North American Nebula Js

North American Nebula js

More Posts from Littlecadet-biguniverse and Others

Andromeda glowing in infrared.

Helix Nebula in Visible and in Infrared Light

The Helix Nebula, also known as NGC 7293, is a large planetary nebula (PN) located in the constellation Aquarius. Planetary nebulae like the Helix are sculpted late in a Sun-like star’s life by a torrential gush of gases escaping from the dying star. They have nothing to do with planet formation, but got their name because they look like planetary disks when viewed through a small telescope.

Credit: ESO/VISTA/J. Emerson.

Jupiter’s North Pole Unlike Anything Encountered in Solar System

NASA’s Juno spacecraft has sent back the first-ever images of Jupiter’s north pole, taken during the spacecraft’s first flyby of the planet with its instruments switched on. The images show storm systems and weather activity unlike anything previously seen on any of our solar system’s gas-giant planets.

Juno successfully executed the first of 36 orbital flybys on Aug. 27 when the spacecraft came about 2,500 miles (4,200 kilometers) above Jupiter’s swirling clouds. The download of six megabytes of data collected during the six-hour transit, from above Jupiter’s north pole to below its south pole, took one-and-a-half days. While analysis of this first data collection is ongoing, some unique discoveries have already made themselves visible.

“First glimpse of Jupiter’s north pole, and it looks like nothing we have seen or imagined before,” said Scott Bolton, principal investigator of Juno from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. “It’s bluer in color up there than other parts of the planet, and there are a lot of storms. There is no sign of the latitudinal bands or zone and belts that we are used to – this image is hardly recognizable as Jupiter. We’re seeing signs that the clouds have shadows, possibly indicating that the clouds are at a higher altitude than other features.”

One of the most notable findings of these first-ever pictures of Jupiter’s north and south poles is something that the JunoCam imager did not see.

“Saturn has a hexagon at the north pole,” said Bolton. “There is nothing on Jupiter that anywhere near resembles that. The largest planet in our solar system is truly unique. We have 36 more flybys to study just how unique it really is.”

Along with JunoCam snapping pictures during the flyby, all eight of Juno’s science instruments were energized and collecting data. The Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JI-RAM), supplied by the Italian Space Agency, acquired some remarkable images of Jupiter at its north and south polar regions in infrared wavelengths.

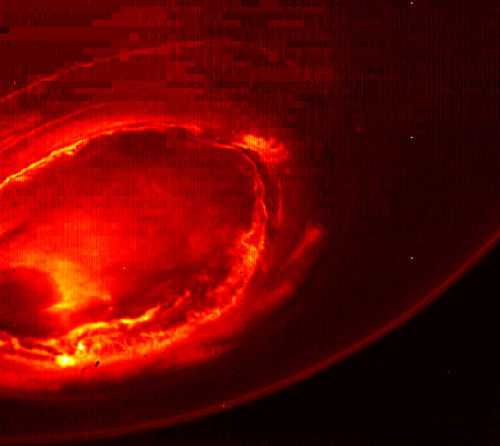

“JIRAM is getting under Jupiter’s skin, giving us our first infrared close-ups of the planet,” said Alberto Adriani, JIRAM co-investigator from Istituto di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali, Rome. “These first infrared views of Jupiter’s north and south poles are revealing warm and hot spots that have never been seen before. And while we knew that the first ever infrared views of Jupiter’s south pole could reveal the planet’s southern aurora, we were amazed to see it for the first time. No other instruments, both from Earth or space, have been able to see the southern aurora. Now, with JIRAM, we see that it appears to be very bright and well structured. The high level of detail in the images will tell us more about the aurora’s morphology and dynamics.”

Among the more unique data sets collected by Juno during its first scientific sweep by Jupiter was that acquired by the mission’s Radio/Plasma Wave Experiment (Waves), which recorded ghostly- sounding transmissions emanating from above the planet. These radio emissions from Jupiter have been known about since the 1950s but had never been analyzed from such a close vantage point.

“Jupiter is talking to us in a way only gas-giant worlds can,” said Bill Kurth, co-investigator for the Waves instrument from the University of Iowa, Iowa City. “Waves detected the signature emissions of the energetic particles that generate the massive auroras which encircle Jupiter’s north pole. These emissions are the strongest in the solar system. Now we are going to try to figure out where the electrons come from that are generating them.”

The Juno spacecraft launched on Aug. 5, 2011, from Cape Canaveral, Florida and arrived at Jupiter on July 4, 2016. JPL manages the Juno mission for the principal investigator, Scott Bolton, of Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. Juno is part of NASA’s New Frontiers Program, which is managed at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. Lockheed Martin Space Systems, Denver, built the spacecraft. Caltech in Pasadena, California, manages JPL for NASA.

