self-pitying teenager who gets his nose out of joint and won’t fight for his own side. A sign that Achilles might grow up someday, if given time, is his love for his friend Patroclus. But his big snit is over a girl he was given to rape but has to give back to his superior officer, which to me rather dims the love story. To me Achilles is not a good guy. But he is a good warrior, a great fighter — even better than the Trojan prime warrior, Hector. Hector is a good guy on any terms — kind husband, kind father, responsible on all counts — a mensch. But right does not make might. Achilles kills him.

The famous Helen plays a quite small part in The Iliad. Because I know that she’ll come through the whole war with not a hair in her blond blow-dry out of place, I see her as opportunistic, immoral, emotionally about as deep as a cookie sheet. But if I believed that the good guys win, that the reward goes to the virtuous, I’d have to see her as an innocent beauty wronged by Fate and saved by the Greeks.

And people do see her that way. Homer lets us each make our own Helen; and so she is immortal.

I don’t know if such nobility of mind (in the sense of the impartial 'noble' gases) is possible to a modern writer of fantasy. Since we have worked so hard to separate History from Fiction, our fantasies are dire warnings, or mere nightmares, or else they are wish fulfillments."

- Ursula K. Le Guin, from No Time to Spare, 2013.

im laughing so hard because no matter what song you listen to

spiderman dances to the beat

no matter what song ive been testing it and lauing my ass off for an hour

it is quite frankly baffling to me that pippin isn’t universally regarded to be one of the best musicals of all time... imagine you’re a musical. you’ve got it all: solely bangers on the soundtrack (simple joys! on the right track! extraordinary!). you’ve got identity crises (many). you’ve got sex. you’ve got patricide. you’ve got LAYERS OF PERFORMANCE — the actors are playing actors who are playing the characters and yes of course all of that is important. you’ve got a protagonist who is borderline insufferable for a lot of the show and is almost always being given terrible advice by the other characters. there’s a SING-ALONG portion in most productions! you, as a show, are using and fucking with the medium of theatre to such a degree that by the time the audience reach the finale everything is so tangled that they might not fully understand it and how unsettling it is until they look back and it hits them and they have to sit down for a while. and still nobody else in my life cares about you? ….😔 how come?

dave meets the queen

this is one is important as fuck i see so many people not understand this and it drives me crazy

"Sburb ruins, mythic challenges, and personal quests generally tend to come off as shallow busywork, stage props, or set pieces in a spurious Hero's Journey. Rose either faintly glimpses this truth at this early stage, or she's just hitting her rebellious teen stride. Either way, she doesn't take the surface value of the quest seriously at all, and only wants to smash it apart and loot the secrets. My sense is that the average reader reacts to this impulse unfavorably. Because readers watch the formula play out so often, they are trained heavily to respect the journey of the hero, to anticipate and crave its fulfillment, to see it as something verging on contractual in their relationship with a story. So a gut-response to this recklessness is like, "ROSE, NO! STOP THAT! You simply must complete your quest and play the rain!" What comes with this view is the feeling that her evolution as a character is only being delayed for a bit while she gets some anti-narrative foolishness out of her system, and then we'll get down to business and watch her do her quest, play a whole BUNCH of rain, and reap the narrative satisfaction. There's just one problem: she never does that. This candy-coated Kiddie Kwest is at no point ever taken seriously by Rose or the narrative itself, nor should it be.

When trying to parse character arcs, we look out for certain beacons. So when we hear "play the rain," we're like, ah, GOT IT. That's Rose's arc. Once she finally gets over this destructive teen bullshit, she can wise up, play the rain, and her arc will be finished. Wrong. This is almost a red herring arc. Her quest on this planet, its patronizing presentation, its intrinsic shallowness, is a mirage surrounding her that represents a fully regimented series of milestones for achievement and personal growth, much as society dubiously presents to young people in many forms. The true arc-within-the-arc is actually an upside-down version of what it appears to be. What Rose is doing now, which seems to be misguided recklessness taking her further away from the truth of herself, is actually better seen as a good start to her real journey: breaching the mirage of regimented growth, exposing it for the charade it is, and pulling the truth out of it. The real conflict in her arc comes not from the fact that she refuses to take it seriously, by destroying it and taking shortcuts. It's the opposite. It's that, upon trashing her planet, she continues to have this nagging sense that she should be taking this quest seriously, much like how a young adult may have a nagging sense of guilt that they aren't "being an adult right" by the time they approach adulthood. And this nagging, unanswerable guilt arises from the truth that the regimentation of adulthood is completely fake. It was always a mirage. Learning this, making peace with it, is part of the growing process for many, and it is for her too." -Andrew Hussie

intrinsically queer as fuck, too, btw

if no one else got me I know I can’t stop the loneliness by anri got me

the Heir is a hero who reviles what he reveres. an Heir in fairy tales is one who wants nothing more than to attain his father’s station, but hates his father for not giving it to him; or one who loves the privileges of his rank but hates its responsibilities, wishing for the freedom of a commoner.

