First Loves Are Not Necessarily More Foolish Than Others; But Chances Are Certainly Against Them. Proximity

First loves are not necessarily more foolish than others; but chances are certainly against them. Proximity of time or place, a variety of accidental circumstances more than the essential merits of the object, often produce what is called first love. From poetry or romance, young people usually form their early ideas of love before they have actually felt the passion; and the image they have in their own minds of the beau ideal is cast upon the first object they afterward behold. This, if I may be allowed the expression is Cupid’s Fata Morgana. Deluded mortals are in ecstasy whilst the illusion lasts, and in despair when it vanishes.

Maria Edgeworth, Belinda (via oldtreasurechest)

More Posts from Ignorethisrandom and Others

We need another more mature adaptation, even if it’s clearly only for older kids/teens/adults with all of the details the TV series and family-friendly books choose to overlook or quietly sweep under the rug because it wasn’t family-friendly.

How Little House on the Prairie Butchered Almanzo Wilder

From Micheal Landon to Dean Butler, this list will explore everything wrong- and right- with the portrayal of Almanzo Wilder.

(In all fairness, I don’t think Butler has as much to do with this ghastly portrayal of his on-screen character as those who worked behind the scenes. He also admitted he tried his hardest to insure “the audience knew Laura would be safe with him” which came across well on screen.)

We never see his heroic act of saving De Smet

While Dean Butler saves the blind school by working two jobs, we never see Almanzo’s legendary journey to save the town. The real Almanzo Wilder and his brother Royal hoarded grain during the hard winter of 1880-1881 until Charles Ingalls, Laura’s father, confronted them about it. It was then that Almanzo and a close friend, Cap Garland, went in search of wheat to feed their starving town. They made the treacherous journey and managed to save the town, including Laura’s family.

It was a pivotal point in one of Laura’s novels, The Long Winter, and is ultimately the reason why Almanzo is deemed worthy of Laura. The audience sees him save the blind school and become seriously unwell because of that, but they never see his true defining moment.

We don’t see his second heroic act of taking Laura out of a volatile situation

In order to help support her family, Laura became a teacher. It meant she had to travel outside of her home town and board near the school. This meant she had to stay in the only homestead with enough space. The owners, the Bouchies, did not welcome her with open arms. Instead, Laura recalls Mrs Bouchie being sullen and being both aggressive towards her and Mr Bouchie. She also recalls Mrs Bouchie threatening her husband with a knife, proclaiming she wanted to go “back east”. In Laura’s books, she changes their surname to “Brewster”, but the story remains more or less the same.

To take her home each weekend, Almanzo would drive her home regardless of weather. For Laura, she was glad to leave the dangerous household, even if it meant braving Dakota blizzards.

This act of kindness continued for the entire time Laura taught at that school. She made it clear that she was only going with him to see her family, and that she did not reciprocate whatever he felt for her. He continued, and eventually she did fall for him.

He’s whinny, immature and acts like a petulant child

The real-life Almanzo Wilder was calm, persistent and reasonable. He never demanded anything of Laura, and even admired how independent she was. He never demanded anything from her, and remained patient when attempting to court her.

While we see this with Dean Butler’s portrayal in later seasons, he acts controlling and stubborn. This is particularly clear when Laura is forced to make a choice between her Pa and Almanzo, and he forces her to choose.

We never see any of his gifts to Laura

The beautiful pantry he made for her in their little house remained absent throughout the television series. Not only this, but the little slay he made for their dog to pull for Laura was also missing. He made it so she could still ride about in the snow while pregnant, which she used every day. Laura, at eighteen, would tumble of the sled into the snow, laughing and acting like the young woman she was. In fact, the one day she didn’t he became concerned at her sudden need for rest. It turned out that Laura was in labour with her first child, and he soon called the doctor.

In the adaptation we don’t get to see any of this, but why?

We don’t see their relationships for what it was

For the most part the audience doesn’t see their 19th century relationship. Almanzo peruses Laura even though she makes it clear she only goes with him on sleigh rides to get to the Bouchie school and back. He continued the strenuous journey for her benefit, proving what kind of man he really is.

