“asexuality Is Just The Lack Of A Sex Drive, Or A Really Low One” Uuhhh No. Really, No. That Is Incorrect,

“asexuality is just the lack of a sex drive, or a really low one” uuhhh no. really, no. that is incorrect, you have been lied to, i’m sorry.

asexuality is the lack of sexual attraction to anyone. sex drive is your horny meter. you can still be horny and not be sexually attracted to people! similarly you can be sexually attracted to people and not be horny!! amaze

More Posts from Enbylvania65000 and Others

I have a Twitter account devoted to Aeniith only now! Go follow me on @Aeniith_ if you’re so inclined!

Tidbits, musings, ideas, fact, and more on worldbuilding, conlangs, etc.

Last question for now: How do I get dates to show up on my posts? I don’t like everything being undated.

What’s the difference between text and chat?

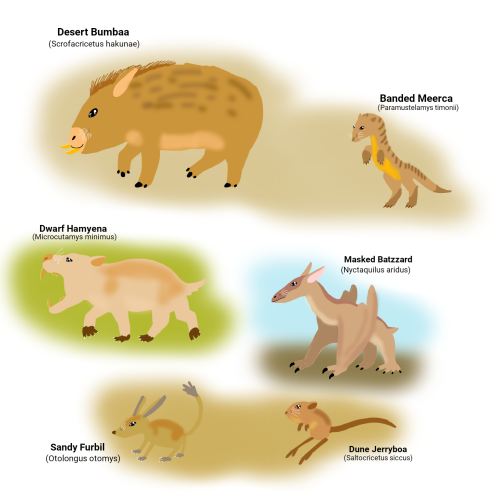

The Late Rodentocene: 20 million years post-establishment

Ain't No Passing Craze: The Great Ecatorian Desert

The continent of Ecatoria is a lush, warm tropical region, fed and nourished by rainfall from the South Ecatorian Sea. But not all of it is drizzled with a constant supply of precipitation: west of the mid-Ecatorian mountain ranges lies an expanse of land shielded from storms and moisture, and thus is dry and arid: the Great Ecatorian Desert, the largest desert on HP-02017 in the Late Rodentocene.

It is a hot afternoon in the Ecatorian Desert, and Alpha shines scorchingly overhead. On the western horizon Beta slowly begins to set, as the two suns are now separated by half a day: the coming of spring. But while elsewhere on Ecatoria spring would be mild and rainy, here in the Ecatorian Desert the climate is scorching in the day and chilling in the night: and despite this conditions some specialized organisms are able to eke out an existence in this inhospitable land.

A dark shadow glides overhead: a predatory ratbat, scouring from the skies above for any small creature down below. Though a rodent, this flying hunter is akin to a hawk, having adapted tremendously keen eyesight to home in on any movement down below on ground level. Down below, there is nothing but an expanse of sand and dry grass for miles, punctuated only by occasional towering plants, somewhat resembling cacti but in truth are highly-derived grass. Even the plants of this seeded world have begun evolving to fit new niches, not merely a green background in a planet of animals, but themselves competitors in the evolutionary race.

The ratbat-of-prey spots movement down below and circles around to zero in on its target. However, it quickly breaks off the hunt and soars off in search for another, easier meal: its rejected quarry is far too big to tackle. A desert-dwelling descendant of the cavybaras, it is nearly the size of its ancestor and simply too large for the ratbat to carry off, and so the predator wisely departs, while the lumbering beast below briefly watches the departing figure in curiosity, gives a huffing snort of confusion, and then proceeds on its way.

The creature in question is a direct descendant of the cavybaras, that has evolved modified extensions of its lower incisors that grow outward of its mouth, forming tusks which it uses in digging for food and for self-defense. Known as the desert bumbaa (Scrofacricetus hakunae), it is one of the several species of the genus Scrofacricetus, with its other cousins having adapted to different biomes, such as the forest bumbaa (S. matatai) and the plains bumbaa (S. porcius), which thrive in other regions of Ecatoria. The desert bumbaa differes from its cousins by its larger ears and thinner, sparser coat, which helps it lose heat in the arid climate.

The desert bumbaa is an omnivore, feeding mostly on tough shrubs and cacti-analogues in the desert. However, it also greatly relishes insects, many of which nest in burrows or underneath rocks and logs, and so the bumbaa puts its tusks to great use to dig up an abundance of bugs, overturning driftwood and uprooting plants to get at its prize. And its messy eating habits attract the attention of another desert dweller, the banded meerca (Paramustelamys timonii), a small, insectivorous ferrat that has developed a bizarre, and mutualistic, relationship with the bumbaa.

