Hello Mr Gaiman, I'm Watching Dead Boy Detectives And I'm Enjoying It Very Much. But I've A Grammar Dilemma

Hello Mr Gaiman, I'm watching Dead Boy Detectives and I'm enjoying it very much. But I've a grammar dilemma about the title, since English is not my first language.

Shouldn't it be "Dead Boys Detectives" ?

Thank you!

Think of “Dead boy” as a descriptive phrase, like “tall giraffe” or “Clever Lesbian”. The Clever Lesbian Detective Agency will send clever lesbians to investigate crimes, and the tall giraffe detective agency will send tall giraffes to your house to investigate mysteries.

More Posts from Jolzr2 and Others

Happy pride month to those who are scared

Happy pride month to those who are proud

Happy pride month to those who are out

Happy pride month to those who are closeted

Happy pride month if you’re trying to figure yourself out

Happy pride month if you’ve known for years

Happy pride month to those who it’s their first

Happy pride month to those who have celebrated for years

Happy pride month to those who are afraid to celebrate

Happy pride month to those who will scream it from the rooftops

Happy pride month to you.

The Glass Closet: Taylor Swift, Chely Wright, Speculation, and the Industry That Keeps Artists in the Dark

For nearly two decades, Taylor Swift has orchestrated the art of reinvention—from a fresh-faced country prodigy to a global pop powerhouse, from America’s golden girl to a self-proclaimed anti-hero. Each era has been a transformation, each reinvention a shield. Yet, beneath the carefully curated personas, the shifting aesthetics, and the highly publicized relationships, one unspoken question lingers: Who is Taylor Swift, really?

The theory that Swift is queer and closeted—the heart of the “Gaylor” conversation—isn’t about unfounded gossip. It’s about the systems that shape an artist’s image, the forces that dictate what is and isn’t acceptable, and the very real cost of authenticity in an industry that thrives on marketability over truth.

To understand this, we have to look beyond Swift herself. We have to examine country music’s history of closeting artists like the fallout that followed Chely Wright’s coming out and the impossible balancing act Swift has performed for years.

This is a story about control, coded storytelling, and the glass closet Taylor Swift has spent her career trying to break free from—without ever shattering it completely. It's a story of paving the path for a brighter, louder, more colorful future because one thing is for sure...

SHADE NEVER MADE ANYBODY LESS GAY!

The Early Aughts + Country Music Stardom: A Foundation Built on Silence

Country music has long been one of the most traditionally conservative genres in the music industry. With a core audience rooted in Middle America values, the genre has historically upheld white, heterosexual, Christian narratives as the foundation of its storytelling.

Even in 2025, there are only a handful of openly queer country artists, and most of them struggle to receive mainstream recognition. Artists like Brandi Carlile, T.J. Osborne (Brothers Osborne), and Brandy Clark have helped pave the way, but country radio still hesitates to fully embrace LGBTQIA+ voices.

In this world, being an openly queer artist isn’t just risky—it’s career-ending.

And no one embodies that reality more than Chely Wright.

Chely Wright: A Warning from the Closet

In 2010, Chely Wright became the first mainstream country artist to come out as lesbian and it destroyed her career.

Wright was a hitmaker, with #1 songs and major industry recognition. She had everything an artist could want—until she told the truth.

Country radio blacklisted her.

Venues stopped booking her.

Her album sales tanked.

The industry that once celebrated her pretended she never existed.

Her story became a cautionary tale—a stark warning that country music does not embrace queer artists. It erases them.

By 2010, Taylor Swift was already a superstar. If she was questioning her sexuality—or even fully aware of it—she had already been placed in a carefully controlled box.

Unlike Wright, Swift’s departure from country music wasn’t an exile—it was an escape. But that escape wasn’t just about genre. It was about control. It was about building a world where she could reinvent herself while keeping parts of her identity just out of reach.

