Researchers Discover That Chaos Makes Carbon Materials Lighter And Stronger

Researchers discover that chaos makes carbon materials lighter and stronger

In the quest for more efficient vehicles, engineers are using harder and lower-density carbon materials, such as carbon fibers, which can be manufactured sustainably by “baking” naturally occurring soft hydrocarbons in the absence of oxygen. However, the optimal “baking” temperature for these hardened, charcoal-like carbon materials remained a mystery since the 1950s when British scientist Rosalind Franklin, who is perhaps better known for providing critical evidence of DNA’s double helix structure, discovered how the carbon atoms in sugar, coal, and similar hydrocarbons, react to temperatures approaching 3,000 degrees Celsius (5,432 degrees Fahrenheit) in oxygen-free processing. Confusion over whether disorder makes these graphite-like materials stronger, or weaker, prevented identifying the ideal “baking” temperature for more than 40 years.

Fewer, more chaotically arranged carbon atoms produce higher-strength materials, MIT researchers report in the journal Carbon. They find a tangible link between the random ordering of carbon atoms within a phenol-formaldehyde resin, which was “baked” at high temperatures, and the strength and density of the resulting graphite-like carbon material. Phenol-formaldehyde resin is a hydrocarbon commonly known as “SU-8” in the electronics industry. Additionally, by comparing the performance of the “baked” carbon material, the MIT researchers identified a “sweet spot” manufacturing temperature: 1,000 C (1,832 F).

Read more.