While fond of feasting on bugs, the desert bumbaa itself is plagued by insects of a nastier kind: wingless, bloodsucking flies that have converged with ticks and fleas as external parasites of mammalian hosts. These bugs cause the bumbaa great discomfort, but that is when the meerca comes to the rescue: an avid insectivore, it not only feeds upon the escaping leftovers of bumbaas while they raid insect nests, but also plucks the pests off the bumbaa's thick hide, offering them relief. The bumbaas have learned to tolerate and even welcome their presence, actively seeking them out and laying down to be groomed from parasites, while the meercas follow bumbaas around to be led to insect nests which the bumbaas then dig up, allowing the tiny meercas to share access to a buffet of bugs otherwise out of their reach.

Another benefit the meercas gain from the company of their lumbering companion is protection from predators: and indeed, there is a specialized predator prowling this dessicated wasteland: the dwarf hamyena (Microcutamys minimus). Smaller than many of its other relatives across Ecatoria but no less a deadly hunter, this badger-sized predator is descended from the hammibals of ten million years prior, and specializes on small rodents- including meercas. However, a full-grown bumbaa is too much for them to handle, their sharp tusks potentially being wielded with lethal force: as such, as long as the bumbaas are around, the meercas are safe from their small but fearsome enemy.

Other rodents also thrive in the Ecatorian Desert: furbils and jerryboas, ever present throughout the planet in all their diversity, exist in numerous forms throughout the desert landscape, feeding on insects, seeds and cactus-analogues, which they chew through their tough outer skin to reach the water-rich tissues inside. Their large ears and long tails act as heat sinks to lose excess heat, while their pale fur reflects heat and camouflages them in the light-colored sandy soil.

These tiny rodents, in turn, form a major part of the diet of the desert's primary aerial hunter, the masked batzzard (Nyctaquilus aridus). With a wingspan of about four feet, this desert ratbat circles the daytime sky, seeking out small prey such as jerryboas, furbils and meercas, which it swoops down onto, pounces on with its wing claws, and dispatches with a bite from its sharp, stabbing incisors. Hooked talons on its forelimbs ensure that prey is unable to easily escape, attacking its targets with an unusual hunting strike partly like a hawk, and partly like a cat. While live bumbaas are far too big to deal with, dead ones certainly aren't off the menu, and groups of batzzards may occasionally congregate at a carcass, where, due to their normally solitary lifestyle, nearly all their social interaction takes place, such as courtship, mating and dominance posturing.

Even in this harsh, dry landscape, life on HP-02017 has found a way. A wide, diverse collection of life thrives in this barren wilderness, despite its challenges --competing, coexisting, and even cooperating with one another, to overcome the harsh and unforgiving trials of life in the Great Ecatorian Desert.

▪▪▪▪▪▪▪

Technically true.

![Soca Valley, Slovenia [OC] (3456x5184) By: Peterino99](https://64.media.tumblr.com/7be6cae1a671626f7ad3ac7a60433c52/90df492e6f2866ee-b2/s640x960/c46ff64e816d75ba5819d32fae7e81a611b01794.jpg)

Soca Valley, Slovenia [OC] (3456x5184) by: peterino99

felt inspired to make this after reading some of the comments on my post about liking history

Why Gritty Why

The “Necromancy is evil“ we see in most fantasy worlds stems from a christian view of having to honor the body after death in a certain way to ensure the soul’s safety in the afterlife. And while I encourage you to explore societies that don’t see necromancy as evil, I also encourage you to explore societies that see necromancy as evil for different reasons.

Drow might believe that after death, your body belongs to Lolth and must be fed to spiders. Reanimating a body means stealing from Lolth and must therefore be punished.

A Zoroastrian inspired society might believe that with death, evil starts infesting the body, so dead bodies must be kept away from the community, and reanimating them keeps them in the community and is therefore bad.