A Different Perspective: Chely Wright’s Discomfort with Speculation

When The New York Times published an essay on the Gaylor theory, I was surprised to find that Chely Wright herself expressed discomfort with the way Taylor Swift’s sexuality is discussed in public. Wright called the piece “awful” and “triggering”, criticizing the newspaper for engaging in speculation. Given that Chely’s story has long been a major point of discussion in the Gaylor community, her response was jarring. At first, it made me question whether using her experience as a lens for understanding Taylor’s career was appropriate.

But upon deeper reflection, her reaction makes sense. Chely Wright’s coming-out experience was deeply traumatic—she spent years hiding, lying, and carefully constructing a false image to survive in country music. And when she finally told the truth, her career collapsed overnight. For Wright, the mere act of publicly discussing another artist’s sexuality—whether as support or analysis—might feel like the same kind of external pressure she once faced.

However, there is an important distinction: The Gaylor conversation is not about forcing a label onto Taylor Swift. It’s about analyzing the subtext Swift has deliberately embedded in her work. If Taylor wasn’t queercoding her music, this conversation wouldn’t exist in the first place.

It’s also crucial to recognize that the industry forces that once silenced Wright are the same forces that shaped Swift’s career. While Wright may reject this discussion entirely, that doesn’t change the reality that Taylor’s work is filled with coded storytelling—suggesting she is navigating the same strict boundaries but in a different way.

Wright’s response to the op-ed highlights a larger cultural question: Why does queerness still have to be treated as a secret, while speculation about straight relationships is encouraged?

Why Is Speculating About Queerness Seen as Different?

One of the biggest criticisms of the Gaylor theory is that it’s “invasive” to speculate about Taylor Swift’s sexuality. But where is the line between analyzing queer themes in her work and being inappropriate? Why do Swifties who push back against this theory have no problem speculating about her relationships with men?

This is where the double standard comes into play.

Taylor Swift fans have spent years digging into her personal life—analyzing lyrics, finding Easter eggs, and debating which songs are about which boyfriend. Entire media cycles have been built on this:

Is "All Too Well" about Jake Gyllenhaal?

Is she secretly engaged? Was she secretly married?

Was "You Belong With Me" about Joe Jonas?

These questions are not only accepted— they're expected.

But when Gaylors apply the same level of analysis through a queer lens, suddenly, it’s labeled “invasive” and “harmful.” The message is clear: It’s only okay to speculate if the answer is straight.

To me, this is an outdated view to force straightness onto someone while also claiming that sexuality is a spectrum. Given Taylor’s layered storytelling, it feels necessary to allow her to exist on that spectrum—where maybe some of her stories are not what they seem.

As we know, Taylor Swift spent the early years of her career operating under the rigid gender norms of country music, a world where women were expected to sing about heterosexual romance, faith, family, and small-town nostalgia. But as her success grew, so did her desire for creative control—and possibly, her need to carve out a space where she could express herself more authentically, even if only in coded ways.

Her transition to pop wasn’t just about breaking genre boundaries—it was about escaping Nashville’s conservative grip and stepping into a world where reinvention, subtext, and ambiguity could thrive. And she made that clear from the very first song on 1989.

“Welcome to New York”: Taylor’s Break from Nashville & Living In Screaming Color

"You can want who you want / Boys and boys and girls and girls."

This wasn’t just a throwaway lyric. It was the loudest queer-coded statement she had ever made—and it opened the album that marked her escape from country music’s restrictions.

This is also the era that she gave us New Romantics and Out of the Woods with lyrics like, "The rest of the world was black and white but we were in screaming color."

Many Gaylors believe that Red (2012) was already a queer-coded album, with songs about a secret relationship—possibly with Dianna Agron—hidden behind PR relationships with men. But in 2014, she took it a step further:

She stopped centering men in her music.

She built a “girl squad” narrative that celebrated female friendships—but felt, at times, like something more.

