Two Patterns

two patterns

More Posts from Hannahhaifisch and Others

Many solids can dissolve in liquids like water, and while this is often treated as a matter of chemistry, fluid dynamics can play a role as well. As seen in this video by Beauty of Science, the dissolving candy coating of an M&M spreads outward from the candy. This is likely surface-tension-driven; as the coating dissolves, it changes the surface tension near the candy and flow starts moving away thanks to the Marangoni effect. With multiple candies dissolving near one another, these outward flows interfere and create more complex flow patterns.

These flows directly affect the dissolving process by altering flow near the candy surface, which may increase the rate of dissolution by scouring away loose coating. They can also change the concentration of dissolved coating in different areas, which then feeds back to the flow by changing the surface tension gradient. (Video and image credit: Beauty of Science)

Moss Green Halite

Locality: Sieroszowice Mine, Lower Silesia, Poland

0025

0009

Swirling swarms of bacteria offer insights on turbulence

In the bacterial world, as in the larger one, beauty can be fleeting. When swimming together with just the right amount of vigor, masses of bacterial cells produce whirling, hypnotic patterns. Too much vigor, however, and they descend into chaotic turbulence.

A team of physicists led by Rockefeller University fellow Tyler Shendruk recently detected a telling mathematical signature inscribed in that disintegration from order to chaos. Their discovery, described May 16 in Nature Communications, provides the first concrete link between turbulence in a biological system and within the larger physical world, where it is best known for buffeting planes and boats.

Amin Doostmohammadi, Tyler N. Shendruk, Kristian Thijssen, Julia M. Yeomans. Onset of meso-scale turbulence in active nematics. Nature Communications, 2017; 8: 15326 DOI: 10.1038/NCOMMS15326

When swimming together, bacteria produce swirling patterns that can disintegrate into turbulence as they speed up. Credit: Kristian Thijssen

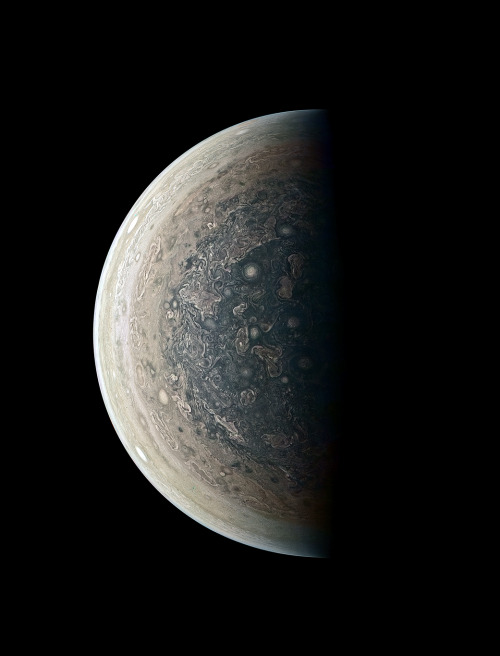

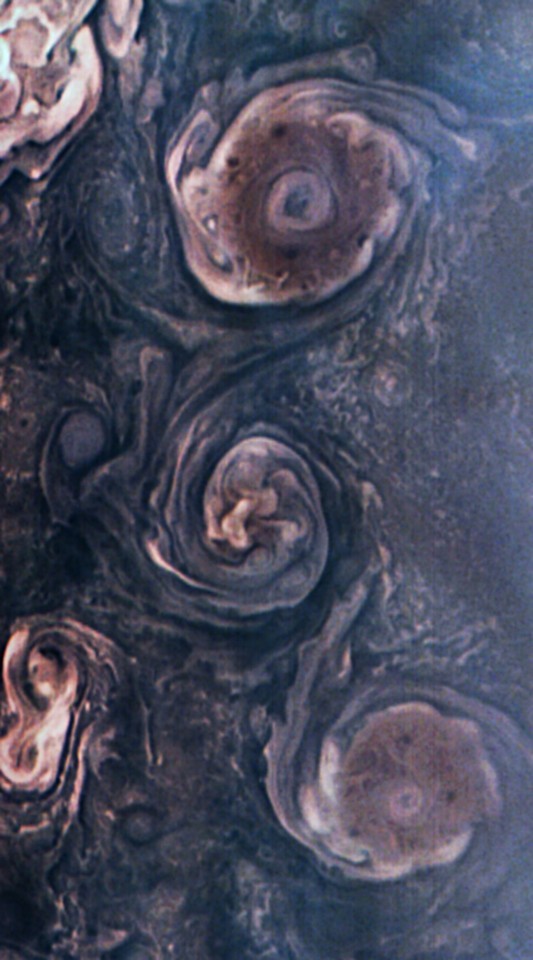

Images of Jupiter taken by JunoCam on NASA’s Juno spacecraft.

Mission Juno

Juno is a NASA spacecraft. It is exploring the planet Jupiter. Juno launched from Earth in 2011. It reached Jupiter in 2016. That was a five-year trip!

The name “Juno” comes from stories told by the Romans long ago. In the stories, Juno was the wife of Jupiter. Jupiter hid behind clouds so no one could see him causing trouble. But Juno could see through the clouds.

Juno has science tools to study Jupiter’s atmosphere. (The atmosphere is the layer of gases around a planet.) Juno will take the first pictures of Jupiter’s poles. The spacecraft will study the lights around Jupiter’s north and south poles, too.

Juno will help scientists understand how Jupiter was made. The spacecraft will help them learn how Jupiter has changed, too. The new discoveries can help us understand more about our solar system.