We never see the exchange they have, the night he drove her home from the Bouchie’s during a deathly blizzard. He makes the trip and brings her home, keeping her awake during the trip so she doesn’t fall asleep- as Laura puts it, if you fall asleep in those temperatures, you don’t wake back up. He even later admits to being in “two minds” about it, and how Cap Garland encourages him with the line “God hates a coward.” Laura asks him if he really went to get her on a dare, yet he tells her “”No, it wasn’t a dare,” Almanzo said. “I just figured he was right.””

The audience also never sees how their first house together burned to the ground, and how Laura was terrified of his reaction - “what will Manly say to me?” The relief that he isn’t furious with her, but instead finds her on the ground and comforts her is also absent, taking the heart of the story with it.

Dean Butler’s portrayal, in the early years, would have probably left Laura at the Bouchie school and later screamed at her for burning down their house (or maybe just stormed out of town.)

We don’t see his famous pancakes

A large part of the later Little House books is Almanzo and his brother and their perfect pancakes. Sure, it’s a minor detail, but we all wanted to try them. (Where’s the recipe, Laura?)

Or his elder brother, for that matter

Royal isn’t actually a part of the television series as he only shows up twice- two different actors with three different children. He’s simply an add-on to the Ingalls-Wilder storyline.

The real Royal Wilder was a bachelor for the entirety of the book series. He was supportive of Almanzo and Laura and went as far as to care for them when they came down with Diphtheria.

Laura’s bout of diphtheria is also absent

While the television series does show Almanzo’s sickness Laura doesn’t show any symptoms. Laura, in fact, was the one who first developed symptoms and their daughter was already born. While Laura was unwell, Rose was sent to her grandparents and Almanzo cared for her until, he too, became sick. It was then that Royal came to take care of them as he was a bachelor and had no family himself.

Laura, was in fact, the sickest. She describes it as “severe” whereas Almanzo only suffered mild symptoms. She wrote, “Laura’s attack had been dangerous, while Manly’s was light.”

Almanzo’s “stroke” was also not portrayed correctly. Instead, after his illness, he went to get up one morning and found his legs could not carry him. It was mentioned that after rubbing them, circulation returned and he was able to go into town to see the doctor. He was told it was “a stroke of paralyse” and was most likely a complication of diphtheria.

Almanzo’s encouragement

Laura was often encouraged by Almanzo, even if it was unintentional. He asked her to drive Barnum, instead of telling her to “go back to the kitchen”. When Almanzo went to his parent’s farm for Christmas, he lent her Lady and the buggy so she could go for rides still. He even let her buy her own colt, and is part of the reason why she wrote the series.

We don’t see him encourage Laura to be who she is. He strikes the word “obey” from their vows, and tells her about how no decent man would keep that word in there. Laura isn’t a suffragette, but it’s a feminist moment in its own right.

Michael Landon, why turn a perfectly reasonable pioneer into a controlling husband? Sure, he’s “protective” but why make him even more backwards than an actual pioneer?

He often acted impulsively, but not selfishly

The real AJ Wilder is boyish, ambitious and adventurous. He isn’t always wise- he’s a true hero when it comes to saving the town, but at the same time he is risking his own life. He drives Laura through a deadly blizzard even against better judgement, just because he can’t see anything worse than being labelled a coward. He encourages a young woman to drive a “runaway” horse through town. He lets his heavily pregnant wife play in the snow, with a dog and sled. He drives their baby and Laura to her parents’ house during the winter because she missed them, and her family are furious that they took the risk.

Instead, we see a farmer who carries out impulsive acts differently. Almanzo’s real acts were selfless, whereas the character’s actions are nothing short selfish.

Dean Butler just didn’t look like Almanzo

Finally, the real Manly had brown hair and couldn’t have been further from Dean Butler appearance. It’s a small thing, but it is a little bothersome for die-hard fans.

The survival of Westeros is more important than the perceived race of the characters.

So I’m just sayin… they let all the Dothraki and 99% of The Unsullied die and like most of the main white people got to live.

Madeleine de Saint-Nectaire and other heroines of the French wars of religion

Between 1562 and 1598, France was torn by civil and religious conflicts between the Catholics and the Protestants. During this period, women distinguished themselves as spies, propagandists, political leaders or negotiators. Some of them even fought weapons in hand.

