Actually Maybe Wildbow’s Tendency To Issue Poorly Thought Out Proclamations About His Stories To Win

Actually maybe Wildbow’s tendency to issue poorly thought out proclamations about his stories to win arguments with his fans is a good thing, as it forcibly introduces otherwise naive readers to the idea of the death of the author

More Posts from Khepris-worst-soldier and Others

I have to wonder what happened to Labrador when Newfoundland was destroyed. Is it still a province despite having less people than any of the Canadian territories? Was it turned into a territory? Did the Québécois irredentists win and annex it? I want to know

Cauldron’s funny in this regard, first because all of its members can fit in a minivan and because literally 90% of their capacity relies on Contessa; when she has to fake her death and can’t intervene Cauldron stops existing within a handful of hours.

And their plan is also based on the bus factor; they let the apocalypse happen early because every 2-3 months a bus crashes and every bus maybe contains the person who can kill Scion. And they are vindicated in this; Foil, Tattletale and Weaver all could have died in any of the 8+ Endbringer fights they went to, and very likely would have eventually died in one of the dozens they would have gone through if Cauldron stopped Jack from setting off Scion

This discussion of superhero logistics reminds me of an element of Worm's background worldbuilding that I've always found really interesting, which is that the heroes are running out of teleporters. They had a cloak-style mass teleporter, Strider, who was apparently indispensable for troop deployment at Endbringer fights, but he didn't get the hell out of dodge in time so by the Behemoth fight they mention having to seriously kludge other not-as-good powers to get everyone on-site on time. No one dies forever in comics so the question of "what are the risks of one guy's powers becoming indispensable to our organization" isn't as salient, but here goes Worm, gesturing at the idea that you might just get super fucking unlucky because you became organizationally dependent on a couple golden gooses who you inexplicably keep bringing to live fire situations. If they weren't hard to replace, they wouldn't exactly be superheroes, would they?

I believe you but this is insane to me because it’s explicitly a small village, the sort of place that the left is meant to view as a socially conservative backwater. That it’s not being presented negatively, by default in fixing it, is honestly kinda worrying re the state of the left

It says something that every single attempt to "fix" the cute witch in the alps game concept makes something that is vastly, vastly worse than the original idea, and sometimes is more actually fascist.

Mostly it's that the thing the Disco Elysium writers were going for is much harder than it looks from the outside. But also other things.

My correct Amy opinions

Amy is characterised primarily by the belief that she is destined for evil. She believes this because of her 'evil pedigree', a belief caused by Carol's emotional neglect, her temptations, primarily her desire for her sister, her ability to fulfill her temptations, through her power, and her lack of enjoyment of doing good through healing.

She doesn't really desire to do good; her stated reason for continuing healing is that "people wouldn’t understand if she stopped" and she never wanted to be a hero. Healing is a crushing obligation. But she doesn't want to be evil or to hurt people, and so she tries delay and deny her own evilness. Her rules exist for the sole reason to help her resist temptation.

She doesn't seek help because she believes that it wouldn't help, because of her inherent evil.

She loves her sister, and doesn't want to disappoint her.

Amy's obviously a controversial figure, and there's a lot of room for interpretation, especially once you add Ward into the picture, but I think that the above should be an uncontroversial foundation for discussing Amy, and that you're probably wrong if you disagree

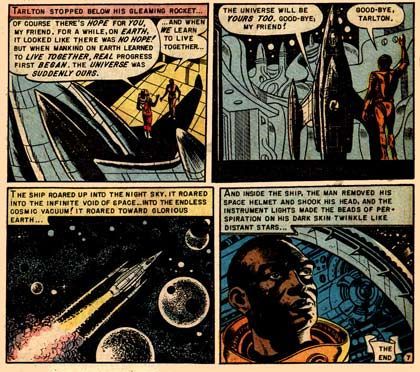

oooh have you ever done a post about the ridiculous mandatory twist endings in old sci-fi and horror comics? Like when the guy at the end would be like "I saved the Earth from Martians because I am in fact a Vensuvian who has sworn to protect our sister planet!" with no build up whatsoever.

Yeah, that is a good question - why do some scifi twist endings fail?

As a teenager obsessed with Rod Serling and the Twilight Zone, I bought every single one of Rod Serling’s guides to writing. I wanted to know what he knew.

The reason that Rod Serling’s twist endings work is because they “answer the question” that the story raised in the first place. They are connected to the very clear reason to even tell the story at all. Rod’s story structures were all about starting off with a question, the way he did in his script for Planet of the Apes (yes, Rod Serling wrote the script for Planet of the Apes, which makes sense, since it feels like a Twilight Zone episode): “is mankind inherently violent and self-destructive?” The plot of Planet of the Apes argues the point back and forth, and finally, we get an answer to the question: the Planet of the Apes was earth, after we destroyed ourselves. The reason the ending has “oomph” is because it answers the question that the story asked.