She became more private—hiding her personal life while crafting an ultra-public, ultra-marketable persona.

If Red was about testing boundaries, 1989 was about reinvention as a shield. From this moment forward, Taylor would never again present her personal life without layers of control.

Reinvention as Survival: The Dual Taylors

Swift has reinvented herself with every era, but this reinvention isn’t just about artistic evolution—it’s been a survival mechanism.

She constantly presents two versions of herself—the one the public sees, and the one hidden beneath the surface.

This is the essence of the glass closet—where an artist can leave clues, drop hints, and tell the truth without ever being forced to say it outright.

Why Taylor Swift’s Closet Is Different

Unlike Chely Wright, Swift never had to lose her career over her sexuality—but that’s because she never let it become the story in the first place. The longer she hints, codes, and subtextually confesses, the veil gets thinner.

When she says “ME! out now” on Lesbian Visibility Day, people still think it’s a coincidence. When she plays "Maroon" on Karlie's birthday, it doesn't mean anything. Somehow, even when a song with such an obvious rhyme scheme as "The Very First Night" all but hits you over the head alluding to a female pronoun in a love song, Swifties turn the other cheek and deny the obvious.

She has spent 20 years writing about love—but to the general public, that love has only been for men. For those who see through the lines, she has been communicating her real experience the entire time.

Swift’s public relationships always seem to appear when speculation about her queerness reaches a peak. The Summer of Lover 2019? Joe Alwyn’s presence is reinforced. The Midnights era? Enter Matty Healy, a quick PR cycle that fizzled just as fast as it began. And now, in 2024, with The Tortured Poets Department drenched in queer themes? Travis Kelce is front and center. Whether these relationships are real, exaggerated, or entirely contractual, they always serve a purpose—to keep the glass closet from completely shattering.

The Power of Subtext in the Mainstream

In many ways, Taylor has done something radical—she’s embedded queerness into mainstream pop culture in a way that allows it to exist without being outright rejected.

Before her, queerness in the industry was often either completely hidden or presented in a hypersexualized, rebellious way that still played into the male gaze (see: Madonna and Britney’s VMAs kiss, Katy Perry’s “I Kissed a Girl”).

Taylor’s approach is different. Her queerness isn’t a spectacle—it’s woven into love songs, metaphors, and heartbreak anthems, allowing it to be as deeply felt and widely consumed as straight narratives.

For younger artists, this has cracked open the door.

Queer Artists Who Have Benefited from the Shift

Artists who emerged in the post-Taylor pop landscape now have far more room to exist as their authentic selves. Many don’t have to code their queerness the way Taylor does, and that’s partially because her queer-coding forced the industry to acknowledge that queer narratives could be commercially successful.

Examples of artists who have benefited from this shift include:

Kelsea Ballerini – A country-pop artist and close friend of Taylor Swift, Kelsea has been a vocal LGBTQIA+ ally, advocating for inclusivity in a traditionally conservative genre. While not publicly queer, her embrace of queer narratives and shift toward pop mirrors Swift’s own path, signaling a slow but growing evolution in country music.

Girl in Red – Explicitly queer in both image and lyricism, yet embraced by the same industry that would have never allowed Taylor to be this open in 2006.

MUNA – An openly queer pop band that has been able to build mainstream success without needing to obscure their identities.

Billie Eilish – After coming out as queer in 2023, Billie has embraced her identity without industry pushback, reflecting the shifting landscape Taylor helped shape. Her openness marks a new era where pop stars no longer need to rely on subtext or plausible deniability to exist authentically.

Chappell Roan – The most recent example of a queer artist who is making waves in the pop scene—heavily inspired by the theatrical elements of Taylor Swift’s songwriting and world-building.

Would any of these artists have been able to flourish in the mainstream ten years ago? Unlikely. Taylor’s massive, industry-defining career—and the queer interpretations of her work that have never been shut down entirely—helped normalize the idea that queerness doesn’t have to be a commercial risk.