Agrippa d’Aubigné tells in his Universal history of Marie de Brabançon, widow of Jean de Barres, lord of Neuvy. In October 1569, the lady found herself besieged in her home by the king’s lieutenant who had 2,000 men and two cannons. She personally defended the most dangerous breach with a pike in her hand. Shamed by her example, her soldiers fought bravely. Observers recounts that they saw her defending the breach several times with her weapon. She nonetheless had to surrender in mid-November, but was allowed to walk away freely by the king’s command. Another lady noted for her military acumen was Claude de la Tour, dame de Tournon who defended her city against the protestants in 1567 and 1570. They couldn’t, however, breach her defense and had to leave.

Ordinary women also found themselves on the frontline. The city of La Rochelle was besieged between 1572 and 1573 and the townswomen fought in the defense. Brantôme tells that the besiegers saw a hundred women dressed in white appearing on the walls. Some of them performed support functions while others wielded weapons. Their bravery was confirmed by another account who tells that the women acted as “soldiers or new amazons” and that their courage led a street in La Rochelle to be called the “Ladies’ Boulevard”. Agrippa d’Aubigné similarly shows the women fighting with sword and gun. Brantôme adds that he heard that one of these women kept at home the weapon with which she fought and that she didn’t want to give it to anyone.

Another valiant lady was Madeleine de Saint-Nectaire (c.1528/30-1588) who came from a prestigious military family. She married the lord of Miremont, gave birth to three daughters, but was widowed and had to defend her lands. Agrippa d’Aubigné tells that Madeleine led a troop of 60 cavaliers against her enemy Montal, lieutenant of the king. When she fought, Madeleine charged ahead of all others, with her hair unbound in order to be recognized by both friends and foes. In 1575, Montal lured Madeleine and her troops away from the castle and planned to seize the place. The lady returned, charged at the enemy and routed their cavalry. Montal was wounded in the ensuing fight and died a few days later.

Letters written by Madeleine have been preserved and reveal another aspect of her character. They show a modest, polite woman, who cared for her husband’s illegitimate children and treated them like her own.

Bibliography:

Arnal J., “Madeleine de Saint-Nectaire”

Bulletin de la Société des lettres, sciences et arts de la Corrèze

D’Aubigné Agrippa, Histoire universelle

Lazard Madeleine, “Femmes combattantes dans l’Histoire universelle d’Agrippad’Aubigné”

Pierre Jean-Baptiste, De Courcelles Julien, Dictionnaire universel de la noblesse de France

Viennot Elianne, “Les femmes dans les « troubles » du XVIe siècle”

To give you all a visual - book!sansa was the same age as laena valaryon in hotd when she was forced to marry 30 year old tyrion, who tries going ahead with their “wedding night” and when she was being sexually harrassed and assaulted by other men at court.

Henry’s coronation was followed almost at once by his marriage. As his mother pointed out in a letter to Bellièvre, the surintendant des finances, savings would be made, notably in the distribution of gifts, by combining the king’s coronation and wedding. The marriage contract was signed on 14 February and the wedding followed next day. De Thou tells us that it was delayed till the afternoon because Henry took so long fussing over his attire and that of his bride, but royal weddings always took place then to allow time for the participants to recover from the previous previous evening’s festivities. Henry arrived at Rheims cathedral in pomp preceded by bugles and trumpets. Behind him walked the bride’s father, the count of Vaudémont. Louise’s cortège followed. Tall and blond, she wore a gown and heavy cope of mauve velvet embroidered with fleurs-de-lys. Her future brothers-in-law, the duc d’Anjou and the king of Navarre, walked on either side of her. Behind came Catherine de’ Medici and many princesses and other ladies. For once Catherine had set aside the mourning she had worn since her husband’s death in 1559. The wedding itself took place outside the cathedral’s main porch under a canopy of gold cloth. It was followed by a low mass within the cathedral celebrated by cardinal de Bourbon and the day was rounded off by a banquet and a ball at the archiepiscopal palace. According to a Venetian witness, the king and 12 princes wore suits of silver cloth adorned with pearls and jewels. The new queen, too, was superbly dressed.

Robert J. Knecht, Hero or Tyrant? Henry III, King of France, 1574-89 (pp. 105-106)

At first glance Louise de Lorraine looks like a Renaissance Cinderella story--the unappreciated young woman mistreated by her cold step-mother rescued by a handsome young king/prince--only to turn into a nightmare. Maybe that handsome king isn’t as stable as she first thought...and maybe he doesn’t really like her for herself, but because she looks a lot like his dead ex-lover who he idealizes...