-

harpalyketheillustrious liked this · 4 weeks ago

harpalyketheillustrious liked this · 4 weeks ago -

tenaciouskittynight liked this · 1 month ago

tenaciouskittynight liked this · 1 month ago -

billiepiperchapman liked this · 1 month ago

billiepiperchapman liked this · 1 month ago -

lost-and-cursed reblogged this · 1 month ago

lost-and-cursed reblogged this · 1 month ago -

newdawnhorizon reblogged this · 1 month ago

newdawnhorizon reblogged this · 1 month ago -

paranormal-trash liked this · 1 month ago

paranormal-trash liked this · 1 month ago -

thearchiveofthedamned liked this · 2 months ago

thearchiveofthedamned liked this · 2 months ago -

tyskak reblogged this · 2 months ago

tyskak reblogged this · 2 months ago -

tyskak liked this · 2 months ago

tyskak liked this · 2 months ago -

shirtlesspacman liked this · 2 months ago

shirtlesspacman liked this · 2 months ago -

mingmuss liked this · 2 months ago

mingmuss liked this · 2 months ago -

hireathohearth liked this · 2 months ago

hireathohearth liked this · 2 months ago -

ace-of-tales liked this · 3 months ago

ace-of-tales liked this · 3 months ago -

sinjaangels reblogged this · 3 months ago

sinjaangels reblogged this · 3 months ago -

yasmiralotta liked this · 3 months ago

yasmiralotta liked this · 3 months ago -

cordi-b-world liked this · 4 months ago

cordi-b-world liked this · 4 months ago -

treestar liked this · 4 months ago

treestar liked this · 4 months ago -

multifandom-kny-lover liked this · 4 months ago

multifandom-kny-lover liked this · 4 months ago -

alexthespaceace liked this · 4 months ago

alexthespaceace liked this · 4 months ago -

jadda23 reblogged this · 4 months ago

jadda23 reblogged this · 4 months ago -

carlyneelyisonline liked this · 4 months ago

carlyneelyisonline liked this · 4 months ago -

i-eat-rocks-truly liked this · 4 months ago

i-eat-rocks-truly liked this · 4 months ago -

capillary-collective liked this · 4 months ago

capillary-collective liked this · 4 months ago -

sunflowerblossom-0308 liked this · 4 months ago

sunflowerblossom-0308 liked this · 4 months ago -

atomicsharkchild reblogged this · 4 months ago

atomicsharkchild reblogged this · 4 months ago -

atomicsharkchild liked this · 4 months ago

atomicsharkchild liked this · 4 months ago -

fictiononthebrain liked this · 4 months ago

fictiononthebrain liked this · 4 months ago -

sanguen reblogged this · 4 months ago

sanguen reblogged this · 4 months ago -

sleepyandweepyandtired reblogged this · 4 months ago

sleepyandweepyandtired reblogged this · 4 months ago -

thehobbitbadger reblogged this · 4 months ago

thehobbitbadger reblogged this · 4 months ago -

shortandstoic reblogged this · 5 months ago

shortandstoic reblogged this · 5 months ago -

annagrzinskys reblogged this · 5 months ago

annagrzinskys reblogged this · 5 months ago -

matchestopetrol reblogged this · 5 months ago

matchestopetrol reblogged this · 5 months ago -

wildflower-war-paint reblogged this · 5 months ago

wildflower-war-paint reblogged this · 5 months ago -

clownoverrat liked this · 5 months ago

clownoverrat liked this · 5 months ago -

cripfaggot liked this · 5 months ago

cripfaggot liked this · 5 months ago -

starsiide reblogged this · 5 months ago

starsiide reblogged this · 5 months ago -

starsiide liked this · 5 months ago

starsiide liked this · 5 months ago -

crypt-teeth liked this · 5 months ago

crypt-teeth liked this · 5 months ago -

that-bug-kid liked this · 5 months ago

that-bug-kid liked this · 5 months ago -

ritesofspring reblogged this · 5 months ago

ritesofspring reblogged this · 5 months ago -

ritesofspring liked this · 5 months ago

ritesofspring liked this · 5 months ago -

wabbiteee reblogged this · 5 months ago

wabbiteee reblogged this · 5 months ago -

mapalssyrup reblogged this · 5 months ago

mapalssyrup reblogged this · 5 months ago -

mapalssyrup liked this · 5 months ago

mapalssyrup liked this · 5 months ago -

thegentlemanmoth reblogged this · 5 months ago

thegentlemanmoth reblogged this · 5 months ago -

thegentlemanmoth liked this · 5 months ago

thegentlemanmoth liked this · 5 months ago -

lloverrgiirl liked this · 5 months ago

lloverrgiirl liked this · 5 months ago -

squimpyy liked this · 5 months ago

squimpyy liked this · 5 months ago