The Unfinished Revolution: Taylor’s Influence on the Future of Queer Storytelling

Taylor Swift’s position in pop culture is unique—she is arguably the most famous person in the world, yet her true identity remains one of the most debated subjects in modern music.

This paradox—existing in a glass closet while simultaneously paving the way for others to live openly—is what makes her influence so undeniable.

Taylor Swift may never fully break out of the closet herself—but she has already blown the door open for others to walk through.

She has spent two decades bending the rules of the industry, proving that queer-coded storytelling is not just marketable but deeply resonant. The next generation of artists doesn’t have to bend the way she did—they can step into the spotlight and tell their stories without hiding behind mirrors and metaphors.

Taylor may be trapped in the glass closet, but the industry she reshaped will never be able to shut the door again.

LONG LIVE THE WALLS WE CRASHED THROUGH!

agatha going from:

to:

you-know-what-that-is-growth.jpg

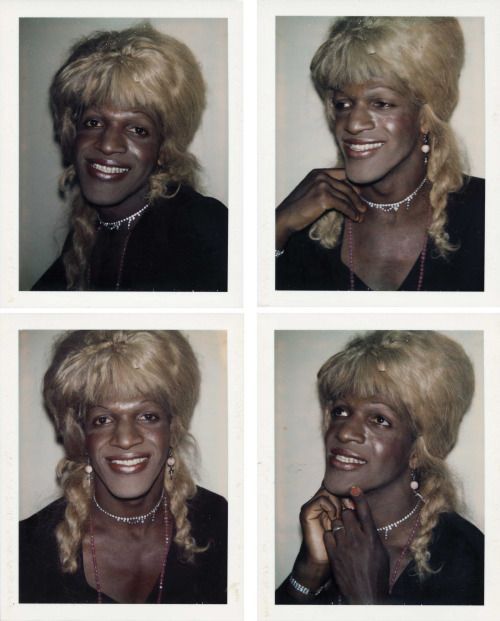

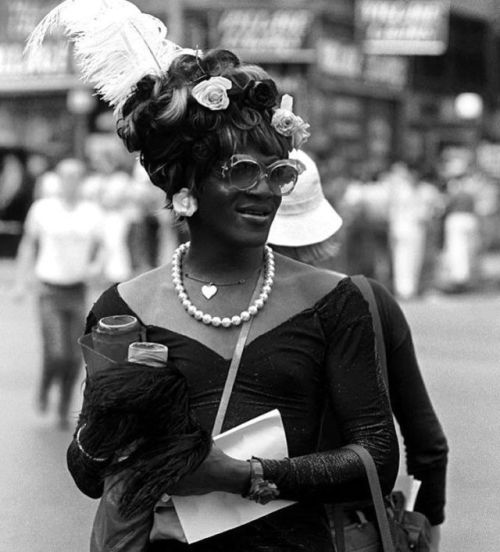

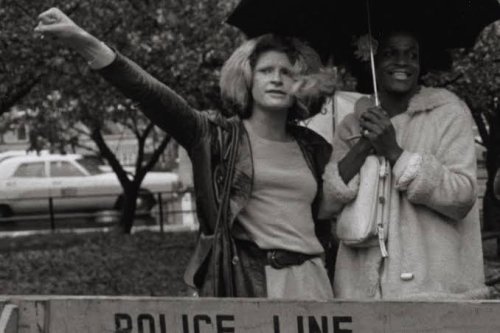

Marsha P. Johnson (August 24, 1945 – July 6, 1992) was a trans activist, sex worker, drag queen, performer and survivor. Marsha went by “Black Marsha” before settling on Marsha P. Johnson. The “P” stood for “Pay It No Mind,” which is what Marsha would say sarcastically in response to questions about her gender. In connection with sex work, Johnson claimed to have been arrested over 100 times, and was also shot once in the late-1970s. She was a prominent figure in the Stonewall uprising of 1969 and was one of the first drag queens to go to the Stonewall Inn after they began allowing women and drag queens inside. It was previously a bar for only gay men.