How has no one written a Louise-centric novel casting her as Cinderella? The White Queen turned Elizabeth Woodville’s life into a Cinderella-gone-wrong story, it’s Louise’s turn.

History Edits: Jean Stewart, Countess of Argyll

Perhaps best known as the only sister of the infamous Mary, Queen of Scots, Jean Stewart had her own adventurous life, occupying the various roles of king’s daughter, honoured lady-in-waiting, unhappy spouse, outlaw, and excommunicant over the decades. Born in the early 1530s, she was the only certainly acknowledged* illegitimate daughter of King James V. Her mother was probably Elizabeth, a member of the sprawling, yet influential and ambitious Beaton family. On her father’s side, Jean’s numerous half-siblings included James Stewart, Commendator of St Andrews who was also the future earl of Moray and Regent of Scotland; his older half-brother and namesake James Commendator of Kelso (d.1558); John Stewart Commendator of Coldingham; and Robert Stewart, Earl of Orkney, as well as her younger half-sister, Mary Stewart, who became queen of Scots at no more than a week old upon the death of their father in 1542.

As the king’s daughter she was raised at court in considerable comfort, and the Treasurer’s Accounts record various payments for her clothing, nurse, and upbringing-including payments for gowns, a canopy for her to travel under, massbooks, and mourning clothes after the death of her grandmother Margaret Tudor in 1541. Her brothers often travelled between court and St Andrews where they were being educated, but Jean was more permanently associated with the royal court. When her father married his second wife Mary of Guise, the new queen apparently took Jean under her wing, and brought her step-daughter into her own household. Jean briefly moved to the household of her first legitimate brother Prince James, who was born in 1540, but when the infant prince died the next year she returned to the queen’s household. After 1542, when her father died and the succession of the infant Mary ushered in a new period of strife, references to Jean are less frequent. However, we at least know that when her royal sister sailed for France in 1548, Jean did not travel with her, unlike several of her brothers and at least two of her cousins, (Mary Fleming and Mary Beaton). Instead, in 1553, by which time Jean was in her early twenties, Mary of Guise and the Regent Arran arranged for her to marry Archibald Campbell, Lord Lorne, and the wedding took place in April the following year. Her new husband succeeded his father as 5th earl of Argyll five years later in 1558. By that point, both Argyll and his close friend James Stewart, Commendator of St Andrews- Jean’s half-brother- had converted to Protestantism. Though her own religious views are more of a mystery, the ideals of the new reformed faith, which was formally established in Scotland in 1560, were to play an important role in her life.

When Queen Mary returned to Scotland in 1561, she soon re-established links with her birth family, and several of Mary’s half-siblings regularly attended on her at court, though their relationships with the queen varied. The Countess of Argyll quickly renewed ties with the younger sister whom she had not seen since Mary was five years old, and though she is not as well-known as the infamous Four Maries, Jean served as one of her sister’s chief ladies-in-waiting for several years. “Ma soeur” received gifts of clothes and jewels from the queen, along with an annual pension of £150 pounds. Along with Agnes Keith (who married Jean’s brother James and became Countess of Moray in 1562) and Annabella Murray, Countess of Mar, Jean was one of the ladies Lord Darnley later blamed for causing a rift between himself and his wife. At the christening of Queen Mary’s only son, the future James VI, in June 1566, Jean and the Earl of Bedford stood proxy for Elizabeth I of England as the child’s godmother. A few months earlier, on the fateful night of 9th March 1566, Jean had been the only other woman in the room when David Rizzio was murdered, though among the men present at the dinner were her half-brother Robert Stewart and her kinsman Beaton of Creich. Jean is supposed to have caught a candelabra when the table was knocked over in the struggle, preventing the room being plunged into complete darkness. Though both her half-brother the Earl of Moray and her husband the Earl of Argyll must have been aware that there was a plot to murder Rizzio, it is unclear whether Jean was forewarned. In any case it seems unlikely that her husband would confide in her, since by 1566 the couple had been estranged for years.