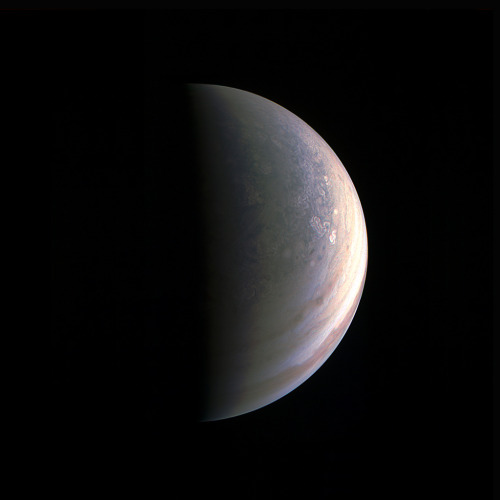

IMAGE 1….As NASA’s Juno spacecraft closed in on Jupiter for its Aug. 27, 2016 pass, its view grew sharper and fine details in the north polar region became increasingly visible. The JunoCam instrument obtained this view on August 27, about two hours before closest approach, when the spacecraft was 120,000 miles (195,000 kilometers) away from the giant planet (i.e., for Jupiter’s center). Unlike the equatorial region’s familiar structure of belts and zones, the poles are mottled with rotating storms of various sizes, similar to giant versions of terrestrial hurricanes. Jupiter’s poles have not been seen from this perspective since the Pioneer 11 spacecraft flew by the planet in 1974.

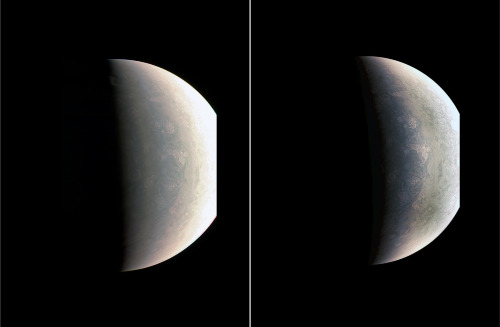

IMAGE 2….Storm systems and weather activity unlike anything encountered in the solar system are on view in these color images of Jupiter’s north polar region from NASA’s Juno spacecraft. Two versions of the image have been contrast-enhanced differently to bring out detail near the dark terminator and near the bright limb. The JunoCam instrument took the images to create this color view on August 27, when the spacecraft was about 48,000 miles (78,000 kilometers) above the polar cloud tops. A wavy boundary is visible halfway between the grayish region at left (closer to the pole and the nightside shadow) and the lighter-colored area on the right. The wavy appearance of the boundary represents a Rossby wave – a north-south meandering of a predominantly east-west flow in an atmospheric jet. This may be caused by a difference in temperature between air to the north and south of this boundary, as is often the case with such waves in Earth’s atmosphere. The polar region is filled with a variety of discrete atmospheric features. Some of these are ovals, but the larger and brighter features have a “pinwheel” shape reminiscent of the shape of terrestrial hurricanes. Tracking the motion and evolution of these features across multiple orbits will provide clues about the dynamics of the Jovian atmosphere. This image also provides the first example of cloud shadowing on Jupiter: near the top of the image, a high cloud feature is seen past the normal boundary between day and night, illuminated above the cloud deck below. While subtle color differences are visible in the image, some of these are likely the result of scattered light within the JunoCam optics. Work is ongoing to characterize these effects.

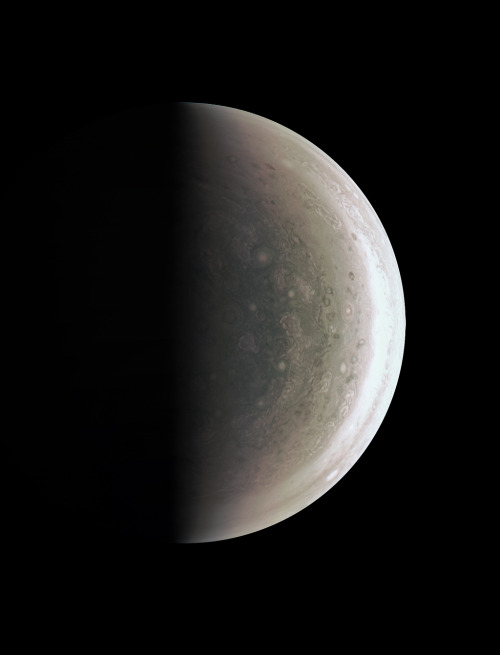

IMAGE 3….This image from NASA’s Juno spacecraft provides a never-before-seen perspective on Jupiter’s south pole. The JunoCam instrument acquired the view on August 27, 2016, when the spacecraft was about 58,700 miles (94,500 kilometers) above the polar region. At this point, the spacecraft was about an hour past its closest approach, and fine detail in the south polar region is clearly resolved. Unlike the equatorial region’s familiar structure of belts and zones, the poles are mottled by clockwise and counterclockwise rotating storms of various sizes, similar to giant versions of terrestrial hurricanes. The south pole has never been seen from this viewpoint, although the Cassini spacecraft was able to observe most of the polar region at highly oblique angles as it flew past Jupiter on its way to Saturn in 2000