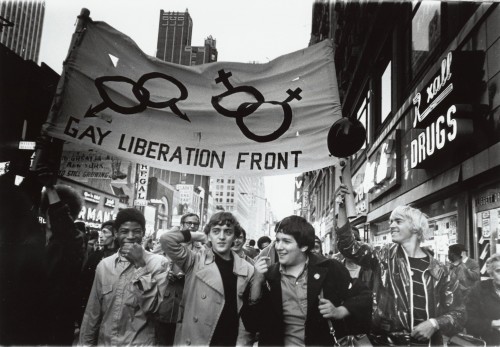

Following the Stonewall uprising, Johnson joined the Gay Liberation Front and participated in the first Christopher Street Liberation Pride rally on the first anniversary of the Stonewall rebellion in June 1970. One of Johnson’s most notable direct actions occurred in August 1970, staging a sit-in protest at Weinstein Hall at New York University alongside fellow GLF members after administrators canceled a dance when they found out was sponsored by gay organizations.

Shortly after that, along with Sylvia Rivera, she established the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) in 1970 which was a group committed to supporting transgender youth experiencing homelessness in New York City. The two of them became a visible presence at gay liberation marches and other radical political actions. In 1973, Johnson and Rivera were banned from participating in the gay pride parade by the gay and lesbian committee who were administering the event stating they “weren’t gonna allow drag queens” at their marches claiming they were “giving them a bad name”. Their response was to march defiantly ahead of the parade. During a gay rights rally at New York City Hall in the early ‘70s, a reporter asked Johnson why the group was demonstrating, Johnson shouted into the microphone, “Darling, I want my gay rights now!”

In 1974, Marsha was photographed by Andy Warhol in a series called ‘Ladies and Gentleman’ where Andy took Polaroid photos of drag queens (photos above).

Susan Stryker, an associate professor of gender and women’s studies at the University of Arizona said, “Marsha P. Johnson could be perceived as the most marginalized of people – black, queer, gender-nonconforming, poor.” Still, Stryker noted, “You might expect a person in such a position to be fragile, brutalized, beaten down. Instead, Marsha had this joie de vivre, a capacity to find joy in a world of suffering. She channeled it into political action, and did it with a kind of fierceness, grace, and whimsy, with a loopy, absurdist reaction to it all.”

Marsha’s advocacy and contributions to the LGBTQ+ community are an important part of our history and should be celebrated. Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, both key figures in the gay liberation movement, will be honored with a permanent installation in Greenwich Village which should be completed by 2021.

black lives matter and pride are intrinsically linked. the black trans community have done so much for us, we owe it to them to not forget their movement this month. without black lives, there would be no pride. black lives matter, today and always