Jean was a proud and determined yet often stubborn woman, and does not appear to have relished having to leave the Lowlands and court life for mountainous Argyll. Her husband was unfaithful on several occasions but does not appear to have been willing to tolerate his wife’s own infidelity, if the accusations of adultery levelled at her in the late 1550s are at all truthful. Relations steadily worsened between the couple, and Jean later alleged that, in the summer of 1560, she had been held prisoner and intimidated by several of her husband’s Campbell kinsmen. Though Jean was briefly reconciled with Argyll through the intervention of mutual friends, including the reformer John Knox, by 1563 things had deteriorated again. This time Queen Mary and John Knox made a rare collaborative effort in an attempt to reconcile the warring spouses. Mary considered Argyll a close friend and important ally and could not risk offending him, yet at the same time she was fond of her sister, and in any case their public feuding was considered an embarrassment to both the reformed faith and the royal family. While Knox gave Argyll a thorough dressing down for his infidelity and refusal to patch things up with his wife, the queen warned Jean that should she ‘behave not herself as she ought to do, she shall find no favour of me’.

In 1567, Argyll joined with many other Scottish nobles, both Catholic and Protestant, in imprisoning Queen Mary, but baulked at the idea of deposing her. He later commanded the Queen’s Men at the Battle of Langside in 1568 and subsequently became one of her chief lieutenants in Scotland after she fled to England in the same year. Meanwhile, by 1567 his marriage had completely broken down. After Jean escaped yet another bout of imprisonment in one of her husband’s retainers’ castles, refusing return to her husband, the earl finally initiated divorce proceedings. In order to settle the matter quickly, Jean was offered 10,000 merks in return for agreeing to a divorce on the grounds of her husband’s adultery. But although she certainly had no intention of reuniting with Argyll, she refused to cooperate in the divorce- whether this was due to personal morality or because she wanted to protect her status as countess is unclear. In this she was supported by her half-brother the Earl of Moray, now Regent of Scotland for the young James VI. Moray had also fallen out with Argyll over politics by this point and, though both men remained Protestant, Moray seems to have been very opposed to divorce (like Knox, who also berated Argyll for his behaviour). Moray publicly backed his sister and occasionally offered her financial support, as did other members of his extended family and Jean’s friends, like Annabella Murray (Moray’s aunt and another of Queen Mary’s former ladies-in-waiting). Frustrated over her refusal to grant him the divorce he needed, Argyll now attempted to compel his wife to return to him through the courts, but she refused to do so, leaving both spouses, the Kirk, and the political community in a bind. After Moray’s assassination in early 1570, Jean lost an important source of support from a close family member, and though her distant cousin the earl of Atholl attempted to intercede for her with Argyll, a reconciliation still never materialised. Holding out for a much more substantial settlement from her husband, whom she described as ‘that ongrait man’, Jean, took up residence with her friend Annabella Murray (Countess of Mar and James VI’s ‘Minnie’) at Stirling, with the household of the young king James. At this time she seems to have been acutely aware that she lacked a network of support, being described as ‘very angry and in great poverty’, and her situation worsened over the next few years.

In the early 1570s, the balance began to shift in favour of Argyll, who had turned to the church courts for a solution. Kirk officials repeatedly censured Jean for non-adherence to her husband: she ignored all of these warnings. When she continued to disobey the direct orders of the Kirk, she was put to the horn (outlawed), and not long afterwards, with nowhere else to turn, she took refuge in Edinburgh Castle. The castle was then undergoing the ‘Lang Siege’, with William Kirkcaldy of Grange and his men holding the castle on behalf of Queen Mary against the Regent Morton, who then governed Scotland on behalf of Mary’s son the young King James VI. This siege has gone down in Edinburgh’s history as infamous, and forever changed the shape of the castle itself. The garrison held out for three years, taking potshots at both the supporters of the young King James and the capital city at large, minting coins in Mary’s name, and housing numerous members of the Queen’s Men, including Mary’s former secretary the ‘machiavellian’ William Maitland of Lethington, as well as many other dissidents who had entered the castle for various reasons, Jean included. Though her sentence of outlawry was briefly relaxed to allow her to appear in court, Jean refused to leave the castle and was excommunicated by the Kirk in April 1573.