Sound of Jupiter’s Magnetosphere: Click here

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Mission Juno / Jason Major / Luca Fornaciari / Gerald Eichstädt

Constellation de nuit pour papa ❤️ #origami #tessellation #papa

9 years in the making, all our best geometry in one place. ❤, NakGeo

Scientists discover a 2-D magnet

Magnetic materials form the basis of technologies that play increasingly pivotal roles in our lives today, including sensing and hard-disk data storage. But as our innovative dreams conjure wishes for ever-smaller and faster devices, researchers are seeking new magnetic materials that are more compact, more efficient and can be controlled using precise, reliable methods.

A team led by the University of Washington and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has for the first time discovered magnetism in the 2-D world of monolayers, or materials that are formed by a single atomic layer. The findings, published June 8 in the journal Nature, demonstrate that magnetic properties can exist even in the 2-D realm – opening a world of potential applications.

“What we have discovered here is an isolated 2-D material with intrinsic magnetism, and the magnetism in the system is highly robust,” said Xiaodong Xu, a UW professor of physics and of materials science and engineering, and member of the UW’s Clean Energy Institute. “We envision that new information technologies may emerge based on these new 2-D magnets.”

Xu and MIT physics professor Pablo Jarillo-Herrero led the international team of scientists who proved that the material – chromium triiodide, or CrI3 – has magnetic properties in its monolayer form.

Read more.

-

veyska reblogged this · 1 year ago

veyska reblogged this · 1 year ago -

veyska liked this · 1 year ago

veyska liked this · 1 year ago -

tresfoufou liked this · 2 years ago

tresfoufou liked this · 2 years ago -

groovy-gyros liked this · 2 years ago

groovy-gyros liked this · 2 years ago -

fires-of-spring reblogged this · 2 years ago

fires-of-spring reblogged this · 2 years ago -

lovingstatesmannickellamp liked this · 2 years ago

lovingstatesmannickellamp liked this · 2 years ago -

robert50fun liked this · 3 years ago

robert50fun liked this · 3 years ago -

randomseldom liked this · 3 years ago

randomseldom liked this · 3 years ago -

mlauren86 liked this · 3 years ago

mlauren86 liked this · 3 years ago -

alcinasbloodbag liked this · 3 years ago

alcinasbloodbag liked this · 3 years ago -

thesociallyanxioussociopath liked this · 3 years ago

thesociallyanxioussociopath liked this · 3 years ago -

reggie5689 reblogged this · 3 years ago

reggie5689 reblogged this · 3 years ago -

reggie5689 liked this · 3 years ago

reggie5689 liked this · 3 years ago -

hawkebop reblogged this · 3 years ago

hawkebop reblogged this · 3 years ago -

hawkebop liked this · 3 years ago

hawkebop liked this · 3 years ago -

glass-oceans liked this · 3 years ago

glass-oceans liked this · 3 years ago -

nebulapie liked this · 3 years ago

nebulapie liked this · 3 years ago -

caltracat liked this · 3 years ago

caltracat liked this · 3 years ago -

moonwalkingcrab reblogged this · 3 years ago

moonwalkingcrab reblogged this · 3 years ago -

shadyalmondclamlover liked this · 3 years ago

shadyalmondclamlover liked this · 3 years ago -

pontanion liked this · 3 years ago

pontanion liked this · 3 years ago -

ritchie009 reblogged this · 3 years ago

ritchie009 reblogged this · 3 years ago -

hin2048 reblogged this · 3 years ago

hin2048 reblogged this · 3 years ago -

k2e4 reblogged this · 3 years ago

k2e4 reblogged this · 3 years ago -

editinspiration reblogged this · 3 years ago

editinspiration reblogged this · 3 years ago -

moonwalkingcrab liked this · 3 years ago

moonwalkingcrab liked this · 3 years ago -

graham-folger liked this · 3 years ago

graham-folger liked this · 3 years ago -

mutualweirdcalledlove liked this · 3 years ago

mutualweirdcalledlove liked this · 3 years ago -

thomasdimensor reblogged this · 3 years ago

thomasdimensor reblogged this · 3 years ago -

thomasdimensor liked this · 3 years ago

thomasdimensor liked this · 3 years ago -

alhardeee reblogged this · 3 years ago

alhardeee reblogged this · 3 years ago -

alhardeee liked this · 3 years ago

alhardeee liked this · 3 years ago -

randomarcher2013 liked this · 3 years ago

randomarcher2013 liked this · 3 years ago -

smallercommand reblogged this · 3 years ago

smallercommand reblogged this · 3 years ago -

idiotomic liked this · 3 years ago

idiotomic liked this · 3 years ago -

sunflower-cakes liked this · 3 years ago

sunflower-cakes liked this · 3 years ago -

booksniffin liked this · 3 years ago

booksniffin liked this · 3 years ago -

caught-in-the-infinite liked this · 3 years ago

caught-in-the-infinite liked this · 3 years ago -

sobeeit liked this · 3 years ago

sobeeit liked this · 3 years ago -

4tunatebutfuxedup liked this · 3 years ago

4tunatebutfuxedup liked this · 3 years ago -

1man2hands liked this · 3 years ago

1man2hands liked this · 3 years ago -

chronicbrainfag reblogged this · 3 years ago

chronicbrainfag reblogged this · 3 years ago -

jaigeyes-trampstamp reblogged this · 3 years ago

jaigeyes-trampstamp reblogged this · 3 years ago -

squeeingfangirl liked this · 3 years ago

squeeingfangirl liked this · 3 years ago