-

we-are-fat-blob-with-electricity liked this · 5 months ago

we-are-fat-blob-with-electricity liked this · 5 months ago -

fluffy-dog8 liked this · 7 months ago

fluffy-dog8 liked this · 7 months ago -

alexthesewerrat liked this · 7 months ago

alexthesewerrat liked this · 7 months ago -

bestiebabeblog liked this · 9 months ago

bestiebabeblog liked this · 9 months ago -

stalebagelsoup liked this · 9 months ago

stalebagelsoup liked this · 9 months ago -

itsall-grey liked this · 9 months ago

itsall-grey liked this · 9 months ago -

69sillygoose69 liked this · 9 months ago

69sillygoose69 liked this · 9 months ago -

dead-tree-tattoo-artist liked this · 9 months ago

dead-tree-tattoo-artist liked this · 9 months ago -

hopeless-gay-shipper liked this · 9 months ago

hopeless-gay-shipper liked this · 9 months ago -

theghostofmidwinterpast reblogged this · 9 months ago

theghostofmidwinterpast reblogged this · 9 months ago -

aristotle0 liked this · 10 months ago

aristotle0 liked this · 10 months ago -

crumplemyletter liked this · 10 months ago

crumplemyletter liked this · 10 months ago -

sparrowchild liked this · 10 months ago

sparrowchild liked this · 10 months ago -

apickledpenny liked this · 10 months ago

apickledpenny liked this · 10 months ago -

jessyhex liked this · 10 months ago

jessyhex liked this · 10 months ago -

liar-onfire liked this · 10 months ago

liar-onfire liked this · 10 months ago -

nemmtommm liked this · 10 months ago

nemmtommm liked this · 10 months ago -

crazydiamondbeatdownnerd liked this · 10 months ago

crazydiamondbeatdownnerd liked this · 10 months ago -

i-can-get-a-wahoo liked this · 10 months ago

i-can-get-a-wahoo liked this · 10 months ago -

regulusarcturusblacklives liked this · 10 months ago

regulusarcturusblacklives liked this · 10 months ago -

eaterofworldsandsnacks reblogged this · 10 months ago

eaterofworldsandsnacks reblogged this · 10 months ago -

anxiousbookworm1 liked this · 10 months ago

anxiousbookworm1 liked this · 10 months ago -

olasde-mar liked this · 10 months ago

olasde-mar liked this · 10 months ago -

crwnoflaurels liked this · 10 months ago

crwnoflaurels liked this · 10 months ago -

cowboylikegrey liked this · 10 months ago

cowboylikegrey liked this · 10 months ago -

ladyjotei liked this · 10 months ago

ladyjotei liked this · 10 months ago -

bastardkingsir liked this · 10 months ago

bastardkingsir liked this · 10 months ago -

greelmonte liked this · 10 months ago

greelmonte liked this · 10 months ago -

notlily2 liked this · 11 months ago

notlily2 liked this · 11 months ago -

blurbsthings liked this · 11 months ago

blurbsthings liked this · 11 months ago -

ducks-water-slides-off-them liked this · 11 months ago

ducks-water-slides-off-them liked this · 11 months ago -

coralwashere liked this · 11 months ago

coralwashere liked this · 11 months ago -

lyriumrain reblogged this · 11 months ago

lyriumrain reblogged this · 11 months ago -

undertalevariations liked this · 11 months ago

undertalevariations liked this · 11 months ago -

53951683139 liked this · 11 months ago

53951683139 liked this · 11 months ago -

ourladyofthegays liked this · 11 months ago

ourladyofthegays liked this · 11 months ago -

weareallgoldensunflowersinside reblogged this · 11 months ago

weareallgoldensunflowersinside reblogged this · 11 months ago -

kkkkkkkhhhhhhh liked this · 11 months ago

kkkkkkkhhhhhhh liked this · 11 months ago -

multifandom-fanfic-writer reblogged this · 11 months ago

multifandom-fanfic-writer reblogged this · 11 months ago -

oasis-of-words liked this · 11 months ago

oasis-of-words liked this · 11 months ago -

talavenn liked this · 11 months ago

talavenn liked this · 11 months ago -

anipiece liked this · 11 months ago

anipiece liked this · 11 months ago -

i-have-no-ideas31 liked this · 11 months ago

i-have-no-ideas31 liked this · 11 months ago -

iwast3dmytim3 liked this · 11 months ago

iwast3dmytim3 liked this · 11 months ago -

vicaliciouz liked this · 11 months ago

vicaliciouz liked this · 11 months ago -

absurdist007 liked this · 11 months ago

absurdist007 liked this · 11 months ago -

brunhielda liked this · 11 months ago

brunhielda liked this · 11 months ago -

lena3333333 liked this · 11 months ago

lena3333333 liked this · 11 months ago -

cosmic-penguin liked this · 11 months ago

cosmic-penguin liked this · 11 months ago