By this time the Earl of Argyll had finally been won over by the ‘King’s Men’ and had exchanged his allegiance to Queen Mary for a position as chancellor in the government of James VI. This enabled him to get an act of parliament passed that allowed divorce for desertion and, finally, in June 1573, Argyll legally divorced his wife. This was a landmark decision in the history of Scots law, and while Jean never accepted the divorce, her tumultuous personal life did result in the emergence of the concept of ‘divorce by desertion’ and one of the first, and certainly most famous, divorces granted by the new reformed Church of Scotland. In desperate need of an heir, her ex-husband Argyll quickly remarried, but died only three months later in September 1573, with his posthumous son by his new wife dying at birth the next year.

Only a few weeks before Jean’s divorce was announced, Edinburgh Castle had finally surrendered, having been so thoroughly bombarded by English troops that David’s Tower and the Constable’s Tower, both roughly two hundred years old, collapsed in to the main entrance of the castle. Though most of the garrison were allowed to leave freely, Kirkcaldy of Grange and his brother were hanged at the mercat cross of Edinburgh along with the jewellers who had minted the coinage in Mary’s name. Maitland of Lethington died suspiciously in prison not long afterwards, possibly by his own hand. Jean, still afraid that she would be handed over to her husband, had written to Elizabeth I of England beseeching her protection, and in the meantime crossed the water to Fife, her mother’s native county. In time though, with her husband preoccupied with his remarriage and then dying soon after, Jean actually emerged in a stronger position. For the next decade or more she harassed her brother-in-law, the new earl of Argyll (who had married the Regent Moray’s widow Agnes Keith), for a settlement which would give her financial security, claiming her right as the late earl’s widow over his ‘pretendit’ second wife. She eventually won this case, receiving a handsome pay-out which supported her to the end of her life. She seems to have spent her later years living comfortably in Edinburgh, still describing herself as the Countess of Argyll. She was legitimated by the Crown in 1580, some decades after several of her half-brothers. She lived just long enough to hear of the execution of her younger sister Mary in 1587, but her thoughts on that infamous event must remain a mystery. By this point only Jean and her half-brother Robert, Earl of Orkney remained of James V’s acknowledged children: James of Kelso had died young in 1558, John Stewart succumbed to illness in 1563, the Regent Moray was shot in 1570, and now Mary had been beheaded. In January 1588, possibly aged about 55, Jean herself died in Edinburgh, ending her dramatic career a wealthy widow. She was buried in the royal vault at the Abbey of Holyrood, next to her father King James V.

Sources below cut or, since that ‘read more’ thing isn’t showing up much, you can access them at the bottom of this page

Keep reading

I don’t really get the Jonsa/Jonerys fights because Sansa and Dany are such interesting characters to me while I find Jon so boring (that’s just my taste, nothing against people who like Jon). Why are people fighting over which of these women gets his boring ass lmao. I personally don’t like Jonerys because it feels like a boring arc for Dany - especially if she’s pregnant. And Sansa has grown so much into herself as a politically savvy ruler that it would make me sad to see her ending up as Jon’s Queen or w/ever. A lot of Jonsa fans keep comparing Jon and Sansa to Ned and Catelyn, which is fine I guess. But I don’t want Sansa to be Catelyn 2.0. I thought the whole point of the story was that they learnt to be better and smarter than their parents. Jon and Ygritte was really the only pairing that I liked for Jon, because she made up for his broodiness and made his character more relaxed and human to me. I’m not sharing my opinion just to hate on these pairings, I guess I wanted to know if there were other Sansa or Dany stans who felt this way.

Daenerys is one of the best and most complex female characters in recent literature and television history. If she does turn out to be the secret antagonist of this series (depending on whose point of view you take), I will respect the series even more for taking this huge risk you typically don’t see when it comes to female characters, especially female characters in fantasy who are usually either all good or all bad.

A really really good meta about Daenerys I found on twitter.

This is why I think Dany has always been one of my favourite characters, but I was never really sold on her actually getting the Throne once she got to Westeros, because it really revealed so much more about her motives that her storyline in Meeren sort of hid from me.