IMAGE 4….This infrared image gives an unprecedented view of the southern aurora of Jupiter, as captured by NASA’s Juno spacecraft on August 27, 2016. The planet’s southern aurora can hardly be seen from Earth due to our home planet’s position in respect to Jupiter’s south pole. Juno’s unique polar orbit provides the first opportunity to observe this region of the gas-giant planet in detail. Juno’s Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) camera acquired the view at wavelengths ranging from 3.3 to 3.6 microns – the wavelengths of light emitted by excited hydrogen ions in the polar regions. The view is a mosaic of three images taken just minutes apart from each other, about four hours after the perijove pass while the spacecraft was moving away from Jupiter.

IMAGE 5….This montage of 10 JunoCam images shows Jupiter growing and shrinking in apparent size before and after NASA’s Juno spacecraft made its closest approach on August 27, 2016, at 12:50 UTC. The images are spaced about 10 hours apart, one Jupiter day, so the Great Red Spot is always in roughly the same place. The small black spots visible on the planet in some of the images are shadows of the large Galilean moons. The images in the top row were taken during the inbound leg of the orbit, beginning on August 25 at 13:15 UTC when Juno was 1.4 million miles (2.3 million kilometers) away from Jupiter, and continuing to August 27 at 04:45 UTC when the spacecraft was 430,000 miles (700,000 kilometers) away. The images in the bottom row were obtained during the outbound leg of the orbit. They begin on August 28 at 00:45 UTC when Juno was 750,000 miles (920,000 kilometers) away and continue to August 29 at 16:45 UTC when the spacecraft was 1.6 million miles (2.5 million kilometers) away.

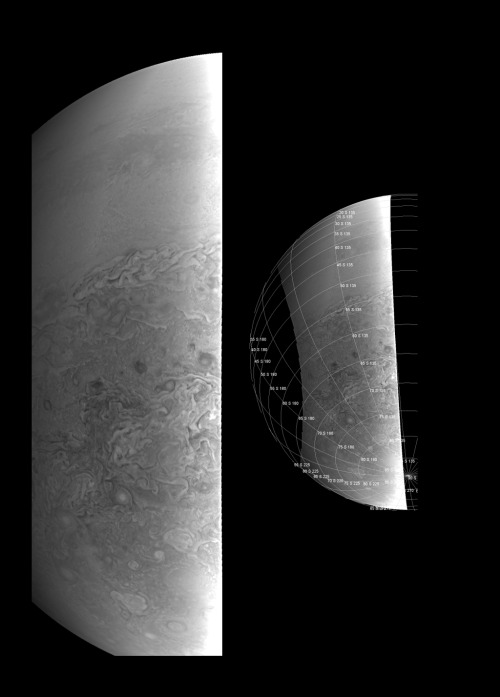

IMAGE 6….This image provides a close-up view of Jupiter’s southern hemisphere, as seen by NASA’s Juno spacecraft on August 27, 2016. The JunoCam instrument captured this image with its red spectral filter when the spacecraft was about 23,600 miles (38,000 kilometers) above the cloud tops. The image covers an area from close to the south pole to 20 degrees south of the equator, centered on a longitude at about 140 degrees west. The transition between the banded structures near the equator and the more chaotic polar region (south of about 65 degrees south latitude) can be clearly seen. The smaller version at right of this image shows the same view with a latitude/longitude grid overlaid. This image has been processed to remove shading effects near the terminator – the dividing line between day and night – caused by Juno’s orbit.

ESO 540-030

The California Nebula.

“Rho Ophiuchi Cloud Complex Area Of The Milky Way” by Martin Campbell on Flickr.

Crab Pulsar at the core of the Crab Nebula

A ‘matryoshka’ in the interstellar medium

As if it were one of the known Russian dolls, a group of astronomers, led by researchers at the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, (IAC) has found the first known case of three supernova remnants one inside the other. Using the programme BUBBLY, a method developed within the group for detecting huge expanding bubbles of gas in interstellar space, they were observing the galaxy M33 in our Local Group of galaxies and found example of a triple-bubble. The results, which were published yesterday in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, help to understand the feedback phenomenon, a fundamental process of star formation and in the dissemination of metals produced in massive stars.