More Posts from Hannahhaifisch and Others

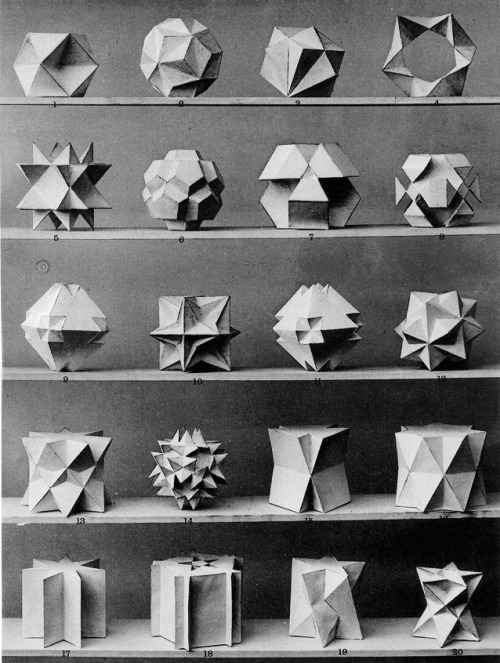

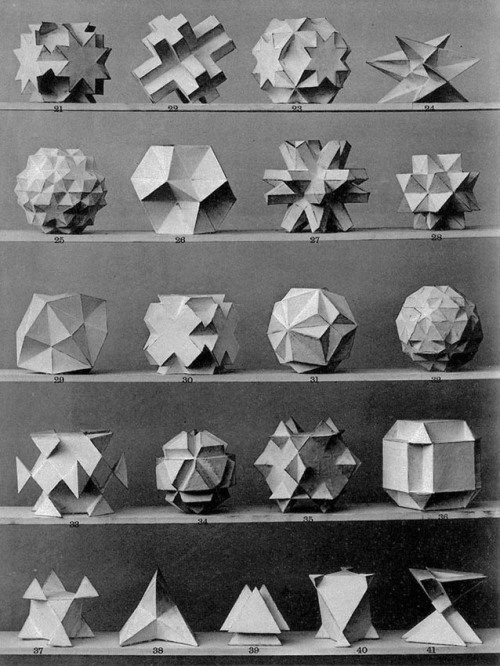

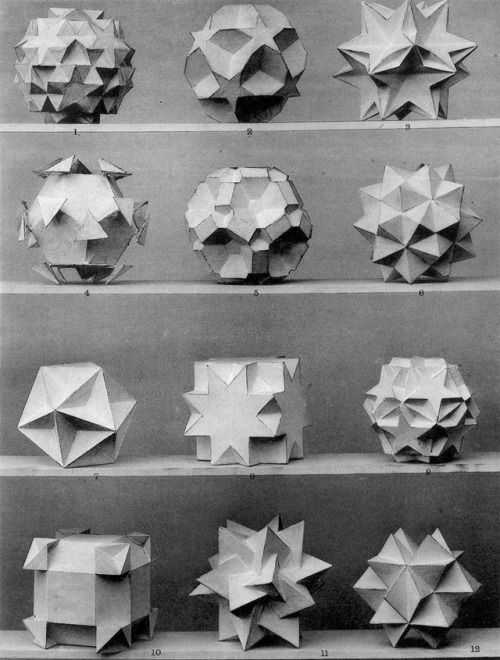

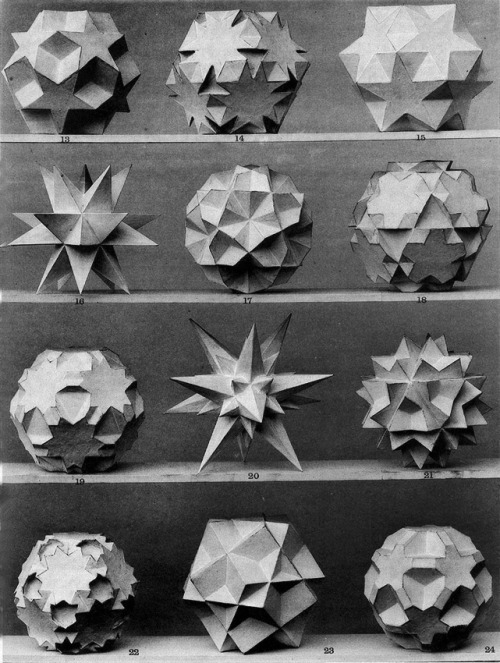

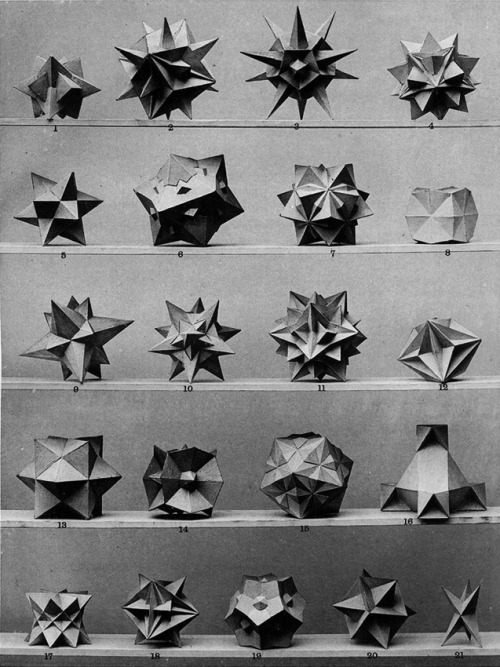

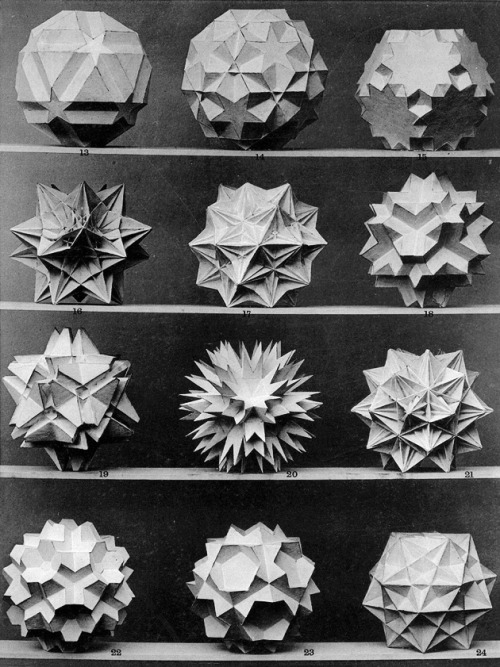

Max Brückner, from his book Vielecke und Vielfläche, 1900. Leipzig, Germany. Via Bulatov.

Brückner extended the stellation theory beyond regular forms, and identified ten stellations of the icosahedron, including the complete stellation. wiki

Glass art by Asaf Zakay.

https://player.vimeo.com/video/58293122?title=0&byline=0&portrait=0

Hannah Reber, “Untitled (spin the bottle)”, 2013, installation version #3

Where Does The Mass Of A Proton Come From?