My friend and fellow Rod Serling fan Brian McDonald wrote an article about this where he explains everything beautifully. Check it out. His articles are all worth reading and he’s one of the most intelligent guys I’ve run into if you want to know how to be a better writer.

According to Rod Serling, every story has three parts: proposal, argument, and conclusion. Proposal is where you express the idea the story will go over, like, “are humans violent and self destructive?” Argument is where the characters go back and forth on this, and conclusion is where you answer the question the story raised in a definitive and clear fashion.

The reason that a lot of twist endings like those of M. Night Shyamalan’s and a lot of the 1950s horror comics fail is that they’re just a thing that happens instead of being connected to the theme of the story.

One of the most effective and memorable “final panels” in old scifi comics is EC Comics’ “Judgment Day,” where an astronaut from an enlightened earth visits a backward planet divided between orange and blue robots, where one group has more rights than the other. The point of the story is “is prejudice permanent, and will things ever get better?” And in the final panel, the astronaut from earth takes his helmet off and reveals he is a black man, answering the question the story raised.

Taylor, above anything else, has the need to be important, or at the very least not be on the sidelines.

In 25.2, when the Simurgh attacks flight BA178, Taylor is despondent because she wasn't able to go to the fight and wasn't able to help. This despite the fact that the flight went well.

And then Scion shows up and she can't do anything to him. Once again, she is sidelined. And so she invents stuff to do, so that she can be doing something and be important. Recruiting the Endbringers, attacking the Yangban and the Elite, going after Cauldron and even getting Panaceaed are all part of her running around like a headless chicken, trying not to be idle.

That this leads to the death of a thousand refugees is simply evidence of this reading; that she is not trying to help for the sake of helping, but for the sake of this need. That it is so short, and Taylor angsts so little about it, shows how far Taylor has fallen into this tendency.

At the start of Worm, she believes that she will go to hell for holding the bank hostage. At the end, she barely feels bad about killing a thousand people.

Hmm, after rereading the bit where the Undersiders and the Guild sic Leviathan on a refugee camp and kill a thousand people, I think maybe Lisa and Colin deserve everything bad that happens to them forever

I was about to make a post about the general stress of living in the world of the Power Fantasy caused indoor smoking to have a longer life, but it turns out bans on indoor smoking only really started after the turn of the millennium. They’re younger than me

Thinkin’ About Cauldron

I’m aware of the way it breaks some people’s suspension of disbelief, and I’m aware that it comes across as silly or incompetent to many, but it is deeply, deeply important to me on a thematic level that Cauldron is tiny. The tinyness is what makes them a functional foil to Taylor; you spend the whole book thinking that this is just an escalation of the problems Taylor has with Monolithic authority, and then the curtain is pulled back and you realize that the “Monolithic authority” is actually just six or seven people who are on a first name basis with each other, using their top-tier information-gathering and coordination-based powers as a force multiplier to get around their small numbers as they unilaterally seized control. (Hey, sorta like the Undersiders.)

And, furthermore, their tinyness is a stand-out example of the kind of coordination problems the book has been examining the whole time- Cauldron should be bigger, the inner circle should have more people in it, and the fact that they’ve expanded so slowly, from two to seven-ish full members, with so much of their inner circle not even having the full picture of the threat they’re up against, is deeply indicative of their wagon-circling Atlas Complex. It has to be them, they have to do it alone, or they are going to be found out and crushed.

And to be fair, they aren’t actually wrong in their assessment that they’ll be found out and crushed if they aren’t extremely careful about who they bring into the loop; overlooking the remaining entity entirely, Legend’s concern that the governments would try and coopt the power-granting process is, like. Correct. That is a thing that would happen, given the number of wormverse groups already trying to do that in some form. Siberian bit them in the ass, The Dealer bit them in the ass, and a big part of Ward is the multi-directional slapfight over the remaining Cauldron infrastructure that starts up as soon as it isn’t in a position to defend itself anymore.

There’s a real chicken-and-egg thing going on here, where it’s not clear if their paranoia is warranted given how other power players in the setting tend to behave, or if other power players in the setting behave the way they do downstream from Cauldron’s paranoia, manipulation and compartmentalization. A recurring theme with Worm is that keeping secrets and holding back resources is going to lead to terrible things happening even if keeping those secrets was a reasonable decision with the information you had available to you. You see this with Phir Se, with the Echidna fight, with the politicking over Khonsu. Cauldron is just, like, the epitome of that Morton’s Fork- be honest and open, and potentially lose everything, or, you know, be Cauldron, with all that entails.

America's modern psychic shields are Magnus's Numinous tech, which implies that they didn't have shielding prior to Magnus's rightward shift and his involvement with America. So when then, did Etienne not stop the New Mexico Festival Massacre, or at least warn Valentina? Was it a deliberate attempt to alienate her from America? Or was he even hoping that they would succeed? The balancing act would be easier with one less Superpower around, even if its Valentina, but I think they're were still too close at that point for Etienne to do that.