The group has been building up a data base of these superbubbles with observations of a number of galaxies and, using the very high resolution 2D spectrograph, GHaFaS (Galaxy Halpha Fabry-Perot System), on the 4.2 m William Herschel Telescope (WHT) of the Isaac Newton Group of Telescopes (Roque de los Muchachos Observatory, La Palma), has been able to detect and measure these superbubbles, which range in size from a few light years to as big as a thousand light years across.

Superbubbles around large young star clusters are known to have a complex structure due to the effects of powerful stellar winds and supernova explosions of individual stars, whose separate bubbles may end up merging into a superbubble, but this is the first time that they, or any other observers, have found three concentric expanding supernova shells.

“This phenomenon -says John Beckman, one of the co-authors on the paper- allows to explore the interstellar medium in a unique way, we can measure how much matter there is in a shell, approximately a couple of hundred times the mass of the sun in each of the shells”. However, if it is known that a supernova expels only around ten times the mass of the sun, where do the second and third shells get their gas from if the first supernova sweeps up all the gas?

The answer to that must come from the surrounding gas and in the inhomogeneous interstellar medium. “It must be -says Artemi Camps Fariña, who is first author on the paper-, that the interstellar medium is not at all uniform, there must be dense clumps of gas, surrounded by space with gas at a much lower density. A supernova does not just sweep up gas, it evaporates the outsides of the clumps, leaving some dense gas behind which can make the second and the third shells”.

“The presence of the bubbles -adds Artemi- explains why star formation has been much slower than simple models of galaxy evolution predicted. These bubbles are part of a widespread feedback process in galaxy disc and if it were not for feedback, spiral galaxies would have very short lives, and our own existence would be improbable”, concludes. The idea of an inhomogeneous interstellar medium is not new, but the triple bubble gives a much clearer and quantitative view of the structure and the feedback process. The results will help theorists working on feedback to a better understanding of how this process works in all galaxy discs.

Orion Nebula And Horsehead Nebula

-

norwegianforestcat reblogged this · 3 years ago

norwegianforestcat reblogged this · 3 years ago -

humblingnothing liked this · 4 years ago

humblingnothing liked this · 4 years ago -

pentaclesandspectacles reblogged this · 5 years ago

pentaclesandspectacles reblogged this · 5 years ago -

astralangel liked this · 5 years ago

astralangel liked this · 5 years ago -

glitteringstardust reblogged this · 5 years ago

glitteringstardust reblogged this · 5 years ago -

panthera--tigris--altaica liked this · 6 years ago

panthera--tigris--altaica liked this · 6 years ago -

risaceofhearts liked this · 6 years ago

risaceofhearts liked this · 6 years ago -

dani-glz-maltes liked this · 6 years ago

dani-glz-maltes liked this · 6 years ago -

ajc18615425 liked this · 6 years ago

ajc18615425 liked this · 6 years ago -

lunacyincolour reblogged this · 6 years ago

lunacyincolour reblogged this · 6 years ago -

bowie-the-starman liked this · 6 years ago

bowie-the-starman liked this · 6 years ago -

foxboidrew liked this · 6 years ago

foxboidrew liked this · 6 years ago -

smallfryingpan liked this · 6 years ago

smallfryingpan liked this · 6 years ago -

ansiedepre liked this · 6 years ago

ansiedepre liked this · 6 years ago -

giorgioooo-blog1 liked this · 6 years ago

giorgioooo-blog1 liked this · 6 years ago -

the-chaos-goblin-child liked this · 6 years ago

the-chaos-goblin-child liked this · 6 years ago -

nogthegingerninja liked this · 6 years ago

nogthegingerninja liked this · 6 years ago -

kaleka0 liked this · 6 years ago

kaleka0 liked this · 6 years ago -

melisa-may-taylor72 liked this · 6 years ago

melisa-may-taylor72 liked this · 6 years ago -

arte-et--marte reblogged this · 7 years ago

arte-et--marte reblogged this · 7 years ago -

honeysucklemoonchild reblogged this · 7 years ago

honeysucklemoonchild reblogged this · 7 years ago -

arte-et--marte reblogged this · 7 years ago

arte-et--marte reblogged this · 7 years ago -

wild---w0rld reblogged this · 7 years ago

wild---w0rld reblogged this · 7 years ago

GREETINGS FROM EARTH! Welcome to my space blog! Let's explore the stars together!!!

144 posts