Equius wants to be dominated by what he hates, and loves what is beneath him when he should be exercising dominance over it. he hates meat - implying to Nepeta that he doesn’t eat it - but values his own “meat” or flesh over his spirit. Alternia’s indigo caste - its Heir class - is entirely a caste of walking contradictions. they treat the planet’s musclebeasts as creatures “meant to be 100ked upon with adoration“, but treat another race of man-beasts as inferior, fit only for the role of being part of a “butler genus”. though they exist to serve those above them, they reject the sea dwellers for being “EVEN PURPLIER“ than the subjugglators, in fact considering themselves “obligated to be at odds”. it’s only fitting that Equius is the one to discuss the difference between friends and enemies with his superior only a page after we’re told that “in troll language, the word for friend is exactly the same as the word for enemy.”

naturally this makes the Heir a class closely tied with the concept of masculinity, because the complex dual nature of masculinity is such a strong theme in Homestuck. the indigoblood’s power comes not just from his position on the hemospectrum but his position in a patriarchal society, and when Equius starts to lose his grip on the saddle of his high horse it’s not only for a lowblood, but for a lowblooded woman.

the successful Heir is a hero who successfully overcomes masculinity’s trappings and, like all heroes ultimately must, reconciles the contradicting aspects of the masculine and the feminine. John matures as an Heir by overcoming the side effects of being brought up in an all male household, under a father who valued his strength of the flesh above all else, and mastering the spirit and the feminine - represented by spirit arms and the feminine blue slime of his ghostly mentor. Equius’ fate is instead to succumb to masculinity altogether, allowing the male superior in his life to cut off his connection to breath entirely.

Plein air from yesterday

Hector and Helenus' potential dynamic is so funny to me

#ally

fag

-

sauceconsumer reblogged this · 1 week ago

sauceconsumer reblogged this · 1 week ago -

egomassacre liked this · 1 week ago

egomassacre liked this · 1 week ago -

airburned liked this · 2 weeks ago

airburned liked this · 2 weeks ago -

airburned reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

airburned reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

arawrdia reblogged this · 2 weeks ago

arawrdia reblogged this · 2 weeks ago -

buhbo liked this · 1 month ago

buhbo liked this · 1 month ago -

vinylyuri reblogged this · 1 month ago

vinylyuri reblogged this · 1 month ago -

rondomon reblogged this · 1 month ago

rondomon reblogged this · 1 month ago -

rondomon reblogged this · 1 month ago

rondomon reblogged this · 1 month ago -

lonelyhum liked this · 1 month ago

lonelyhum liked this · 1 month ago -

coryptid liked this · 1 month ago

coryptid liked this · 1 month ago -

pimbo liked this · 1 month ago

pimbo liked this · 1 month ago -

jackalopegothic reblogged this · 1 month ago

jackalopegothic reblogged this · 1 month ago -

jackalopegothic liked this · 1 month ago

jackalopegothic liked this · 1 month ago -

antediluvianapocalypse reblogged this · 1 month ago

antediluvianapocalypse reblogged this · 1 month ago -

ghwoulies liked this · 1 month ago

ghwoulies liked this · 1 month ago -

aggrivatinggrimalkin liked this · 1 month ago

aggrivatinggrimalkin liked this · 1 month ago -

botanical-shitpost-machine liked this · 1 month ago

botanical-shitpost-machine liked this · 1 month ago -

vriskca reblogged this · 1 month ago

vriskca reblogged this · 1 month ago -

zoeytheariesqueen liked this · 2 months ago

zoeytheariesqueen liked this · 2 months ago -

gnawdar reblogged this · 2 months ago

gnawdar reblogged this · 2 months ago -

gnawdar liked this · 2 months ago

gnawdar liked this · 2 months ago -

fall1ngfeather reblogged this · 2 months ago

fall1ngfeather reblogged this · 2 months ago -

mitsurami liked this · 2 months ago

mitsurami liked this · 2 months ago -

meow-nepeta reblogged this · 2 months ago

meow-nepeta reblogged this · 2 months ago -

unionize-catgirls liked this · 2 months ago

unionize-catgirls liked this · 2 months ago -

miiicrobat reblogged this · 2 months ago

miiicrobat reblogged this · 2 months ago -

miiicrobat liked this · 2 months ago

miiicrobat liked this · 2 months ago -

paladinofheart liked this · 2 months ago

paladinofheart liked this · 2 months ago -

socialmediasochist reblogged this · 2 months ago

socialmediasochist reblogged this · 2 months ago -

insaneoddball reblogged this · 2 months ago

insaneoddball reblogged this · 2 months ago -

insaneoddball liked this · 2 months ago

insaneoddball liked this · 2 months ago -

pubby-pupperoni liked this · 2 months ago

pubby-pupperoni liked this · 2 months ago -

oddpocalypse reblogged this · 2 months ago

oddpocalypse reblogged this · 2 months ago -

oddpocalypse liked this · 2 months ago

oddpocalypse liked this · 2 months ago -

whichcaptainjack reblogged this · 2 months ago

whichcaptainjack reblogged this · 2 months ago -

softwaluigi liked this · 2 months ago

softwaluigi liked this · 2 months ago -

cuntylilcal reblogged this · 2 months ago

cuntylilcal reblogged this · 2 months ago -

cuntylilcal liked this · 2 months ago

cuntylilcal liked this · 2 months ago -

socialstudyque liked this · 2 months ago

socialstudyque liked this · 2 months ago -

pezuzi liked this · 2 months ago

pezuzi liked this · 2 months ago -

bitronic liked this · 2 months ago

bitronic liked this · 2 months ago -

skenpiel liked this · 2 months ago

skenpiel liked this · 2 months ago -

dongoverlord reblogged this · 2 months ago

dongoverlord reblogged this · 2 months ago -

sypherixus reblogged this · 2 months ago

sypherixus reblogged this · 2 months ago -

sypherixus liked this · 2 months ago

sypherixus liked this · 2 months ago -

dongoverlord liked this · 2 months ago

dongoverlord liked this · 2 months ago -

honkooop liked this · 2 months ago

honkooop liked this · 2 months ago -

t4tbro liked this · 2 months ago

t4tbro liked this · 2 months ago -

meto4 reblogged this · 2 months ago

meto4 reblogged this · 2 months ago