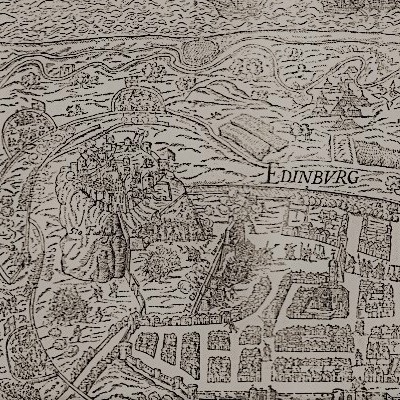

A view of Edinburgh in 1560, the year Scotland formally adopted Protestantism as the national religion.

-

oxfordsonnets liked this · 3 years ago

oxfordsonnets liked this · 3 years ago -

mars-the-menace liked this · 4 years ago

mars-the-menace liked this · 4 years ago -

ignorethisrandom reblogged this · 4 years ago

ignorethisrandom reblogged this · 4 years ago -

ignorethisrandom liked this · 4 years ago

ignorethisrandom liked this · 4 years ago -

selinezarhouquis liked this · 5 years ago

selinezarhouquis liked this · 5 years ago -

tidalwavesandquietstorms liked this · 5 years ago

tidalwavesandquietstorms liked this · 5 years ago -

letmereadinpeace4 reblogged this · 5 years ago

letmereadinpeace4 reblogged this · 5 years ago -

letmereadinpeace4 liked this · 5 years ago

letmereadinpeace4 liked this · 5 years ago -

soakinmidiamonds reblogged this · 6 years ago

soakinmidiamonds reblogged this · 6 years ago -

soakinmidiamonds liked this · 6 years ago

soakinmidiamonds liked this · 6 years ago -

wings-of-ouroboros reblogged this · 6 years ago

wings-of-ouroboros reblogged this · 6 years ago -

wings-of-ouroboros liked this · 6 years ago

wings-of-ouroboros liked this · 6 years ago -

cookiesandwhine reblogged this · 6 years ago

cookiesandwhine reblogged this · 6 years ago -

mermaidmaiden22 liked this · 6 years ago

mermaidmaiden22 liked this · 6 years ago -

aweandashes liked this · 6 years ago

aweandashes liked this · 6 years ago -

petrarchs liked this · 6 years ago

petrarchs liked this · 6 years ago -

fukiko liked this · 6 years ago

fukiko liked this · 6 years ago -

clios-purls reblogged this · 6 years ago

clios-purls reblogged this · 6 years ago -

clios-purls liked this · 6 years ago

clios-purls liked this · 6 years ago -

ellieloiso liked this · 6 years ago

ellieloiso liked this · 6 years ago -

moonlitmoth reblogged this · 6 years ago

moonlitmoth reblogged this · 6 years ago -

rozovaya liked this · 6 years ago

rozovaya liked this · 6 years ago -

floweringstars reblogged this · 6 years ago

floweringstars reblogged this · 6 years ago -

sapphoney liked this · 6 years ago

sapphoney liked this · 6 years ago -

voxpraxis liked this · 6 years ago

voxpraxis liked this · 6 years ago -

moon-light-snow-rabbit reblogged this · 6 years ago

moon-light-snow-rabbit reblogged this · 6 years ago -

moon-light-snow-rabbit liked this · 6 years ago

moon-light-snow-rabbit liked this · 6 years ago -

dreamerinthegarden liked this · 6 years ago

dreamerinthegarden liked this · 6 years ago -

crystallllines reblogged this · 6 years ago

crystallllines reblogged this · 6 years ago -

perpulchra reblogged this · 6 years ago

perpulchra reblogged this · 6 years ago -

infantisimo liked this · 6 years ago

infantisimo liked this · 6 years ago -

senatorblitz reblogged this · 6 years ago

senatorblitz reblogged this · 6 years ago -

senatorblitz liked this · 6 years ago

senatorblitz liked this · 6 years ago -

yanagibayashi reblogged this · 6 years ago

yanagibayashi reblogged this · 6 years ago -

yanagibayashi liked this · 6 years ago

yanagibayashi liked this · 6 years ago -

stephthesteph liked this · 7 years ago

stephthesteph liked this · 7 years ago -

greyseven reblogged this · 7 years ago

greyseven reblogged this · 7 years ago -

greyseven liked this · 7 years ago

greyseven liked this · 7 years ago -

sunkentreasurecove reblogged this · 7 years ago

sunkentreasurecove reblogged this · 7 years ago