And more importantly, how did he explain this lapse to Valentina?

-

h4what liked this · 1 month ago

h4what liked this · 1 month ago -

catastrophic-crow reblogged this · 2 months ago

catastrophic-crow reblogged this · 2 months ago -

catastrophic-crow liked this · 2 months ago

catastrophic-crow liked this · 2 months ago -

wordless-stanza liked this · 6 months ago

wordless-stanza liked this · 6 months ago -

crunchbuttsteak liked this · 6 months ago

crunchbuttsteak liked this · 6 months ago -

zarohk reblogged this · 6 months ago

zarohk reblogged this · 6 months ago -

zarohk liked this · 6 months ago

zarohk liked this · 6 months ago -

firebatvillain liked this · 6 months ago

firebatvillain liked this · 6 months ago -

megamuscle885-blog liked this · 6 months ago

megamuscle885-blog liked this · 6 months ago -

smoothbrain13 liked this · 6 months ago

smoothbrain13 liked this · 6 months ago -

khepris-worst-soldier reblogged this · 6 months ago

khepris-worst-soldier reblogged this · 6 months ago -

scattered-storyteller liked this · 7 months ago

scattered-storyteller liked this · 7 months ago -

larky-lark liked this · 7 months ago

larky-lark liked this · 7 months ago -

changelingrain reblogged this · 7 months ago

changelingrain reblogged this · 7 months ago -

nbvagabond reblogged this · 7 months ago

nbvagabond reblogged this · 7 months ago -

meerkat-of-destiny reblogged this · 7 months ago

meerkat-of-destiny reblogged this · 7 months ago -

msevildoom liked this · 7 months ago

msevildoom liked this · 7 months ago -

saintclay reblogged this · 7 months ago

saintclay reblogged this · 7 months ago -

changelingrain liked this · 7 months ago

changelingrain liked this · 7 months ago -

mechanicsmediated liked this · 7 months ago

mechanicsmediated liked this · 7 months ago -

newholecity liked this · 7 months ago

newholecity liked this · 7 months ago -

radish-club liked this · 7 months ago

radish-club liked this · 7 months ago -

radish-club reblogged this · 7 months ago

radish-club reblogged this · 7 months ago -

glitterblossom reblogged this · 7 months ago

glitterblossom reblogged this · 7 months ago -

glitterblossom liked this · 7 months ago

glitterblossom liked this · 7 months ago -

zerphses liked this · 7 months ago

zerphses liked this · 7 months ago -

th3kidishere liked this · 7 months ago

th3kidishere liked this · 7 months ago -

haboat liked this · 7 months ago

haboat liked this · 7 months ago -

nonagon-wizard reblogged this · 7 months ago

nonagon-wizard reblogged this · 7 months ago -

droamiin liked this · 7 months ago

droamiin liked this · 7 months ago -

robotgirldisc reblogged this · 7 months ago

robotgirldisc reblogged this · 7 months ago -

robotgirldisc liked this · 7 months ago

robotgirldisc liked this · 7 months ago -

butterdudeman liked this · 7 months ago

butterdudeman liked this · 7 months ago -

toothgolem liked this · 7 months ago

toothgolem liked this · 7 months ago -

meerkat-of-destiny liked this · 7 months ago

meerkat-of-destiny liked this · 7 months ago -

spicethehamster liked this · 7 months ago

spicethehamster liked this · 7 months ago -

badbadnotgucci reblogged this · 7 months ago

badbadnotgucci reblogged this · 7 months ago -

w0lfgirl123 reblogged this · 7 months ago

w0lfgirl123 reblogged this · 7 months ago -

pinkhippo200 liked this · 7 months ago

pinkhippo200 liked this · 7 months ago -

murderthegods reblogged this · 7 months ago

murderthegods reblogged this · 7 months ago -

murderthegods liked this · 7 months ago

murderthegods liked this · 7 months ago -

scarletfasinera liked this · 7 months ago

scarletfasinera liked this · 7 months ago -

ascholarlyengineer reblogged this · 7 months ago

ascholarlyengineer reblogged this · 7 months ago -

inversemitosis liked this · 7 months ago

inversemitosis liked this · 7 months ago -

humantea liked this · 7 months ago

humantea liked this · 7 months ago -

imaencuru reblogged this · 7 months ago

imaencuru reblogged this · 7 months ago -

hugintheraven reblogged this · 7 months ago

hugintheraven reblogged this · 7 months ago -

dragongirlfangs reblogged this · 7 months ago

dragongirlfangs reblogged this · 7 months ago

Mostly a Worm (and The Power Fantasy) blog. Unironic Chicago Wards time jump defenderShe/her

165 posts