“It is very accurately known how large the average gluon density is inside a proton. What is not known is exactly where the gluons are located inside the proton. We model the gluons as located around the three valance quarks. Then we control the amount of fluctuations represented in the model by setting how large the gluon clouds are, and how far apart they are from each other.”

If you divide the matter we know into progressively smaller and smaller components, you’d find that atomic nuclei, made of protons and neutrons, compose the overwhelming majority of the mass we understand. But if you look inside each nucleon, you find that its constituents – quarks and gluons – account for less than 0.2% of their total mass. The remaining 99.8% must come from the unique binding energy due to the strong force. To understand how that mass comes about, we need to better understand not only the average distribution of sea quarks and gluons within the proton and heavy ions, but to reveal the fluctuations in the fields and particle locations within. The key to that is deep inelastic scattering, and we’re well on our way to uncovering the cosmic truths behind the origin of matter’s mass.

Native Gold with White Quartz

Eagle’s Nest Mine, Placer County, California

0086

-

deliciouslyenchantingpenguin reblogged this · 5 years ago

deliciouslyenchantingpenguin reblogged this · 5 years ago -

deliciouslyenchantingpenguin liked this · 5 years ago

deliciouslyenchantingpenguin liked this · 5 years ago -

theverylasttimelord liked this · 7 years ago

theverylasttimelord liked this · 7 years ago -

chemist-48-blog liked this · 8 years ago

chemist-48-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

guyfromaplacecalledwolverhampton liked this · 8 years ago

guyfromaplacecalledwolverhampton liked this · 8 years ago -

daishaidar-blog liked this · 8 years ago

daishaidar-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

hannahhaifisch reblogged this · 8 years ago

hannahhaifisch reblogged this · 8 years ago -

hannahhaifisch liked this · 8 years ago

hannahhaifisch liked this · 8 years ago -

glowwpool reblogged this · 8 years ago

glowwpool reblogged this · 8 years ago -

glowwpool liked this · 8 years ago

glowwpool liked this · 8 years ago -

parzivval liked this · 8 years ago

parzivval liked this · 8 years ago -

abandonedanddead liked this · 8 years ago

abandonedanddead liked this · 8 years ago -

captain-acab reblogged this · 8 years ago

captain-acab reblogged this · 8 years ago -

the-daily-platypus reblogged this · 8 years ago

the-daily-platypus reblogged this · 8 years ago -

grimmogrimmo liked this · 8 years ago

grimmogrimmo liked this · 8 years ago -

thenanoscientist-blog reblogged this · 8 years ago

thenanoscientist-blog reblogged this · 8 years ago -

thenanoscientist-blog liked this · 8 years ago

thenanoscientist-blog liked this · 8 years ago -

iamthinking liked this · 8 years ago

iamthinking liked this · 8 years ago -

angel-no-crux liked this · 8 years ago

angel-no-crux liked this · 8 years ago -

inquirlng reblogged this · 8 years ago

inquirlng reblogged this · 8 years ago -

defroggeys liked this · 8 years ago

defroggeys liked this · 8 years ago -

higgs-boson23 liked this · 8 years ago

higgs-boson23 liked this · 8 years ago -

projection-operator liked this · 8 years ago

projection-operator liked this · 8 years ago -

redplanet44 liked this · 8 years ago

redplanet44 liked this · 8 years ago -

as-simpleaslight liked this · 8 years ago

as-simpleaslight liked this · 8 years ago -

aleplascen reblogged this · 8 years ago

aleplascen reblogged this · 8 years ago -

theejokerkiller liked this · 8 years ago

theejokerkiller liked this · 8 years ago -

ottorail liked this · 8 years ago

ottorail liked this · 8 years ago -

ginseiryu reblogged this · 8 years ago

ginseiryu reblogged this · 8 years ago -

just-call-me-shiori liked this · 8 years ago

just-call-me-shiori liked this · 8 years ago -

poets-in-a-teenage-age reblogged this · 8 years ago

poets-in-a-teenage-age reblogged this · 8 years ago -

nosetb liked this · 8 years ago

nosetb liked this · 8 years ago -

rametarin liked this · 8 years ago

rametarin liked this · 8 years ago -

knead-weed reblogged this · 8 years ago

knead-weed reblogged this · 8 years ago -

materialsscienceandengineering reblogged this · 8 years ago

materialsscienceandengineering reblogged this · 8 years ago